DATE↓

STORY TYPE↓

AUTHOR↓

Peterson Rich Office deep-dives into the history of the residences’ building typology to identify problems it then seeks to fix.

Public housing in New York is, to put it politely, in a bad way. Last year, the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA)—charged with managing the city’s 177,000 government-financed apartments—racked up a startling backlog of some 584,000 incomplete maintenance requests; in 2018, the agency pegged the cost of fully refurbishing its aging building stock at a whopping $32 billion. Although recent changes in policy at the national level, such as those introduced in the Inflation Reduction Act, have helped narrow the gap somewhat, finishing the job means getting resourceful, and fast. Vicki Been, a former deputy mayor and New York University law professor specializing in land-use issues, recently outlined two routes that local political leaders are pursuing to fix the public housing crunch: “First, we have to use different federal programs to leverage private money to rehab NYCHA properties,” she said. “Second, we’ve got to find a way to use some of NYCHA’s underused land.”

Easier said than done. The challenges posed by both of those putative approaches are fantastically daunting, ranging from purely technical questions of design and construction, to the more abstract (and thornier) political problem of building on public property where thousands of people already live. Overcoming those issues requires a keen sensitivity for the concerns of existing public housing tenants, a working knowledge of legalese, and a broad and compelling architectural vision. Few people in the design and planning field can claim even one of these. As it happens, Miriam Peterson and Nathan Rich, the married principals of the New York–based Peterson Rich Office (PRO), have all three.

“We started working on [our proposals for NYCHA] in the first couple months after we formed our office,” says Peterson. In 2012, after nearly a decade with some of the most distinguished firms in the United States (including Peterson’s work with Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects, and Rich’s stints with Steven Holl and SHoP Architects), the couple decided to strike out on their own, setting up shop in southern Brooklyn under the PRO banner with the aim of creating a distinct kind of practice: socially driven, community-focused, and diverse both in what it looks to do as well as how it does it. Since then, with its remarkably international team of associates, hailing from six countries and speaking five languages, the firm has worked on projects ranging from art museums to private penthouses—alongside its ongoing partnership with the country’s biggest public housing program, for which they provide vital insights and suggestions for improvement.

The latter effort helped put PRO on the map and underscored its style. “They create these beautiful design solutions,” says Andrew Bernheimer, a fellow architect who first became aware of the firm after its initial public housing investigation attracted a burst of professional and media attention. “Each one is rooted in really deep research, discovery, and opportunity.”

And while the firm’s ever-refined ideas for NYCHA remain in the proposal phase, that hasn’t stopped the practice from turning heads. Following PRO’s early foray into the subject, the architects were asked to elaborate on their proposition in an in-depth Regional Plan Association (RPA) report, released in August 2020, focusing specifically on the Cooper Park Houses project in the East Williamsburg area of Brooklyn; that proposal caught the eye of the Museum of Modern Art, which will include images and a large-scale model from an updated version of the Cooper design in the upcoming exhibition “Architecture Now: New York, New Publics,” opening February 19. The debut represents an important potential turning point—both for the architects behind it, and for the affordable housing they’ve spent a decade trying to transform.

The key to PRO’s inventive designs for the housing authority stems from the firm’s decision to look to history to figure out the origin of its woes. The idea of engaging with NYCHA, and with the whole vexed question of public housing in New York, originally came to PRO by way of an invitation from the Institute for Public Architecture (IPA), a local nonprofit specializing in urbanism and civic-minded design. In this instance, the group was canvassing for responses to then Mayor Bill de Blasio’s recent challenge to ramp up affordable housing preservation and construction in the city. “While NYCHA is mentioned throughout the document, specific and actionable recommendations for NYCHA are not made, and the plan does not recognize the scale or immediacy of NYCHA’s problems,” says Peterson. “We found that to be such a gross omission.”

To counteract it, the architects set about using their fellowship to launch an intensive research project, looking at NYCHA facilities citywide. “It started with an idea about parking specifically,” says Rich. As anyone who’s ever walked past a New York housing project can attest, NYCHA’s red-brick apartment high-rises are surrounded by vast stretches of barren asphalt, often with no actual cars in sight. In a metropolis with some of the best public transit in the world, the waste of space is fairly galling, and it prompted PRO’s initial scheme: entitled 9x18, the IPA-funded design envisioned a series of new buildings to be erected on NYCHA parking lots, using the titular module as a starting point.

But as the architects shortly recognized, cars were only one part of a broader problem. “It’s the same replicable type all around the city,” says Rich. “The old tower-in-a-park model. We thought if we could figure out a response to that general condition, we could get traction everywhere.” More than just the parking spaces, the architects began to look at all of the vacant land surrounding NYCHA’s properties throughout the five boroughs, leading to their more elaborate Scalable Design Solutions proposal for the RPA.

For that initiative, the firm took on the entire legacy of city planning, beginning in the years immediately before the Second World War. When the federal government began its major push into affordable housing construction (NYCHA itself was founded in 1935), the prevailing urbanist orthodoxy held that the density of American cities—the row on row of tenement houses crowded around traffic-clogged streets—were their primary and fatal failing. Taking a page from European social housing of the 1930s (influenced, in turn, by pioneering Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, who helped touch off the Modernist movement with his schemes for massive high-rises surrounded by grassy lawns), PRO found that early federal legislation stipulated specific maximums for lot coverage: as low as 35 percent in the 1940s, with most authorities preferring to go still lower, reserving the rest of the land for recreation and open space.

Appealing in theory, the application of the towers-in-a-park typology to American public housing proved to be seriously flawed, especially as realized by New York’s infamous master planner Robert Moses, who oversaw much of the city’s postwar housing construction. “Like Le Corbusier,” observed critic Lewis Mumford in the late ’40s, “Moses confused visual open space with functional, habitable open space.” Instead of lively places for rest and recreation, many of NYCHA’s open spaces turned out as sterile and unwelcoming as the parking spaces that now sit alongside them.

So if New York’s public housing needs new investment—and if a huge chunk of the real estate owned by NYCHA doesn’t have any structures on it—why not just invite private developers to build on the available land, and then plow the earnings back into the agency’s buildings? Well, a lot of reasons, as PRO discovered. For one thing, says Peterson, “Habitable spaces in NYC need to have sixty feet of space from window to window,” a legal requirement that substantially reduces the buildable space on agency campuses. Moreover, until relatively recently, public housing authorities nationwide were tightly constrained in how much of a toehold they could give the private sector on government-owned land; though the rules began to loosen over the last decade, the agency still won’t build willy-nilly on any vacant parcel in their portfolio. “Their policy is that residents have to have a say in any new construction,” says Peterson. Whatever PRO proposed to do for NYCHA, they knew it would have to be something NYCHA’s tenantry could live with.

What Rich and Peterson came up with threads the needle between what those half-million public housing residents want, and what the city at large needs. “It became a plan that was about integrating renovation with extension,” says Rich. Rather than building new towers alongside the old, the architects proposed renovating the existing buildings while adding a series of low-rise structures around them, stretching into the underutilized territory on all sides. Never rising above the fourth floor, the additions would meet the towers at oblique angles—“kissing at the corners,” as Rich puts it—thereby ensuring access to light, air, and views for every unit. With continuous ground-floor flow between the tower lobbies and the new extensions, the entire base level of the expanded complexes could host a new suite of amenities, from bike storage to fitness centers and beyond. Even more promising, the architects realized that the towers themselves were so robustly constructed that they could accommodate additional floors on top of them. “You can extend these buildings both horizontally and vertically,” says Rich.

As a first act for a newly launched architecture practice, PRO’s bid to solve the NYCHA puzzle was nothing if not ambitious. But aiming high appears to have paid off. “Restoring NYCHA to a state of good repair is a baseline,” says Moses Gates, vice president for Housing and Neighborhood Planning at the RPA. “This plan goes beyond this, and adds new amenities for NYCHA tenants—and does it in a way that saves NYCHA money.”

What’s more, PRO has taken some of the lessons learned from their public housing investigations and put them to immediate good use: In a pair of upcoming projects—transforming a decommissioned church in Detroit into a new arts and community space, and adding an addition to Wesleyan University’s Davison Art Center—the architects are following a similar adaptive-reuse playbook, making the most of historic structures while looking to the future of the communities who use them.

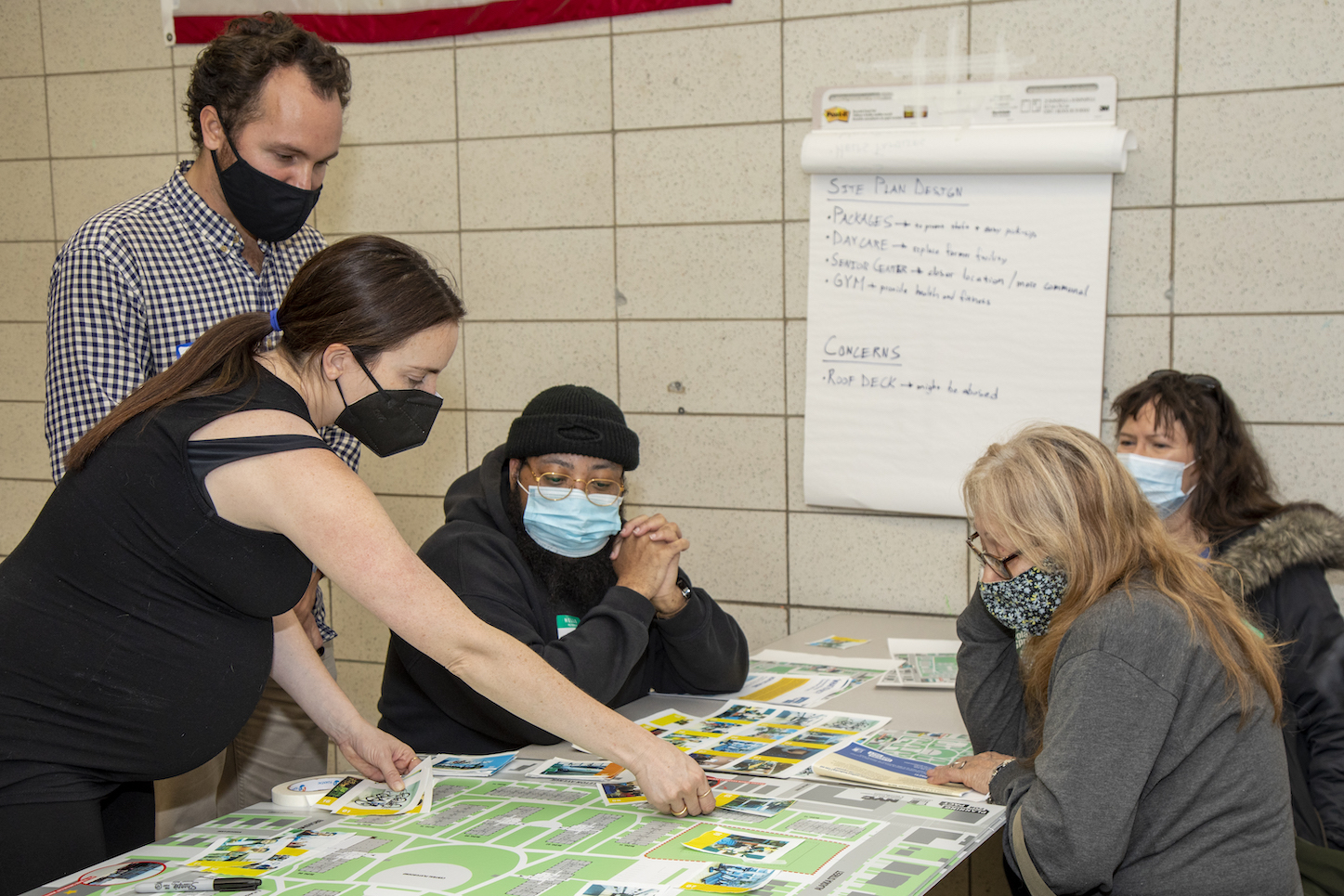

The question, however, remains: What will the NYCHA community think of PRO’s radical ideas to reinvent their homes, and will residents like them enough to make those ideas a reality? In spite of working with an agency (and in a profession) that is notoriously slow, the architects already have at least a tentative answer to those questions, acquired by taking matters into their own hands. From the very start, the duo has made talking to NYCHA residents a top priority. “We’ve done four community sessions already,” says Rich, and the response thus far has been remarkably encouraging. The potential for a real and positive impact—the influx of new funds for repairs, as well as new low-cost housing next door—has given PRO’s speculative-yet-pragmatic solution at least a fighting chance to move beyond the boards.

NYCHA continues to fund the architects’ research, and the couple seems optimistic that the MoMA show will help make more converts and accelerate support for its project, showing what’s possible if New Yorkers dare to dream. “We want [our proposals] to have a legibility and communicability that people can connect with,” says Peterson. “Those are the goals we always have at heart.”