DATE↓

STORY TYPE↓

AUTHOR↓

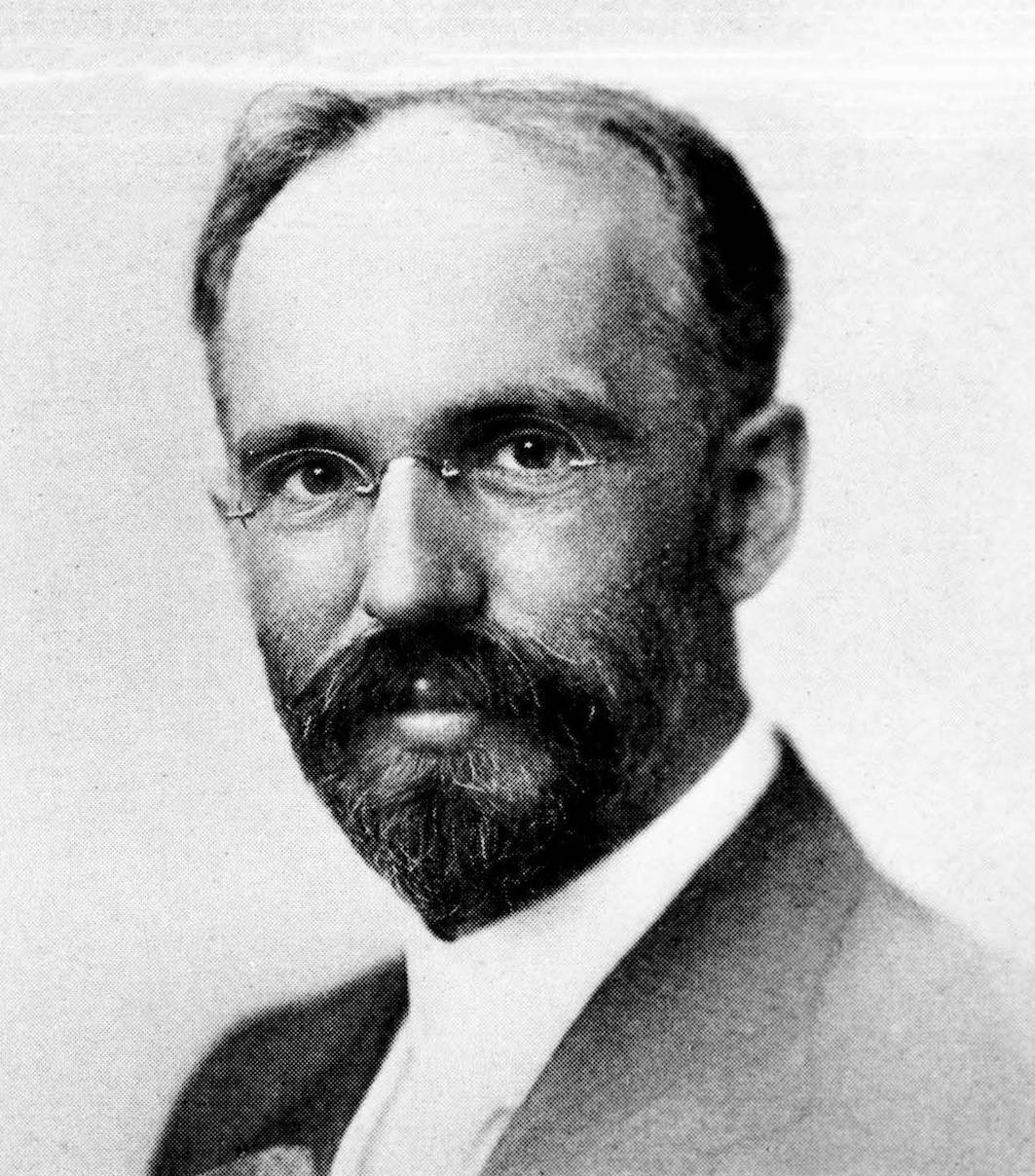

Dwight H. Perkins designed Chicago public schools as neighborhood centers in the early 1900s. Many still serve their communities today.

There is a lesser-known shadow twin to Daniel Burnham’s epic 1909 Plan of Chicago, which synthesized many elements of contemporary urbanism we have come to expect from cities: comprehensive parks and highway systems, an orderly street grid, preserving the city’s waterfront as a public amenity, and coherent neighborhood-scaled civic centers. Burhamn’s plan was a top-down vision of what city life could look like, and resides in our collective memory as perhaps the American sepia-toned path to refined and humane urban planning.

However…. A 1905 plan by architect Dwight H. Perkins saw the city radically differently, but was perhaps just as influential.

His plan peered beneath the illusory façade Burnham depicted with monumental boulevards and Classical, European airs into the violent, impoverished, and desperate reality of the streets. Perkins, a Progressive-Era reformer who spent formative portions of his career working with Burnham, instead illustrated the city with data on its lived conditions. Steeped in populist zeal with compatriot Jane Addams and the settlement house movement, Perkins saw Chicago through the lens of sociology and demographics, not through its urban form. He overlaid statistics on population density, crime, disease transmission, and more onto the map. There are no images of architecture.

Perkins’s metropolitan plan reimagined the city as “a terrain for sociological investigation and political activism,” according to a 2014 article in the journal AMPS (Architecture, Media, Politics, Society) by Jennifer Gray, who may be the foremost scholar on Perkins’s wildly understudied historical legacy. He would later use architecture—schools, in particular—to facilitate this activism. Curiously, what these schools looked like hardly concerned him. But from his study of the city and his time as a child near the South Side, raised by a single mom and wading through the butchery and offal of the stockyards that he quit school to work for after eighth grade, he knew exactly what they needed to do.

Perkins described schools as “the bulwark of democratic social organization.” In 1915, he wrote in the pages of The Brickbuilder, “The school, by its relation to all of the people, regardless of the divisions of politics, religion, or wealth, is the only institution which can be made to serve as a neighborhood or social center.” This sentiment, divorced from any agenda toward formal or stylistic gesticulation, managed to generate numerous schools across the city that are still operating and beloved today. Their longevity owes little to how they look, and a lot to their flexibility and the ways they’ve been able to serve diverse populations over the years.

The city Perkins confronted had been corporatized in ways that were disturbing and deleterious. It was organizing the material resources of the center of North America into an industrial maw at the southern tip of Lake Michigan that ground cheap immigrant labor into the finished goods, and thus market command, that would help claim total American hegemony in the decades ahead.

“The pains of capitalist transformation had thrown into stark relief the depths of human misery that accompanied it: unspeakable housing conditions, contaminated food and water supplies, violent social conflict, labor exploitation, abject poverty, and so on,” Gray writes in her 2011 dissertation on Perkins, a powerful exploration of the role of a designer and advocate during an era where the modern conception of the public realm was still in formation. She notes that Perkins “argued that strategically placed, small-scale interventions would ameliorate the devastating impact that unplanned growth had on the urban poor, and that those spaces would advance democratic social ideals in a city highly segregated by race, ethnicity, and wealth.”

For an architect born a few years after the Civil War, that’s wildly modern framing. As presented by Gray, Perkins was perhaps the first American architect to challenge the framework of the laissez-faire metropolis as a designer-activist.

From 1905 to 1910, Perkins was the school board–designated architect for the city’s public schools. He designed more than 40 of them during this short span, around the time Chicago hit its stride as one of the fastest growing cities in the world. Directing a staff of 250, he replicated building templates with as little change from site to site as possible. Work was organized into a sort of drafting-table mass production.

In the archive stacks of the Chicago History Museum, Perkins’s correspondence is all about fireproofing schedules and window ratios. There is a six-page letter to the president of the school board about ventilation. Perkins gave lectures not on school aesthetics, but on lighting. He was a public architect working within narrow budgets and accustomed to compromise.

But buildings have to look like something, and Perkins’s turned out pretty well. They tend toward simple, abstract geometric detail without historicist flourishes, and draw texture and richness from simple materials, mainly brick and terra-cotta. They are very much transitional architecture, built at a time when the aesthetic range of acceptable styles was at a historically wide aperture, but executed in accordance with proto-Modern Chicago School formal and material honesty. Few preen or demand attention, and a quick drive-by signals not much more than “local civic building.” In a 1909 speech to the National Education Association about the schools, Perkins told his audience that “all parts—the plan and the exterior design—should be direct, straightforward, and simple.” But, he added, there was nothing wrong with charm … “if possible.”

Perkins’s Chicago schools became more utilitarian (and perhaps more Modern, to contemporary eyes) and less stylized over time, which was perhaps the result of budget fights with corrupt board of education leadership. Earlier schools featured hipped, gabled roofs supported by copper-clad brackets. Later schools are stolid prize-fighters, flat-roofed and boxy with only subtle brickwork to differentiate them from the factories their students were bound for without more comprehensive education. Perkins’s son, Lawrence Perkins, would fully embrace Modernism and go on to found mega-firm Perkins&Will, with an early specialty in education architecture. Lawrence’s buildings brought his father’s ethos into this new formal and material language, deploying midcentury cutting-edge steel-and-glass schools for the residents of the city’s most impoverished and isolated public housing developments.

Programming was how Dwight Perkins made his schools vital. Before him, the first generation of Chicago public schools were designed as a stack of undifferentiated classrooms piled around a central staircase. Desks were bolted to the floor in rows with the teacher placed behind a raised desk, drilling students with hundreds of questions per class period. As factories for memorization and recitation, “school architecture” didn’t really exist. There were so few spatial performance requirements that a typology couldn’t form.

And there was little demand. Only a tiny percentage of American public school students went to high school in 1880. But progressive child labor laws and an understanding of adolescence as a distinct period of developmental growth quickly forced a much wider population into this strangely intimate interaction with the state, generating vast demand for education infrastructure. Given the exploitation experienced by the immigrant masses that teemed into Chicago (and also their predilection for sectarian cultural boundaries, which was viewed with suspicion), reformers urged districts to see educating not just children, but the entire community, as their responsibility—and to use schools to do it.

So Perkins’s schools were designed with a broad range of classroom spaces. There were massive manual training wings (machine shops, forges, carpentry), as well as art and print-making studios, test kitchens, and gardens for the study of biology and botany. Perkins saw schools as the front lines of the struggle for public health, insisting on playgrounds for physical activity, natural light to aid eyesight, fireproofing, and more.

The next step was to “throw away the keys to the front door,” as Perkins wrote in The Brickbuilder, designing all these offerings to be accessed by the entire community. As such, he would often favor village-like plans for large schools that would allow each of these distinct functions to be locked and opened independently for the wider population. Very often, a big auditorium would be located directly across from the main entrance to make it publicly accessible; this “fulcrum on which the entire school turned” (as Gray described it in her dissertation) was to be the neighborhood’s civic heart.

These social centers are evolutions of the traditional New England town hall, translating the outdated 19th-century democratic ideal into sectarian and unruly Chicago, which was more than 77 percent foreign-born in 1900. For progressives like Perkins and Addams, omnipresent neighborhood social centers—all-purpose spaces for social services, education, and organization—were required to address the needs of atomized immigrant communities largely divorced from the power structures that could make city life bearable.

As mature finance capital attracted workers from farther-flung regions of the globe and pressed them into new labor divisions in urban centers, this social stratification calcified, and access to the broader trough of American prosperity became illusory. The relatively homogenous White Protestant Concerned Citizens League making a petition on the Towne Greene back East had a common language, heritage, and culture with the power elite that governed them, but the situation was different in the Polish or Ukrainian quarters of Chicago, to say nothing of the South Side Black Belt or Chinatown.

As such, each of these communities needed their own civic spaces in which to build intersectional solidarity and synthesize demands. These social centers were both places to advocate for and to receive cultural and class-specific concessions as well as egalitarian forums, where people of different classes and ethnicities could form the social bonds required for representative democracy.

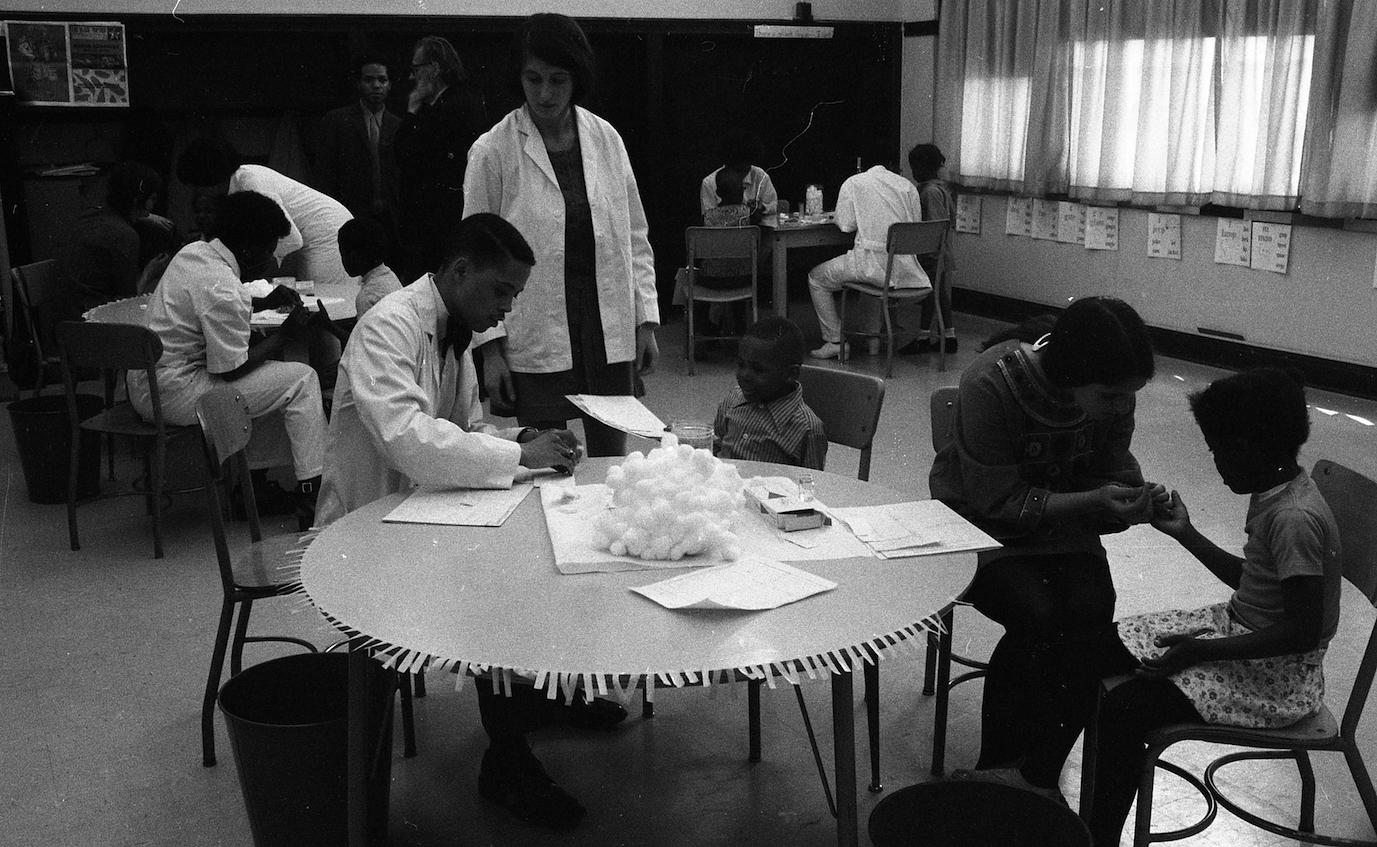

Perkins was a reformer, not a revolutionary, but his shadow is long enough in Chicago that more radical strains of activism would come to understand the value of his schools, just as he had. In 1971, the Chicago chapter of the Black Panther Party held sickle cell anemia testing at his William Penn Elementary School on the city’s West Side. Its mascot is the panther to this day. For both the Marxist Panthers and the reformer Perkins, public health was a right to be exercised at the school house.

Perkins didn’t get everything right. He was too optimistic about public schools’ ability to break down the barriers to true multicultural democracy. But his example is a piercing shriek of defiance for a populace lulled to nihilist complacency by the laissez-faire metropolis’s progeny, neoliberal austerity. “I wish we could return to the optimism that someone like Perkins and the whole progressive crew had,” Gray told me, “because they believed that as citizens, they had the power to advance change and try to improve things.”

There are other ways we’ve lost Perkins’s thread on what makes enduring architecture. So much debate and animosity today around the role of the built environment centers on how buildings look. This has always been the case, but lately, culture-war grievances have reached into the architecture discourse, plucked out a privileged set of styles and aesthetics (traditional, Classical, anti-Modern), and defined them as uniquely befitting American democracy and Western values—stuff Perkins took very seriously. To Gray, and to anyone who has thought about architectural history for more than five minutes, this is ridiculous. “You cannot link one particular style of architecture to something like democracy,” she says.

Soviet despot Stalin adored a Classical cake-topper, and weird art lefties at the Bauhaus came up with Modernism, and yet a few decades later it was the face of global capital. Style and aesthetics mean different things over time and space, and context matters. Style is a product, an outcome. How buildings work and function over time, which consumed Perkins for almost all of his days, is a process: iterative, messy, and unfinished, Gray says, just like democracy itself.