Julia Gamolina (second from left) with her cousin, grandmother, and aunt at her favorite place at the dacha: the swing.

Gamolina with her grandmother and cousin, Vadim, in front of the house’s forest wallpaper.

Vladimir Nicholaevich Diukov, Gamolina’s grandfather, built the dacha himself.

In the TV room, with Gamolina’s brother and cousin.

Julia Gamolina is the founder and editor of Madame Architect and an associate principal at Ennead Architects.

“I’m from Novosibirsk, the third-largest city in Russia, where I lived until I was 8 years old. I spent my summers going to our country cottage, or dacha—a housing concept that has been ingrained in Russian culture for centuries, but became popular during the Soviet era—in the forest, about a half-hour ride away.

The government used to own a ton of land—now a lot of it is private—and then invite organized communities of fifty to one hundred families to buy parcels of that land. There’s nothing on it. You buy a piece of land, and you do with it what you will.

My grandfather, who has a construction and civil engineering background, bought a piece of land and built a shed on it, for storage. If he ever wanted to come to the country, there was a place where he could put his things over time. Eventually, he built a three-room house, entirely out of wood. Then he built a veranda, then an upstairs, then he expanded the upstairs.

By the time I started going there, the house was surrounded by a garden, where we grew all kinds of vegetables. It also had greenhouses, an outhouse, and a sauna, something very popular in Russian culture. There was a swing by a seaberry tree—all together forming this idyllic little world for me and my family.

I felt very safe, cozy, and free at the house. It was very self-sufficient. We had everything we needed, and we provided it for ourselves: collecting rainwater, growing our own food, pickling things in the cellar for the winter. We always had fresh air. It was very different from our dreary apartment complex in Novosibirsk.

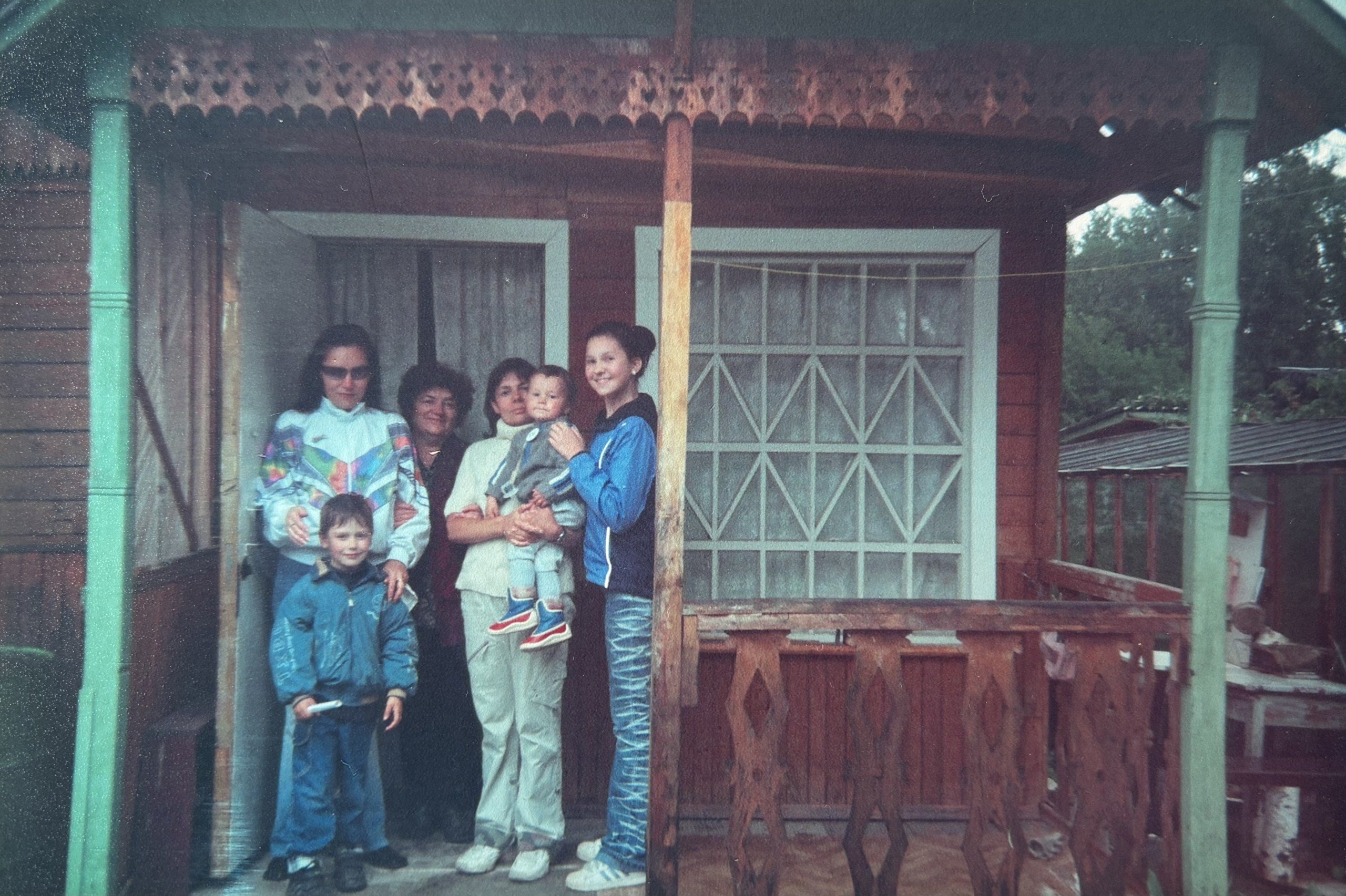

Gamolina’s family on the dacha’s front porch.

Near the garden, Gamolina holds a toy next to a friend.

Bike-riding among the surrounding dachas.

Gamolina and her cousin having a shashlik, or grilled-meat, lunch inside the home’s veranda.

Living there taught me that a quality home is built step by step, and very genuinely based on what you need and collect through your life, and not about buying a cookie-cutter place. I’ve seen so many books on home and interior design where the homes look like they’re out of a catalog. There’s no aspect of personalization: Everything looks the same and matches a little too well.

The dacha is extremely family-oriented. That’s the dacha experience: You came there for the summer, and you were there with your family, and it was multiple generations, all together all the time. I don’t know if I see that very often in the United States. Here, it happens on Thanksgiving, but in general, I feel like the U.S. is very individualistic.

At the time I was in Russia, at least when my parents were growing up there, it was very much about community. I’m a huge fan of intergenerational housing, which I think comes from growing up the way that I did in the summer cottage.

It allowed us to build a better understanding of humanity—what a child is going through, what a grandfather is going through. You’re in there together, talking about it all. There’s something about multigenerational sharing, and housing, that enables a person to be a more empathetic human.”

This conversation has been edited and condensed. (Photos courtesy Julia Gamolina.)