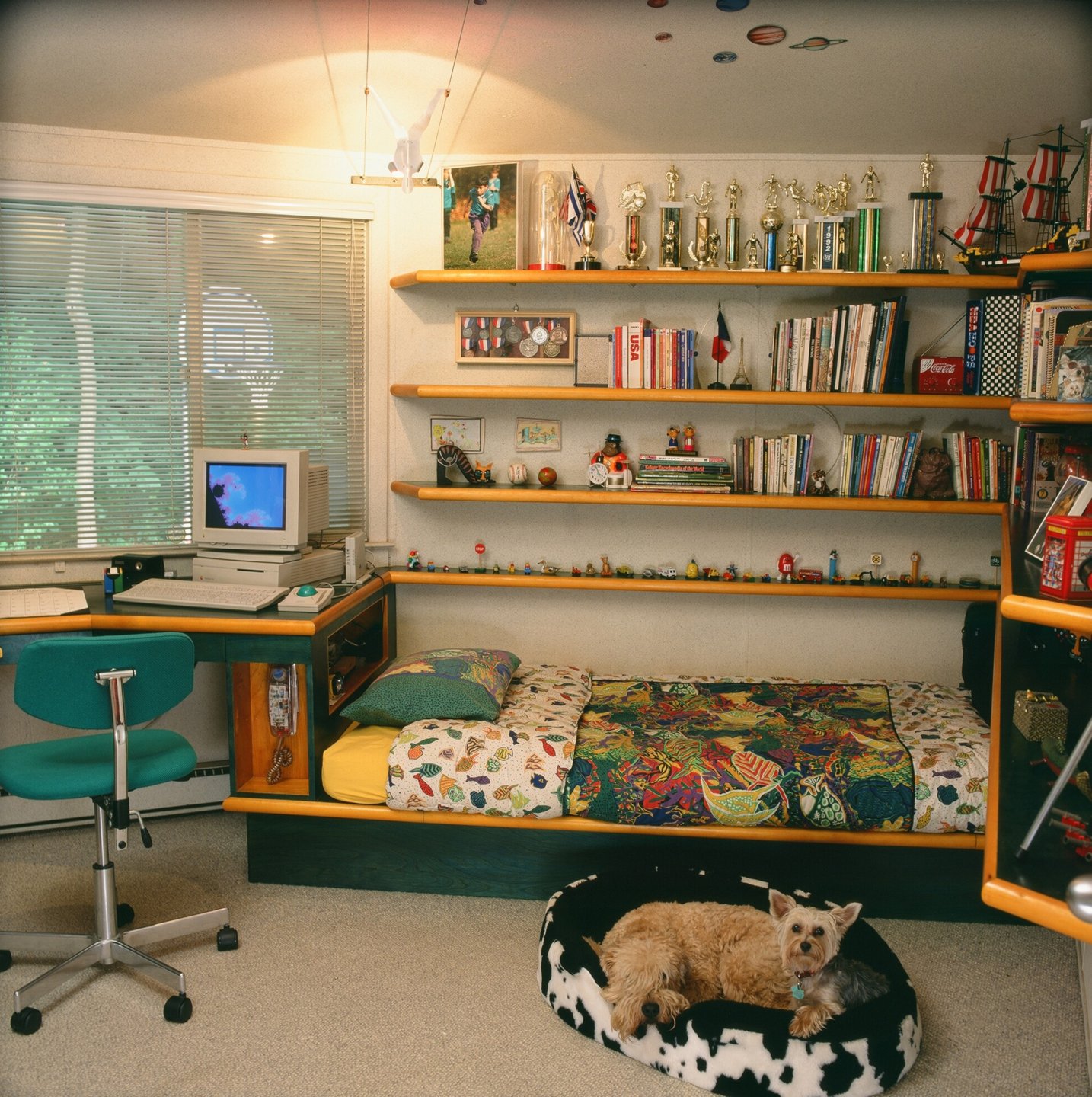

Tal Schori’s childhood bedroom.

Schori’s home, located in the Usonia community in Pleasantville, New York.

The family’s kitchen, with cabinets embellished with images by his mother.

Tal Schori is a founding partner of GRT Architects.

“I grew up in Usonia, a Frank Lloyd Wright community in Pleasantville, New York. It was established in the 1940s by a group of progressive-minded, middle-class Manhattan professionals wanting to build a community based on the cooperative housing model, which they really believed in. They met on weekends and evenings, searching for land to build it on.

At one point, one of the people leading the group switched careers, from being an engineer to an architect, after seeing an exhibition about Wright. This guy ended up going to Taliesin, met Wright, and convinced him to help create this new community outside the city. Wright was in his seventies at that point, and very accomplished, but he was inspired by this young man, these individuals, and their passion for the project.

Wright ultimately designed the master plan for the community, which was forty-eight houses at the time. Only three of them were built [by Wright], and the rest by his disciples, architects who were part of this community.

The master plan was incredible, and had a significant impact on me. The way he did it was: Everybody’s lot was circular and the same size, about an acre. Imagine a table full of pennies, squished all together, and the spaces in between the pennies. One of the bylaws of the community was that you weren’t allowed to build in those spaces. This was in direct contrast to a lot of early suburban post–World War II development, which was mostly rectangular lots, giving rise to the picket fences that became synonymous with American suburbia. In Usonia, you only touched your neighbor’s property at one point, and all those open spaces had to remain undeveloped. They remained forests.

You also weren’t allowed to put fences around your property. So where your property began and the next person’s ends was ambiguous to the naked eye. There was this sense not only in philosophy, but also in practice and physically, that everybody’s land was shared. That had a big influence on the way it felt to live in this community.

Growing up, I was surrounded by forest. You’d leave the main streets of my town and enter the roads of Usonia, and there was a different acoustic nature to it. There was a different light in there, too, because it had a different ethos and physical makeup that was astounding and noticeable. There was a community pool and community tennis courts. Everyone got to know each other by going there on the weekends. There were monthly community meetings for the people who owned the houses, where they discussed their bylaws or people who wanted to make renovations. There was a real sense that decisions were made together.

When I lived there, there were still a large number of original owners from the time of the community’s founding: real diehard socialists and people who believed in this notion of communal ownership of land, of even the homes themselves. Early on, you didn’t purchase a home. You purchased into the cooperative, and the cooperative money built your home, which is common in New York City with co-op apartments, but rare with single-family homes.

My house was actually the forty-ninth house. It wasn’t built during that initial period, and it was the only house that was added to the community. This is because the owners of my house had lived previously in Usonia in one of the original homes. When that couple retired, they moved to Cape Cod. Then they missed Usonia so much that they wanted to move back, but there were no houses available. So they asked if they could purchase an adjacent plot of land and be absorbed into the community again, which happened.

They built this house around 1969. Unlike all the other houses, it was a prefab house. I don’t know the history of the model, but it was in the spirit of the Usonian homes, modern and progressive. The house went on the market in 1987, when I was 6 or 7 years old, and my parents, who’d moved here from Israel right before I was born with a suitcase to their names, bought it.

Even the bathroom expressed the spirit of the Usonian homes, modern and progressive.

A spiral staircase and a terrazzo-enveloped fireplace in the family room.

Forests surrounded the home, underscored by its picture windows.

Our house was ‘the brassiere house.’ That’s how it was jokingly referred to sometimes, anyway, because, from above, it was two twelve-sided polygons attached by a narrow rectangle, and it was perched on a little slope. It was two stories high, but in the front it was one story high, and you entered right in the middle, between the polygons.

Once inside, on the right was a big open, twelve-sided space with a little vertical divider, separating the kitchen, dining, and living rooms. To the left, the other circle was divided up into a bunch of pie-shaped slices of different proportions. My younger brother and I shared a room, my parents had their bedroom, and there was a TV/guest room. A spiral stair led you down into the basement.

It was in a bit of disrepair, but my folks didn’t have much money then to do anything about it. My dad was trained as an engineer (he later went to night school to earn his M.B.A. and then pivoted to Wall Street), and my mom used to have a furniture store in New Jersey full of old Memphis stuff, really ahead of its time. In our house, she was constantly making little fixes. Whatever she could do on her own, she would.

Early on, I remember my mom with a slide projector, projecting vintage Victorian ink drawings of kitchen utensils onto the cabinets. She’d trace them with a sepia-tone marker onto the cabinet faces. From somewhere she procured a white terrazzo with colorful glass chips that surrounded the fireplace in a way that felt very Memphis at the time. She also put picture frames around some of the windows. That was a bit on the nose, but as a 7-year-old, I thought it was incredible.

One thing that has always stuck with me: My mom had a great sense of how to make something feel coherent without making it feel dull. One of the things she latched onto was the house’s odd geometry. She’d do things like make the handle of the cabinet that held the stereo the same shape as one of those twelve-sided shape slices. These details were small but playful, and had a logic to them.

My brother and I put a stamp on our bedroom and my parents on theirs and such. But there was an overall vision for the entire building from an architectural standpoint that was initiated before anyone moved in. That’s part of the Usonian homes. There was a real value placed on architecture as a way to create light-filled spaces, for spaces to come together and to be apart. There was a sense that architecture could enable those different experiences. I appreciated that, and it stayed with me as I developed my own aesthetic.

Everyone I knew in school lived in one of those ‘other’ houses. There was this sense that our house and the ones directly around it were well proportioned. A small modest house could be more expansive and more pleasurable to be in than a large house, where every bedroom and appliance is giant and there’s a two-car garage. (Usonia was all carports.)

There was also this sense at home that things were mutatable: You could adjust them and always improve on them and continue to think about them differently. You understood that things could evolve, but it never felt like anything was unfinished.”

This conversation has been edited and condensed. (Photos courtesy Tal Schori)