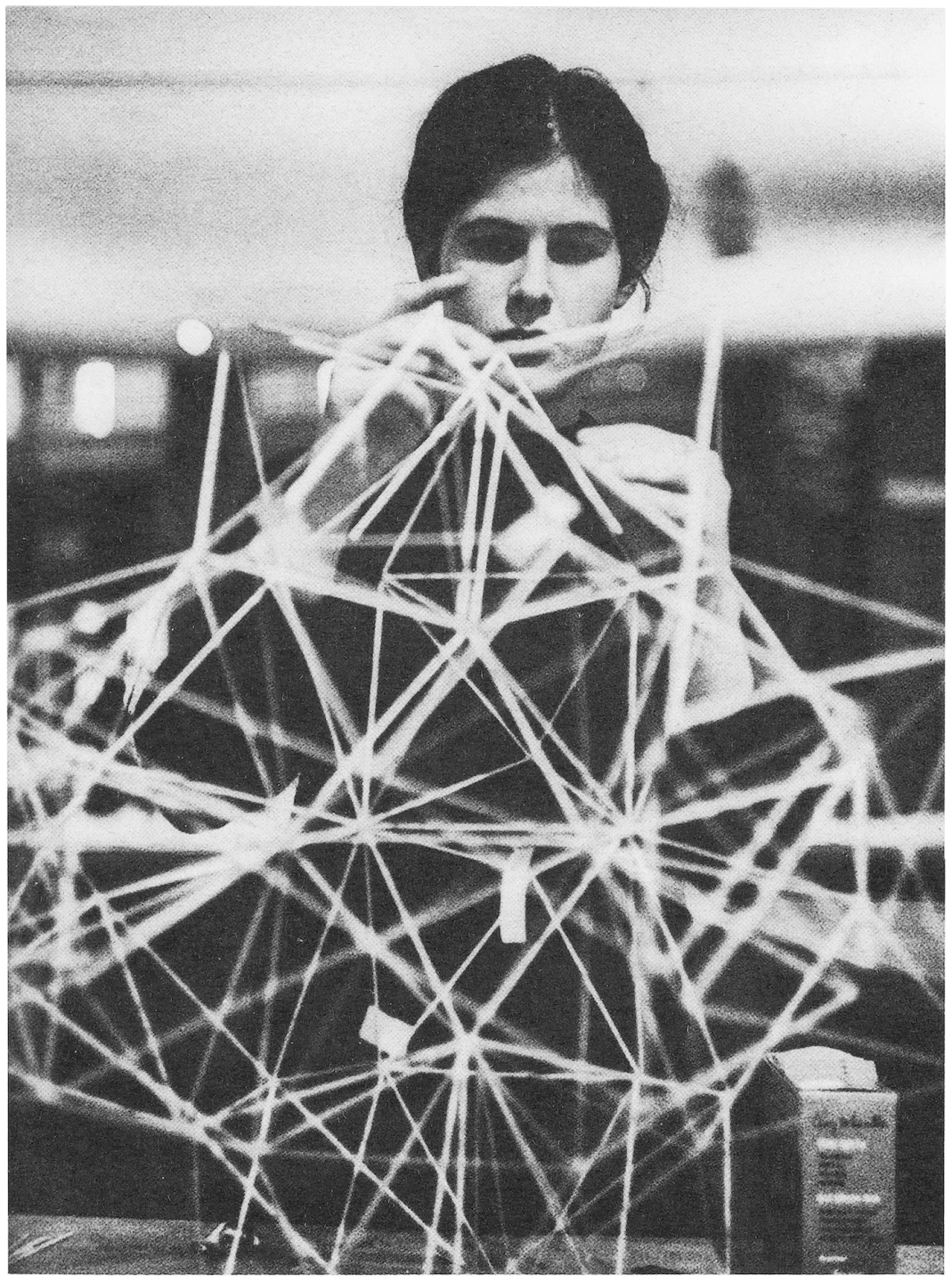

A student at Harvard University’s Carpenter Center builds a three-dimensional structure based on equilateral triangles, using a fragile material to test the structure’s stability. (Courtesy Inventory Press)

Like you and me, Bruno Munari (1907–1998) contained multiple selves. But mapping the Italian designer, artist, and inventor’s various outputs across the arts onto a single person seems beyond the bounds of possibility. He knew it, too. As he was fond of saying, “Everyone knows a different Munari.”

He developed educational games and wrote and illustrated children’s books. Associated with the Futurist movement, he served as the art director for various magazines, designed hundreds of book covers, and wrote prolifically about what it means to create and to see. He curated exhibitions and hosted a television program. He produced formal experiments he called “useless machines” and “unreadable books.”

This month, through his own book Design and Visual Communication (Inventory Press)—first published in 1968 and now translated into English for the first time—we get a clear glimpse inside yet another Munari identity, one that would shape the second half of his career: teaching. Translated by cultural historian and Munari scholar Jeffrey Schnapp, the book is both a practical guide and a theoretical text on visual language, the result of Munari’s time as a visiting professor at Harvard University’s then recently opened Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts.

It follows a similar format as Design as Art, a book Munari published two years earlier and that is still perhaps his best-known work among designers. For that title, Munari collected a series of essays on design that blended reflections on his own polymathic practice with arguments for design’s role in connecting art with the public and the everyday. Design and Visual Communication also mixes the personal and the public, but in a more approachable way.

This is Munari’s first “conventional book,” as Schnapp calls it in an included contextual essay. “Its scope and ambitions are more sweeping,” he writes, “and its core argument more systematic.” That ambition is to test new methods of teaching visual communication—by using the latest tools and technology, and by focusing specifically on educational contexts—and to position adaptability as a key aspect of practicing design.

Munari defines “visual communication” as “almost everything that our eyes experience […] a cloud, a flower, a technical drawing, a shoe, a poster, a dragonfly, a telegram qua object (leaving aside its content), a flag.” For him, visual communication are images that take on meaning or convey messages. These messages can be random, such as a cloud or a dragonfly, or intentional, such as technical drawings, press photographs, or signage on the side of a road.

The designer of these messages makes a series of aesthetic choices that must be connected to the message they’re communicating. The viewer, then, receives these messages—both random and intentional—and projects their own meaning onto them, drawing from their own background, aesthetic preferences, and cultural context.

Considering how viewers process what they see, Munari claims, is the key to successful visual communication. So designers ought to ask: How can we look beyond traditional notions of beauty, instead considering “what is right or wrong,” as he puts it, for a given context? How can we connect objective communication to aesthetic visual form? How can we organize a surplus of information into understandable systems? (Nearly six decades later, designers are still working through these questions.)

Separated into two parts, Munari outlines dozens of lessons he taught during his semester at Harvard, often drawing on a range of influences, including the experimental work happening at Germany’s the famed Ulm School of Design, Umberto Eco’s work in structuralism, and Maria Montessori’s work around childhood education.

The first section, the text-heavy “Letters from Harvard,” collects 20 chapters—many originally written as a series of dispatches he was commissioned to write for the Italian newspaper Il Giorno—that describe both his teaching philosophy (“To get to know the images that surround us is to expand our potential points of contact with the world”) and his impressions of Harvard (“Above me, between the ceiling and the slate-covered roof, resides a squirrel whom I’ve never actually met but whose gnawing can be overheard, especially at night”). Munari’s writing is both reflexive and digressive, the casual tone obscuring the density and range of ideas.

The second section, “Visual Communication,” moves from theory to practice in highly illustrated chapters that range from “Textures” to “Decomposing messages,” to “Color use for designers,” each presented with a range of examples from history and the Harvard course. The class, called Advanced Explorations in Visual Communication, centered around what Munari defined as “visual research,” which he compares to a type of avant-garde–ism: an exploration of new ideas “propelled forward by technical considerations.” Students explore various formal attributes, including structures, textures, and geometry, as well as how tools influence the way images are perceived. “Designers are entirely free to select the right materials and tools in their pursuit of expressivity,” he writes. “They can develop a wide array of solutions for adoption in the proper context.”

Munari spends little time on those solutions, however, focusing instead on the process and the ideas that underline a given work. For him, design is not a strict set of rules, a specific range of formats, or even discreet professionalized disciplines. Instead, it’s an approach, a way of seeing and making sense of the world—the output of which could take any form.

To demonstrate this, he describes two ways to structure an educational design program: static or dynamic. “The first forces individuals to adapt to fixed schemes that are almost always outdated or soon-to-become outdated due to everyday practicalities,” he writes. “The second implies a constantly shifting approach, suited to the needs of individuals and the present challenges they encounter.”

In other words, one can teach through a set of rules to be followed—or one can teach flexibility and exploration, acknowledging that culture, technology, economics are forever shifting our relationship to design, therefore challenging and shifting what design itself can be. And it’s here that we can see why Munari’s work continually finds new readers. Despite rooting his work in his own context, the ideas he puts forth are strangely timeless: both technology- and media-agnostic.

The visual communication of the 21st century is even more chaotic than the one Munari was responding to. Design, of all types, is increasingly complex: Our houses are now smart homes, the apps on our phones plug into a complex urban infrastructure so we can order food, and social media dispenses endless visual communication—both random and intentional—that we need to make sense of daily.

In Design and Visual Communication, Munari writes of a design that is not a finished artifact or static in time, but that is a living process that puts us in dialogue with the world and with one another. This sounds like the kind of design we need more of now than ever. It would be playful but rigorous, intentional but fluid, experimental but intelligent, and, as always, unabashedly multidisciplinary.

Design and Visual Communication will be the focus of the October 21 gathering of the New York Architecture + Design Book Club, a quarterly book subscription and event series organized by Untapped and the Brooklyn bookshop Head Hi. The program will take place at Manhattan’s Center for Architecture and feature Jeffrey Schnapp, whose annotations contextualize the new translation, in conversation with Nontsikelelo Mutiti, director of graduate studies in graphic design at Yale University. Find out more and RSVP on the book club’s website.