English-language media’s coverage of Xiyadie, the Shaanxi-born, Beijing-based paper-cut artist, often portrays him as a rebellious queer artist working within a conservative Communist society. But these convenient labels struggle to land on the lush and tormented tableaux of Xiyadie’s life and art. His stunningly complex compositions chart both personal narratives—including his experiences as migrant worker, folk artist, queer artist, father, and guilt-laden husband—and an idiosyncratic cosmology of queer navigation and belonging.

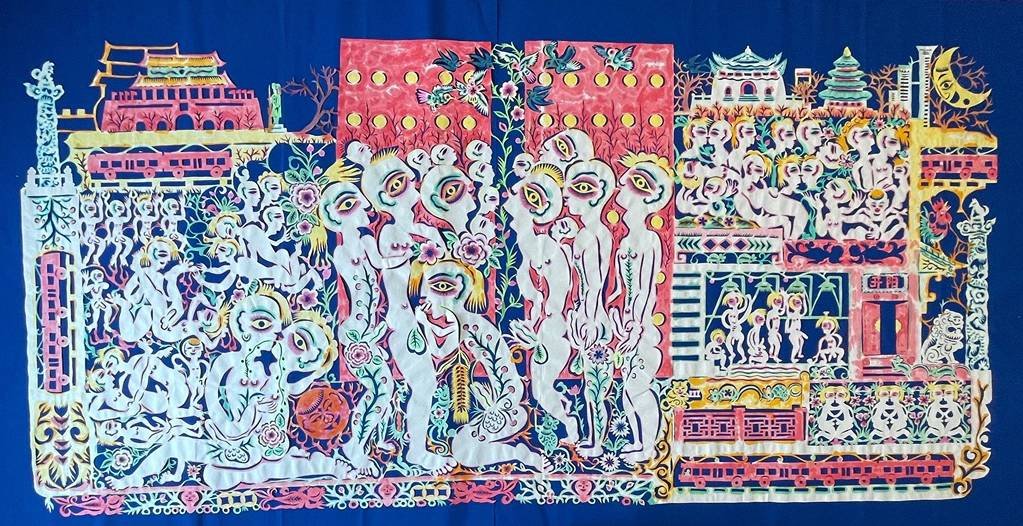

Xiyadie’s most ambitious project to date, “Kaiyang” (2021), measuring nearly 10 feet wide and recently exhibited at Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt, chronicles his 2005 introduction to Beijing’s underground queer scene: One cold night, the artist had been cruising around near Dongdan Park—a popular spot near Tiananmen Square—and missed the last train home; a boyfriend took him to the famed Kaiyang Bathhouse, where one could spend the night on the cheap. There, Xiyadie found both temporary shelter and lasting community—one he couldn’t dream of in his hometown. “Kaiyang” describes the night’s reverie in detail: bodies entangled and metamorphosed into flowering trees during group orgies, then intricately laced with traditional decorative motifs; a lurking moon and sun alongside Beijing landmarks old and new. The sense of joyous harmony compelled the artist so much that he recalls the night in the bathhouse as “Beijing’s warmest spring.” During our interview, the artist’s poetic and near-cinematic description of this memory—as well as others that would inform his compositions—often evoked Stanley Kwan’s 2001 film Lan Yu, in which relational and political volatilities are grounded in, rather than dictated by, struggles of intimacy.

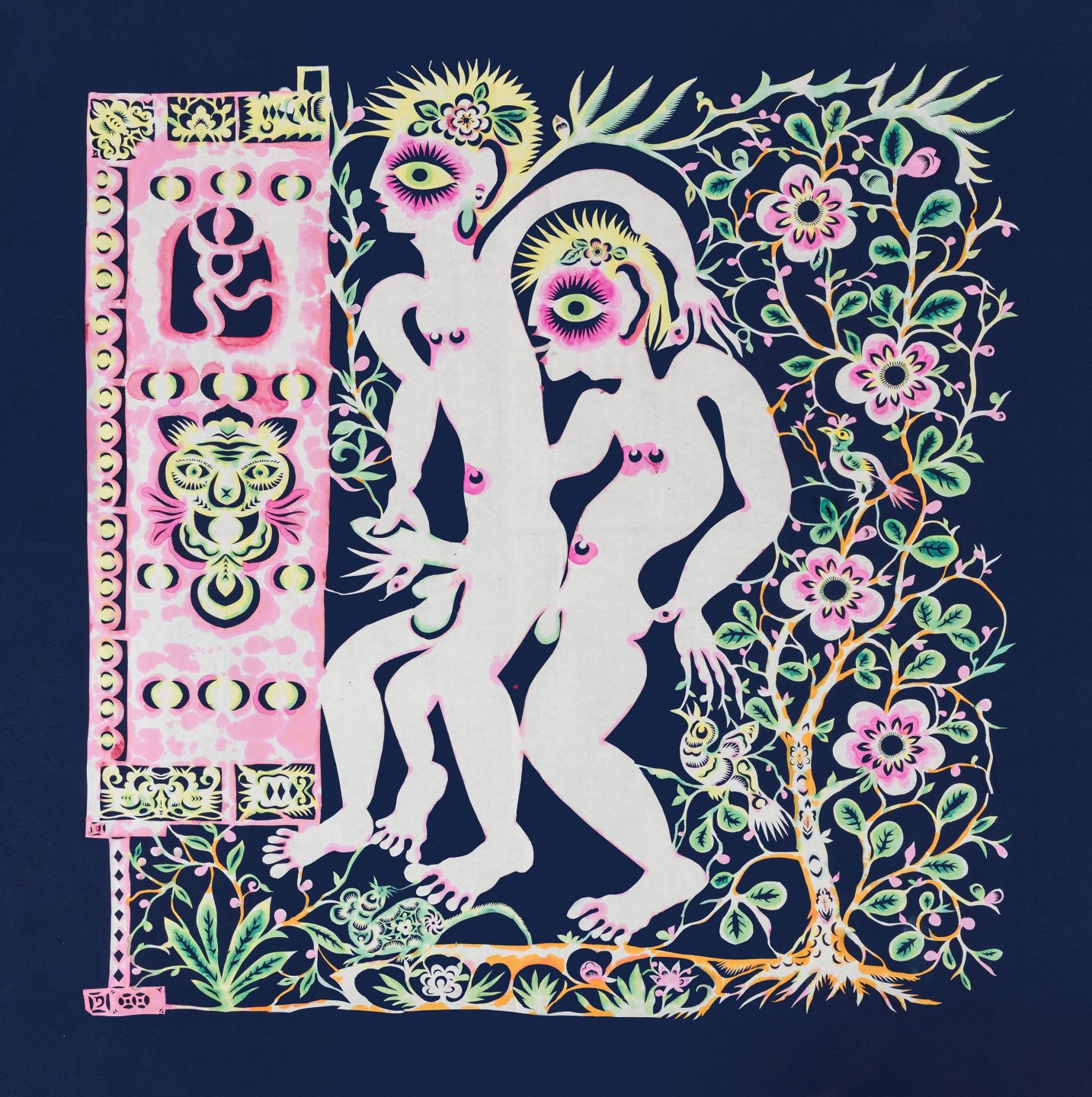

The artist’s name, a pseudonym, translates as “Siberian butterfly,” an extraordinary creature capable of surviving and flourishing in harsh conditions; it also centralizes the idea of beauty, which, according to the artist, has been the most potent force in his life. The continuous, morphing connection from one motif to another is crucial to the medium and craft of paper-cutting, with its robust folk-art history stretching back two millennia in China. It’s also not hard to read erotic, queer connotations into this medium-specific condition, which Xiyadie exploits exuberantly to visualize one-ness with other desired bodies, as well as with nature. The way his figures transform into trees, flowers, and ears of wheat has a fantastical naturalism redolent of Bernini’s “Apollo and Daphne” (1622–1625)—though for Xiyadie, this metamorphosis also underscores the plain yet fundamental idea that queer desire is natural, innate, and moves at a pace that, as he puts it, is “constant, like the universe.”

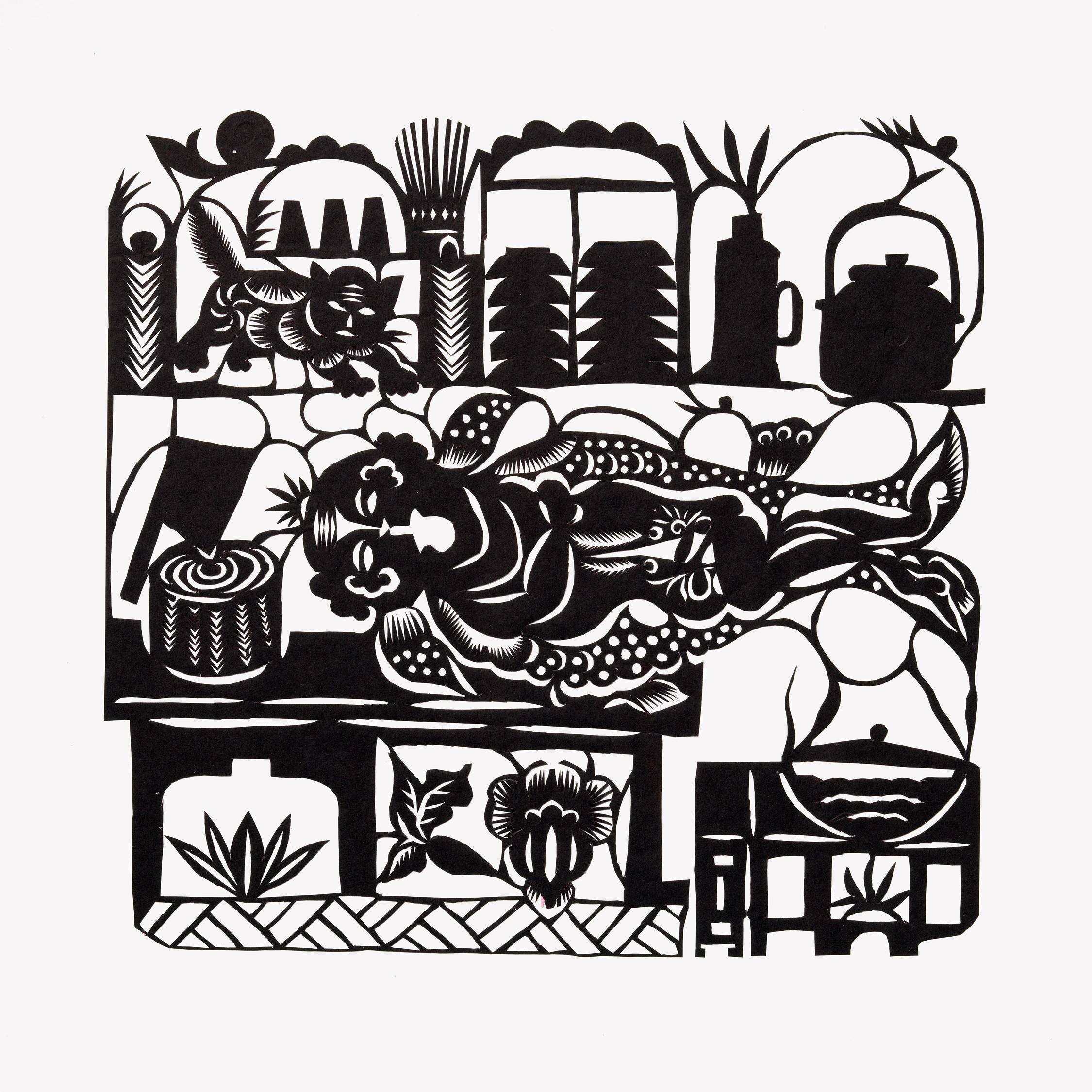

He has not arrived at this understanding swiftly, or easily. Feeling trapped and guilty toward his wife, he has taken sleeping pills in attempts to cure himself of homoerotic desires. When the recurring motifs of doors and walls appear in his compositions, they often accommodate deeply conflicted feelings about safety, suppression, domestic life, and shame. Against these confinements, however, unruly desire abounds and flows, which he compares to “a branch of apricot flowers coming out of the wall”—a well-known Chinese idiom for illicit affairs that Xiyadie particularly likes to evoke.

As much as they are suffused with folkloric references and traditional symbolisms native to paper-cutting, Xiyadie’s compositions are equally rich in time-specific cues, such as a logo from the 2008 Beijing Olympics, or a soldier standing guard on Tiananmen in Kaiyang. While the medium typically serves festive or talismanic purposes with a rich, developed iconography and an elaborate process of cutting and dyeing (of which the artist has a masterful command), Xiyadie has ultimately recalibrated the art form’s vocabulary for new syntaxes. For the artist, it’s important to have anchors of the present, so that the various motifs, connected like a neural network, can produce a cosmic constellation in which lives like his can thrive and, at last, make sense.

In the works below, Xiyadie discusses some of the pieces that feature in “Xiyadie: Queer Cut Utopias” (through May 14), his first solo exhibition in New York that opened earlier this month at The Drawing Center. The artist speaks of his creative process as planned yet spontaneous, as new patterns and ideas often unexpectedly emerge. Of the method, he says, “It’s even richer than language.”