In the early 1960s, the Better Homes & Gardens Decorating Book was a common guide for “homemakers,” the primarily female cohort sustaining the single-family homes that dotted the suburban American landscape. “It’s your home,” the interior design catalog assured its audience. “What kind do you want?”

In retrospect, its vast range of colors, textures, patterns, juxtapositions, and furnishings of past and present styles offered the illusion of choice to readers that, in reality, had little way out of the roles assigned to them at birth. Flipping through its cheerful, glossy pages, the catalog’s target audience may have reasonably wondered: How deep can the search for decoration that “reflects the personality” of my family really be in a society in which everyone, more or less, has a predetermined part to play?

The remaining years of that decade were rocked by a series of cultural revolutions—sexual, racial, environmental, and political—that, each in their own way, invited the next generation to consider the past as needlessly repressive, and the present as a buffet of previously unimaginable lifestyle options. While many countercultural leaders were skeptical of aesthetic treatments as mere façades of social progress, others maintained that liberation would represent itself through home decoration.

Little information can be found online about Norma Skurka, a design critic and close observer of midcentury cultural movements, yet we can find ample inspiration in her ability to locate personal freedom within ornament through her opinion pieces in newspapers and a handful of design-theory books. “The seventies are emerging as a decade of involvement,” she prophesied in one of her first pieces for The New York Times, in 1970. “Concern for a better environment, social and physical, is having its impact on the home. Gone—or going—is the static house that echoes hollowly the latest trend. In its place is the home that mirrors a lifestyle.”

Skurka’s first book, Underground Interiors, published in 1972, was decidedly geared not toward “homemakers,” but rather anyone willing to approach the late 20th century as an era of radical self-expression. Her relative disapproval of both traditional and modern styles—given their shared allegiance to signs of wealth, etiquette, and efficiency—captured the spirit at the heart of postmodern design: “Man is an emotional animal,” she wrote, “drawn as much to beauty as he is to lack of logic.”

Altogether, her book’s interiors strove to unmake the nuclear family by revealing the many ways that décor could shelter and elevate the various living patterns that were being fought for in parallel protests and cultural shifts. Considering that the five stylistic categories Skurka developed are each a direct affront to the status quo that has shifted far too little since the book’s publication, Underground Interiors is just as instructive today as it was half a century ago.

Her first classification (each is given its own chapter), Surrealist Interiors, depicts interior design as having the capacity to expose the “absurd conditions of contemporary life” through their amplification. It begins with a full-bleed image of artists Antony and Dorothée Miralda’s ceiling-height wedding cake sculpture that occupies nearly all the floor space of a room saturated with visual and comestible amusements that would make Willy Wonka blush. Less appetizing than off-putting, the so-called “cake room” is, for Skurka, “a symbol of the relentless consumption of today’s civilization—a society reared to consume everything with insatiable appetite—the planet’s raw materials as well as the endless stream of commercial products—a society chomping through the natural and commercial landscape like a swarm of locusts.”

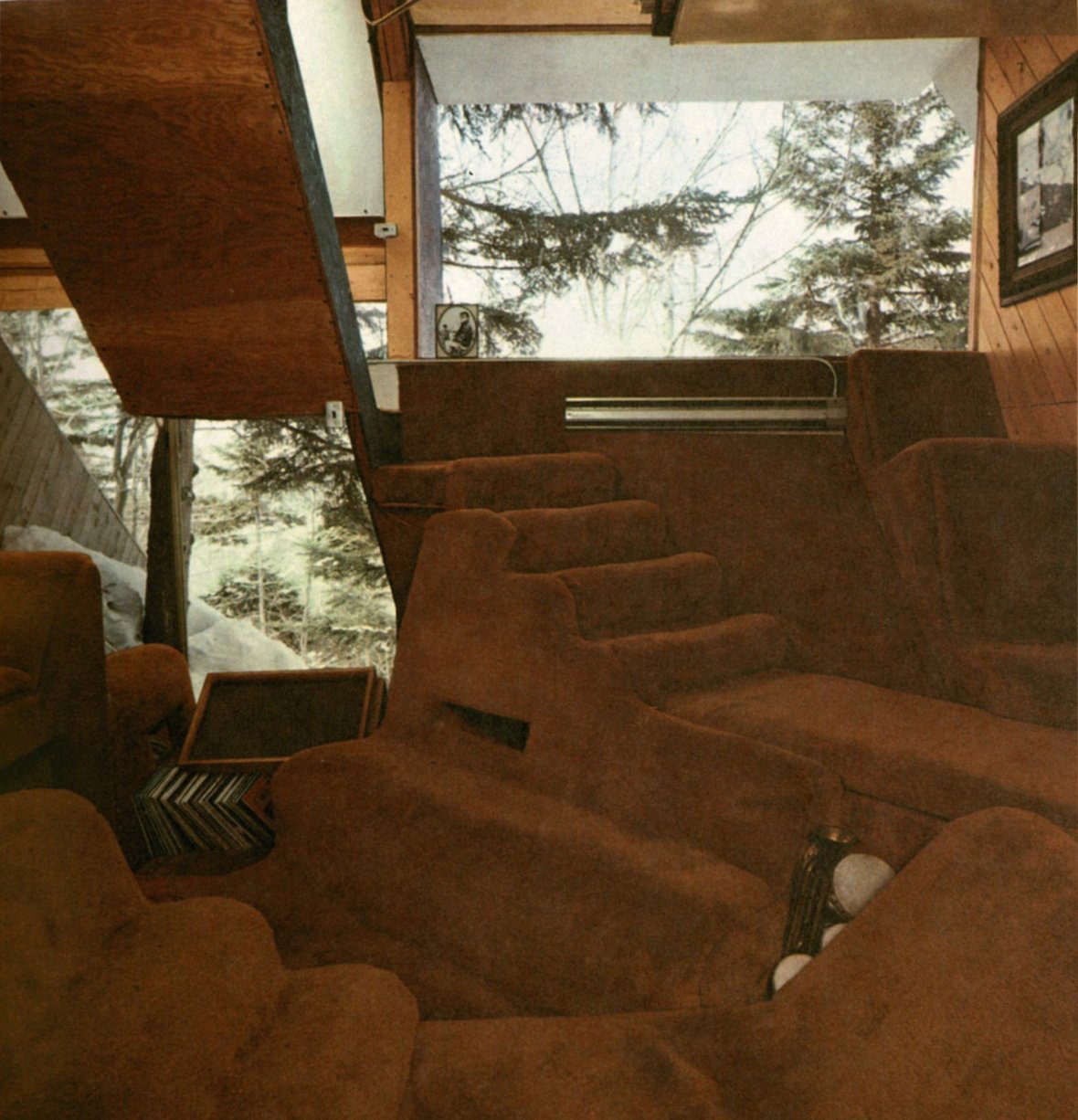

She takes this critique to its opposite extreme in the next chapter, Environments, by depicting minimalism as a moral obligation far beyond decorative connotation alone. “Environmental design is primarily a streamlining of our living habits, and thus, of our habitations,” Skurka writes. “It is a redirection of our concepts about living.” A nascent conception of environmentalism is expressed through spartan living rooms pockmarked with anti-object furniture sprouting from thick shag carpets (such as a apartment for Mr. and Mrs. D. Elmann that its architect, Paul Rudolph, described as a “moonscape”) that take the “return to nature” movement more figuratively than literally.

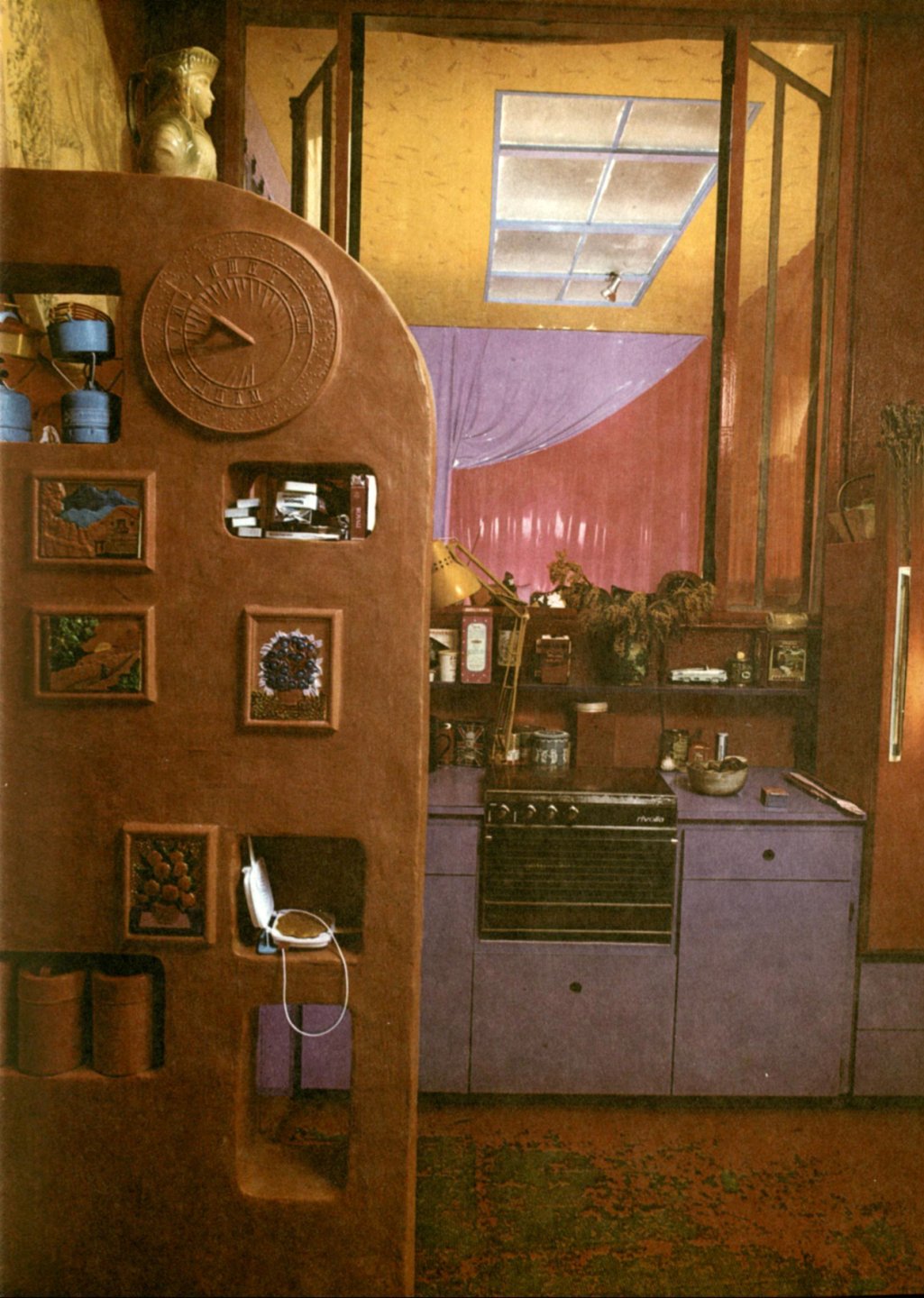

The third and fourth classifications disavow that fickle target known as “good taste”—a term the author believed had been co-opted by powerful markets to homogenize the masses—through differing means. The former, Radical Chic, counters “establishment chic” with bathtubs in kitchens, disorientingly reflective surfaces, and the interspersion of tchotchkes and objets to locate beauty in the eye of the user. “Radical Chic is above the shallowness of fashionable decoration,” Skurka writes. “It exists in the exploration, the discovery by oneself of the accessories or embellishments that please in themselves.”

The latter, Pop Culture, reappropriates the visual tools of advertisements and mass media as tools for self-empowerment. Supergraphics, the large-scale graphics that popularly adorned interior surfaces throughout the late 1960s and early ’70s, represent, for the author, an inexpensive yet impactful method of transforming space, “a reaction to the lack of character in domestic architecture.” The home of the architect Charles Moore illustrates the humorous appeal of adapting billboard aesthetics to a space for hosting guests, where a cutaway wall reveals a full-sized trompe l’oeil sticker of a dapper man looking out to the adjacent terrace.

Finally, Skurka envisions Space Age Habitations as a set of aesthetic sensibilities thrust into the 21st century by the moon landing and other midcentury marvels in technological innovation that, perhaps, could unburden people from the tedium that had led to gender divisions and other repressive social constructions in the first place. “We will become accustomed to living in and being surrounded by synthetic materials, be they fiberglass, foam, plastic, or materials not yet invented. But no longer will synthetics be required to copy wood, re-create stone, or simulate marble as they have been forced to in the past,” she explains. The hyper-smooth interiors of glossy plastic, metallic reflections, and tubular steel appear as superficially ultramodern at a glance—and as playfully impractical upon closer inspection.

Politically progressive, design-conscious, and cash-strapped, the millennial generation has much in common with Skurka’s intended audience of the early 1970s. The thirtysomethings of today might use Underground Interiors as a guide for airing their grievances about the apparent futility of recycling plastic through a Surrealist Interior of their own. Those experimenting with polyamory or an indefinite adult roommate-ship might apply touches of Radical Chic to legitimate their newfound arrangement. Pop Culture embellishments could suit the needs of a media blogger on a budget. Skurka set up the possibilities to be endless.

If interior decoration can communicate values as persuasively and immersively as a social media profile, then our task must be to locate in the present what Skurka had discovered “underground” in the past, and bring it to the surface.