“Old Tree,” a 25-foot-tall sculpture of a tree and hyperrealistic but for its screaming-pink hue, materialized in early May on the Spur, a segment of New York City’s High Line that sits above 10th Avenue. Created by Swiss artist Pamela Rosenkranz, it’s billed as a reflection of, as High Line Art curator Cecilia Alemani put it, the “High Line’s complexities as both a natural landscape and a built structure.” Maybe that doesn’t sound so profound, but the artwork, which I first glimpsed in an almost hallucinatory flash of color as I drove uptown, resonated so strongly with me that it felt as if it had somehow burst from my own consciousness.

I’ve been thinking a lot about trees, specifically about where and how we plant them. I have this sense that, as we incorporate trees into the built environment—something we’re doing more routinely as our need to remove carbon from the atmosphere becomes undeniable—we’re forgetting the simple fact that they’re alive, and that they have needs that may not neatly dovetail with decisions made by teams of architects and designers.

After all, trees have an agenda, too. At least that’s the message of recent books such as forester Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees (2015) and scientist Suzanne Simard’s Finding the Mother Tree (2021). These books advance the alluring idea that trees are sentient beings, capable of communicating with one another via underground networks of roots and fungi. (I don’t think it could be an accident that Rosenkranz’s tree can also be read as a jumbo cluster of neurons.) And trees, unlike humans, are long-term thinkers, with little use for concepts like efficiency and expediency.

This makes trees’ increasingly ubiquitous coupling with buildings—where they’re often planted in ways that appear restrictive and overtly unnatural—particularly puzzling. If you’re the kind of person who looks at architectural renderings, you’ve surely seen a number of them in the past couple of years that show acutely modern structures bristling with trees. It’s as if a committee somewhere decided that skinny birches and pines standing at regular intervals on every possible surface were a new form of ornament, a 2020s spin on the concept of postmodernism.

My thoughts on this fashionable hybrid of organic and inorganic were initially triggered by Little Island. In the spring of 2021, soon after it opened, I wandered the $260 million, 2.4-acre parklet on the Hudson River, privately funded by billionaire media mogul Barry Diller and willed into existence by Thomas Heatherwick, a British designer known for creating high-priced architectural novelties.

Heatherwick worked with the New York landscape architecture firm MNLA to install—plant seems like the wrong word—trees. Many of them were what he referred to as “hero trees,” 20,000-pound specimens that had to be airlifted onto the island via crane, where their roots were anchored with steel cables embedded in the island’s concrete slab. It was this heavily leveraged merger of the natural and the manmade that made me start noticing how architects, in general, were deploying trees.

Architects, of course, have been preoccupied with trees since day one. For instance, in his 1988 book The Lost Meaning of Classical Architecture: Speculations on Ornament from Vitruvius to Venturi, the late Yale art history professor George L. Hersey notes that the defining feature of classical style—the column—was, metaphorically speaking, a tree. Groves of trees were the original places of worship for the ancient Greeks. Then, Hersey writes, as they began to design and build temples, those sacred woods were stylized and smoothed into lines of columns. “If we put this all together,” Hersey wrote, “we can see the temple as a grove of sacred trees.”

Hundreds of years later, André Le Nôtre, the 17th-century landscape architect, lined the trees of Versailles into allées so straight and rigid that they might as well have been colonnades of stone. In the 20th century, Cesare Leonardi, the Italian architect who, working with his partner Franca Stagi, photographed every type of tree found in Italy, and then made dazzlingly precise quill pen drawings of each one. The result is an oversize volume called The Architecture of Trees, first published in 1983, that’s mind-blowing in its level of obsession.

In truth, it’s easy to understand why architects throughout history have fixated on trees, envying them for their strength, flexibility, graceful strategies for managing wind, and their incomparable beauty. They are like buildings, but much, much better.

The current version of tree obsession may be best represented by an apartment complex that Adjaye Associates proposed for Toronto’s Quayside project, originally (and controversially) planned as a “smart city” but repositioned as a green one. The complex, called Timber House, will be constructed from mass timber, an engineered-wood product that can be a less carbon-intensive alternative to steel and concrete. (Quayside’s developers are currently refining the design with Adjaye Associates’ New York office without the involvement of its founder, David Adjaye.) And, if you believe the first renderings, the project will have trees everywhere: on balconies, rooftops, and outcroppings.

Heatherwick, meanwhile, recently completed 1000 Trees, a Shanghai shopping center that his website describes as “two tree-covered mountains.” Renderings show a long, low building resembling a pair of hills, generously spiked with columns. These columns are not structural—they’re not there to hold up the building—but they are topped with concrete “tree pots,” rigorously configured by the engineering firm Arup to hold a single tree apiece.

The signal that the tree-filled renderings send isn’t subtle. Rather, they proclaim, “This building is combating global warming; it is green, literally and figuratively. It is not part of the problem, but part of the solution.”

That’s not a bad message. Because buildings currently generate about 40 percent of the world’s carbon emissions, there’s tremendous incentive to change how we build. And, generally speaking, planting trees (and preserving existing forests) is always a good idea. It’s one of our best weapons against global warming. But are the tree-covered buildings a realistic way of dealing with the crisis, or are they simply a stylistic tic, or worse, a form of greenwashing? Expert opinion on the subject, I discovered, is a very mixed bag.

“What I find is that the renderings are aspirational,” says landscape architect Signe Nielsen, a founding principal of MLNA. “Then, when a landscape architect is hired, there’s the hard cold reality of whether or not the structure can take the load. Can the trees be watered and maintained? And has a species been selected that won’t blow off the roof?”

Nielsen should know. Her firm did the landscape design for Heatherwick’s Little Island and oversaw the hard work of planting a stand of massive “hero” trees on a faux landmass. Nielsen, who returns weekly to oversee its maintenance, thinks the trees of Little Island are doing well, having survived 80 mph winds and other severe weather, although she recently had to replace one. “But that’s more about the soil staying in place than the trees themselves,” she says. “The cabling system of the root balls has proven to be incredibly effective.”

New York landscape architect Martha Schwartz is more critical. “It’s bullshit!” she says when asked about the tree-filled renderings. Schwartz believes that landscape architects are the professionals best equipped to beat back global warming and is leery of the ways that building architects specify trees. She’s convinced that what’s really needed is to replace urban streets with “linear forests,” like the High Line, but at grade.

By contrast, Danish landscape architect Rasmus Astrup, a partner and design principal at the Copenhagen based firm SLA, is quite upbeat about the presence of trees atop buildings. His firm supplied the greenery for the park and ski slope atop Copenhagen’s waste-to-energy power plant designed by the architectural firm BIG. And it’s deeply involved in Toronto’s Quayside project, which, in addition to tree-centric buildings by a number of architects, will have its own two-acre “forest.”

Astrup tells me that one of the reasons we see trees on buildings is that “buildings need to take responsibility. They actually need to perform a bit like the landscape or the potential landscape they’re occupying in the city. It’s about making a contribution with the building.”

Astrup is right. Buildings do need to make a contribution to their neighborhoods, their cities, and the environment overall. But the current fad for decorating buildings with living trees feels like the type of change we make when we don’t really want to change … you know, like electric SUVs.

For one thing, there’s the matter of longevity. Among those thinking about trees and time is the New York architecture firm SOM, which has been promoting an invention it calls Urban Sequoia. It’s a conceptual building that aims to “absorb carbon like trees do.” This “sequoia” is a complex assemblage of systems and techniques including using materials that have less embedded carbon (such as “hempcrete” instead of concrete), employing a variety of approaches to energy efficiency, and incorporating technology that will actively remove carbon from the atmosphere.

One intriguing aspect of the proposal is that the Urban Sequoia can, in theory, be easily reconfigured and adapted for new uses. SOM points out that this flexibility could give these buildings 100-year life spans—a long time by the standards of modern office towers—thus forestalling the carbon-intensive process of demolition and replacement. Real sequoias, of course, can live for thousands of years.

Bill Logan, a New York City tree maven who founded his company, Urban Arborists, 30 years ago, suggests that if you’re planting trees atop buildings, you should use species that don’t grow fast, like a river birch. But, he continues, trees planted on buildings will likely have to be replaced every decade or two.

Nielsen, looking at Heatherwick’s trees planted atop columns, judges that, in five or ten years, the concept will fail: “I think the trees either are going to break those pots apart or they will be stunted.”

If a tree doesn’t have the time or the room to grow, is it still a tree? Is it a full participant in the urban ecosystem, or is it more like an accessory? Astrup argues that even a tree that survives a mere decade has “had a meaningful life. It was part of the biodiversity, and it was a home for insects.” It’s a lovely sentiment, but one that ignores the fact that trees atop urban buildings are susceptible to the same problems that plague other building components: neglect and lack of maintenance. They don’t die so much as they are killed.

It’s instructive to put the architectural renderings aside and go look at actual trees. In my part of Brooklyn, many of the street trees appear to have been around for at least a century and they’re treated almost like shrines, carefully tended and protected by their nearest neighbors.

And then, in Prospect Park, Central Park, and dozens of others around the country, there are the trees planted by Frederick Law Olmsted himself. Photographer Stanley Greenberg spent the pandemic years tracking down and photographing those trees in parks across the northeast. He published them in the 2022 book Olmsted Trees. “I went out and I photographed a few of them,” Greenberg says. “Then I started thinking about how they fit what Olmsted always talked about, which was that he was designing things for a hundred years from now.”

The trees Greenberg chose are exceptional not just for their age and size, but for the power of their presence. They are monumental. What’s hard to see when you look at Olmsted’s trees in Greenberg’s photos or in person is that they were originally every bit as alien to their surroundings as the trees you see in architectural renderings.

Lacking a crane, Olmsted’s team invented a “tree moving machine,” essentially a horse-drawn wagon with a well big enough to hold and transport a substantial tree. What Olmsted knew instinctively is that, in order to simulate a “wild character,” trees needed to be planted in well-considered groups. In an 1871 letter to a park inspector, he wrote: “As a rule, each tree should be a perfect specimen and well balanced, and each group is to be regarded from all sides. In respect to the composition of the groups one with another the general effect of the broad landscape […] is of the first importance.”

As it happens, Olmsted’s aesthetic and philosophical instincts align perfectly with what science has lately discovered about trees: that they support one another with nutrients, water, shade, and, maybe, advice. As the scientist and author Simard realized early in her career, “cooperation not competition” is key to survival. But it’s not just that science has caught up with Olmsted’s predilections; it’s that he was consciously planting for future generations.

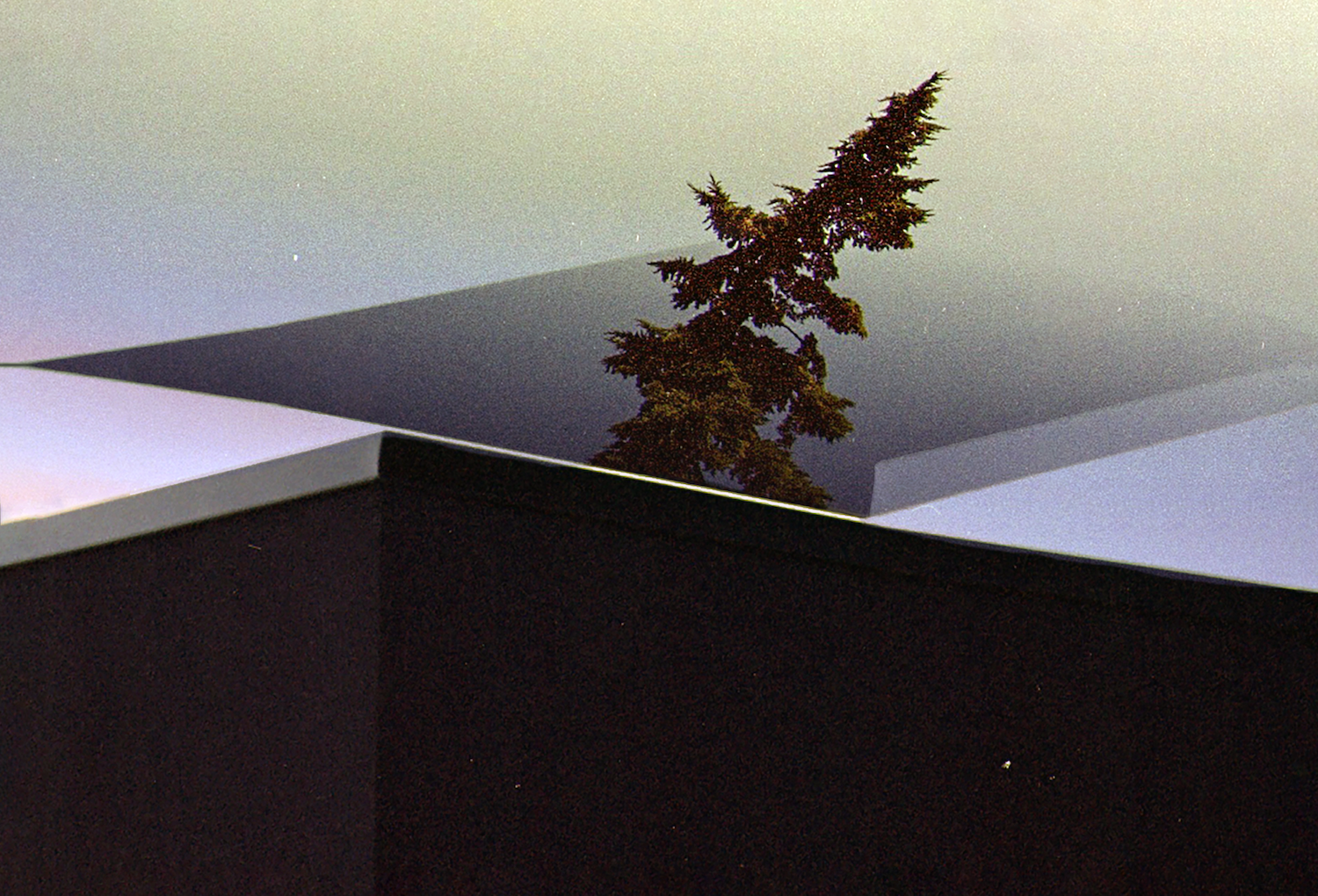

Perhaps the most startling aspect of Rosenkranz’s “Old Tree” is that it rests atop a dark metal plinth, its roots dangling nonchalantly over the side. Her tree is conspicuously, outrageously impermanent. This gesture reads like a critique of all those tree renderings, nature’s gig workers, doing temp jobs on urban rooftops.

To me, the tree renderings represent the kind of short-term thinking that got us into the global warming mess in the first place. The real way to fill our cities with trees—like the genuine solution to any urban problem—will be politically and economically challenging. It will require reapportioning the pavement, rethinking what sorts of contributions we can expect from our buildings, and radically transforming the way we build and use just about everything.