Trained as a weaver in the 1960s, Charlotte Johannesson recognized the connections—both formal and conceptual—between the loom and the computer early on. An innovator in the mediums of textile and digital art, the Swedish artist, 79, has since developed an idiosyncratic dialogue between the two tools that blends physical and digital craft to surprising, and often clever, effect.

An exhibition at England’s Nottingham Contemporary gallery (through May 7) brings together Johannesson’s practice from the past 50 years, spanning weavings, computer-made images, plotter prints, screenprints, and paintings. “I’ve always been really taken by Charlotte’s work,” says chief curator Nicole Yip, who organized the show with assistant curator Niall Farrelly. “What felt incredibly rich to me was its relationship between craft and technology. I was also completely fascinated by her story: a woman whose work has pretty much remained unacknowledged within artistic institutions for most of her life.” The retrospective in Nottingham continues a recent blossoming of interest in Johannesson’s efforts, including a solo show at Madrid’s Reina Sofía museum in 2021 and an installation at the Venice Art Biennale in 2022.

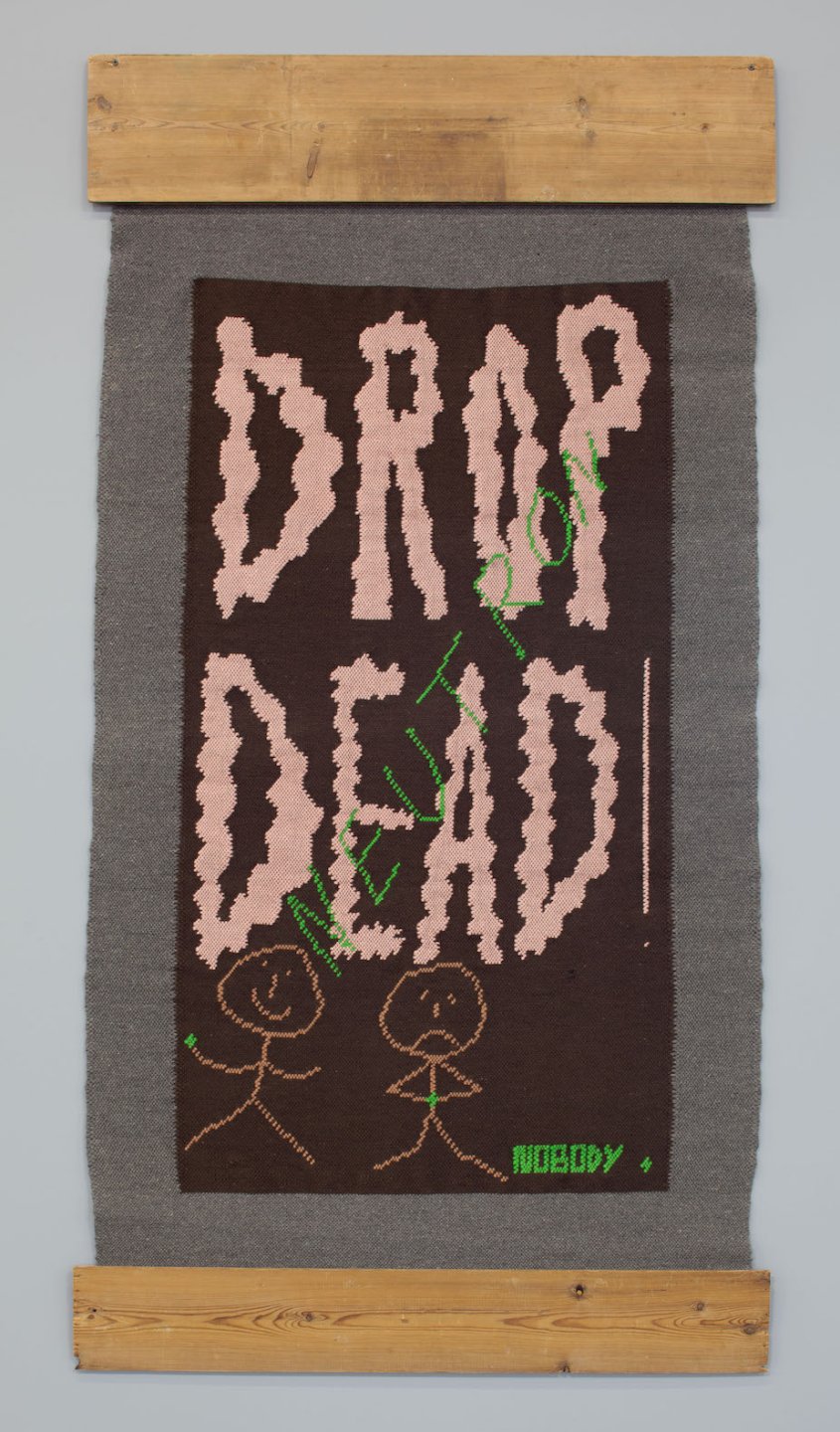

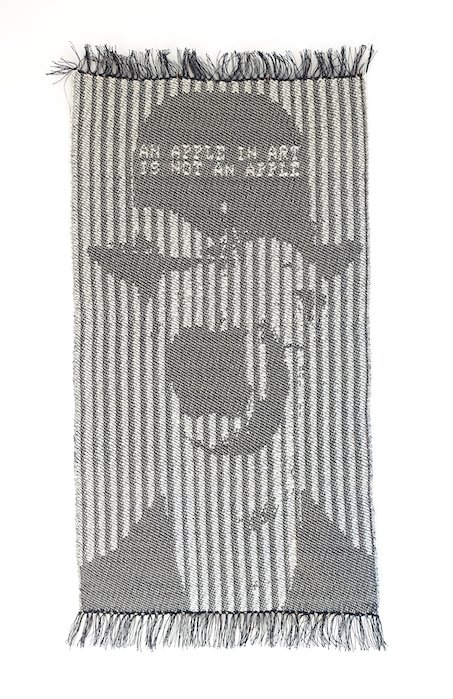

Johannesson’s early weavings, made on vertical looms, used craft as a medium for counterculture, protest, and satire, integrating political or provocative slogans and imagery reflecting what was going on in the world around her—something of particular significance to the artist and to the history of weaving, which was widely regarded as a decorative pursuit done exclusively by women at the time. (Johannesson often cites the work of Norwegian weaver Hannah Ryggen’s allegorical tapestries, which condemned violence in the midst of World War II and the Vietnam War, as a prime inspiration.) Feminism, punk, and the activism of the 1970s formed her initial output’s thematic backbone.

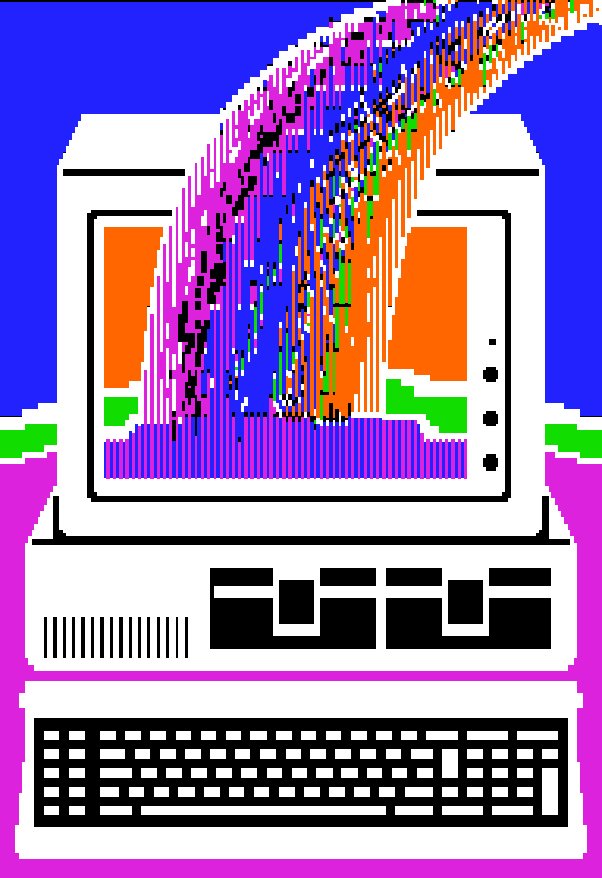

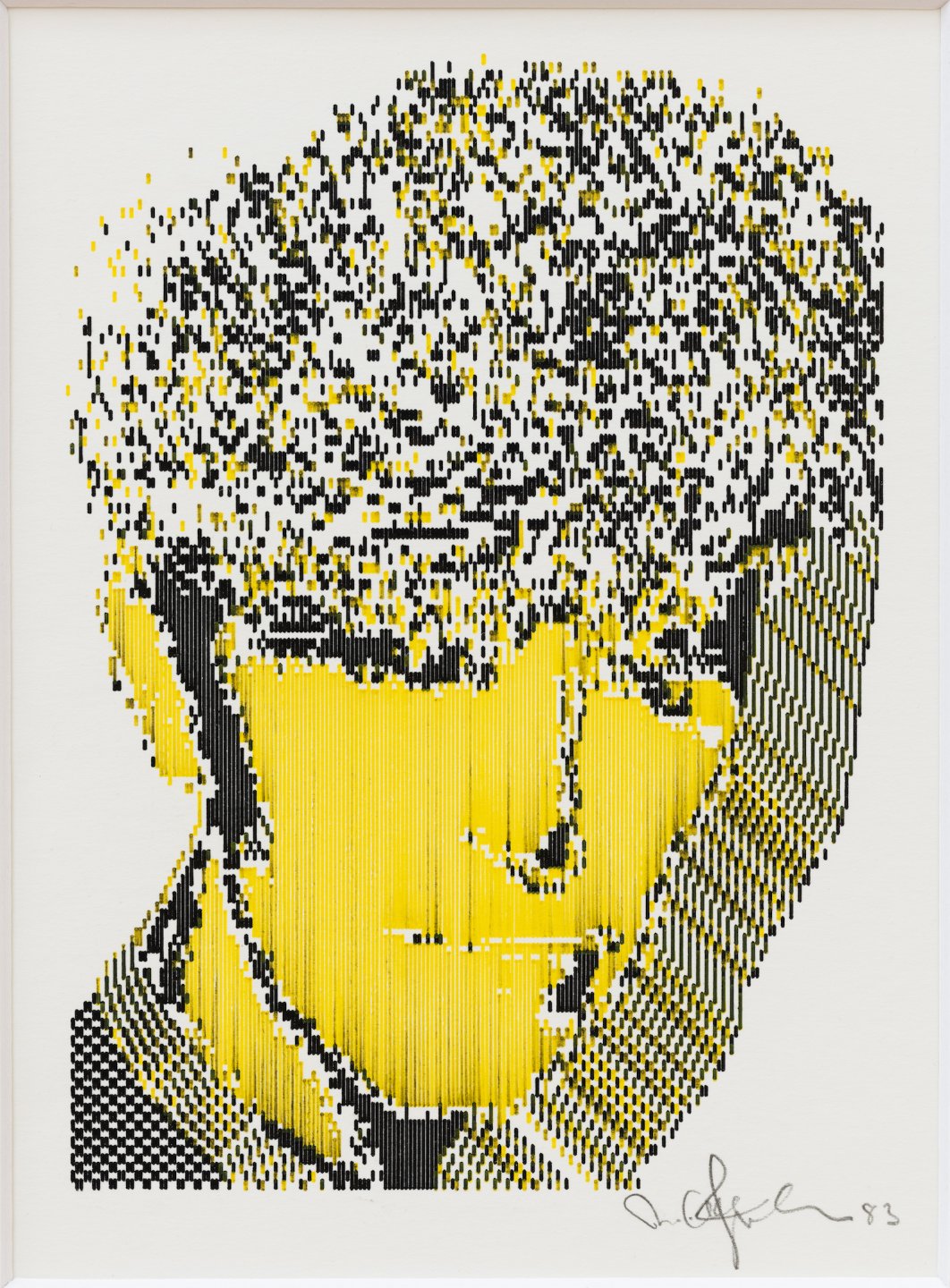

She planned her textiles on graph paper, plotting them out in squares, an approach not so different from the way images were coded on early computers. In 1978, Johannesson decided to give away her loom to a stranger in exchange for an Apple II Plus, an early version of the personal computer. She taught herself to program, coding her designs pixel by pixel. “If you wanted to use a computer to make images back then, you more or less had to figure everything out for yourself,” Johannesson said in 2012. “It all took a very long time—not unlike weaving.” It was indeed this “slow labor” of early digital image creation that particularly interested Johannesson, says Yip, and connected the process to her craft.

There was also a “synchronicity,” as Johannesson put it, between the computer and the loom: “On the computer there were 239 pixels on the horizontal side and 191 pixels on the vertical side, and that was exactly what I had in the loom when I was weaving.” Technology fascinated her and frequented her creations, in which images of computers recur throughout.

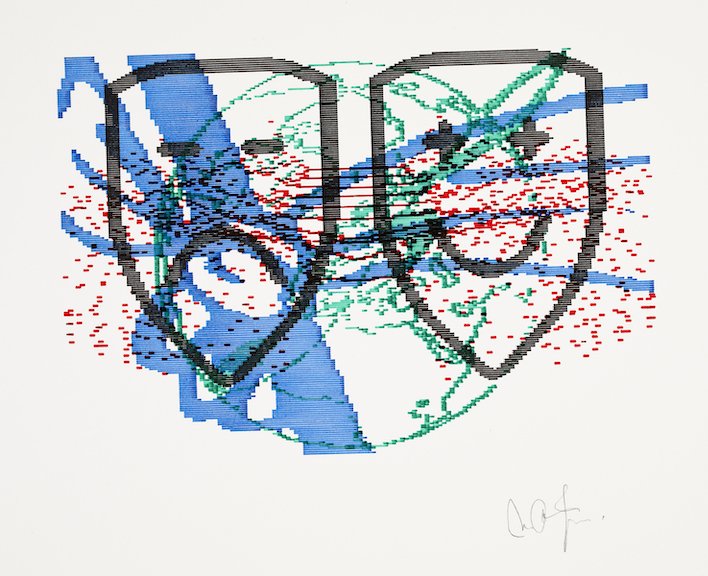

When Johannesson started using the Apple II Plus, Yip says, computers were “instruments of the techno-patriarchy. For a woman to broach that domain and find her own way—that message is still incredibly relevant today.” Johannesson was one of the first people to use a computer as a creative tool to make images, and used a plotting machine—which wields a pen or other writing tool to draw lines on a surface instead of multiple dots, as traditional printers do—to translate some of these digital images onto paper, echoing her woven forms, which took a backseat during this period. “Even though she was making computer graphics, there’s still something incredibly crafted in the quality of the image,” Yip says.

In 1981, Johannesson and her husband, Sture, an artist with a keen interest in digital technology, established the Digital Theatre, Scandinavia’s first digital arts laboratory. But when that closed, in 1985, largely due to lack of funding, she stopped creating digital images. “By this point, technology had changed,” Yip says. Apple had launched a closed graphical interface that enabled people to make their own visuals; the slow labor Johannesson prized was lost. “It wasn’t so interesting for her anymore.”

More than three decades later, Johannesson returned to her digital and physical tools with new intensity. In 2019, in collaboration with Danish graphic designer Louise Sidenius, she began to produce versions of her earliest computer images in woven form using a digital loom—a high-tech blend of a hand loom and an industrial weaving machine that uses software, such as Photoshop, to produce patterns that users can alter during the weaving process—coming full circle. She explores new ways of mixing her mediums, such as printing digitally rendered designs on handmade paper or knitting digitally inspired forms into lace. The result is a continual rethinking of what craft can be, in terms of purpose, process, and output.

We recently asked Yip to talk about pivotal pieces from Johannesson’s oeuvre, some of which are making their debut in the Nottingham Contemporary show. The anecdotes she provides shed light on the ingenuity, experimental creativity, and “punk attitude” of this septuagenarian artist, finally receiving the recognition she deserves.