In the summer of 2007, I got on a flight paid for by a magazine to travel from my home in Brooklyn, where I had recently torpedoed my life, to Seattle, where I would meet an artist, or maybe an architect or maybe a designer, named Roy McMakin. I hadn’t heard of Roy, which doesn’t mean much—I’d just started writing about architecture a few years earlier, and was mostly only aware of designers who had publicists, who were based in New York, and who took me to lunch. But I was excited to write about Roy. It was validating to be flown somewhere, and I felt optimistic that my career wasn’t over, even though, a few months earlier, I’d published a story in The New York Times that had required two corrections, which I thought—believed—made me unemployable, and also, unlovable.

Before flying it seems like I must have gone to the back room of the Chelsea gallery that was then representing McMakin (he wasn’t yet Roy, to me), and paged through books that had been handed to me, and seeing immaculately constructed chairs and tables, often bisected with paint, and dressers that I couldn’t understand but wanted to think about. McMakin, now 67, had done three shows for this gallery: one a “complete residential environment,” one named after his mother, Lequita Faye Melvin, and based on “memories of his grandparents’ house in Oklahoma,” and one that, to my mind, and maybe also to his, about the heartbreak and the beauty of trying to fit things together.

The latter was reflected in the exhibition “For,” in which McMakin, among other moves, combined found furniture with new sculpture, creating pieces made half of the past and half of the present, and it was everything to me, a person who had just realized that I had a past that was intruding onto what otherwise could have been my present. Though in writing this, I realize that “For,” in that moment, hadn’t yet happened. Not that the detail matters.

My practice then and now involves preparing as little as possible before interviewing someone. I always want to come fresh, and open, and maybe I saw those books after I first saw Roy in Seattle (my past with him, and how it all began, and how it is now—he is my friend, my favorite artist, my subject, my collaborator, my interlocutor, and my wise, slightly elder—is so mingled with the chaos of that time in my life). I didn’t realize basic biographical facts, such as the fact that he founded the handmade objects line Domestic Furniture in San Diego, in 1987, and officially opened it as a showroom the following year in Los Angeles, where he lived in Larchmont Village, where tonight my daughter and her father and some friends and I will go out to dinner. Or that he later started the firm Domestic Architecture, or that he had continued to produce fine art that looked like architecture, furniture that operated as art, and art that felt like a house. I didn’t realize that I would think about Roy’s work for—at this point—the rest of my life. Instead, given what was, as they say, going on for me, I thought, How little can I get away with?

I was supposed to write about a house designed for an art-collecting couple, whom I thought at first had hired Roy to design their house, a phrase that’s really doing the bare minimum here. What they did, or what I came to see, was that they had commissioned Roy to do a piece for them, and the piece happened to be—or had to be, or could only be—in the form of a house: a complete residential environment, overlooking Lake Washington.

During that trip, Roy picked me up from wherever I was staying and we drove to the house. At first it seemed sort of normal, a mix of Victorian and craftsman (not that I know anything about either of those styles—not my century). Inside, I realized there was something else going on.

I had been writing about nice houses for long enough by then that I had a routine, which is likewise followed by many design journalists: I would ask about what the clients wanted, and then about what ideas were embedded into their home, listening while feigning a sense of curiosity and delight. But here I was out of routine. I was curious. I was delighted. The house itself was both open and delineated; rooms at once swept into each other and separated themselves. There were tables angled together and plushly upholstered chairs that looked like things my Corvallis-based, then-alive grandmother would have had, but tweaked, somehow, into furniture that made you look twice if you looked hard enough the first time to detect something was just slightly unexpected.

In the primary bedroom, two windows were right next to each other. One had small frames that opened, providing an obstructed view of the lake that offered the capacity for transformation, and one was embedded in a single large frame, and inoperable: no visual obstruction, but no fungibility. The wife had wanted one style and the husband another; Roy had found a way to both draw attention to these differences, and to soothe them. It all exemplified how everything in Roy’s world, it seemed, was ratcheted up to the nth degree of execution, and also, I would come to learn, of emotion.

That night, the owners took us out to dinner and maybe they invited me, or maybe I invited myself, but somehow I ended up sleeping in the guest wing that night, in the lower level of the house, in a room that was delineated with at least two paint colors that cut through the bed, ran through the bedside table, and made the entire room a work of art by drawing attention to things I had never thought about, like beds always being one color. As I went to sleep, I thought about the room as a work of art, the way in which the bedside table was two colors, and how that evoked inclusion and exclusion. The next day I flew back to New York. I wrote my piece, giving it my best instead of my least, and it was published and life went on.

I figured that I would never see Roy again because that was the nature of this kind of assignment. But that is not what happened. We kept in touch. It was probably Roy, whom I’ve learned is very good at keeping in touch. One of my favorite things about him is that when I send him a text message he responds with a phone call, usually within two minutes.

Roy came to my wedding. Later, I talked to him about my divorce. He did a book event with me in Berkeley, when I’d just started grad school and published my second book, about nature and architecture, in which I included that Seattle house. He moved to San Diego, where he built an extraordinary collection of works of art—a house, complete with his furniture, for himself and his husband, Mike; a complex of rentals. After a while, I figured out that he was no longer tied to Seattle. Sometimes I would ask him if he missed that city. Eventually he would graciously say, “Well, it’s been a long time,” which reminded me that a lot of time had passed, and that we were still in conversation.

I want to tell you about Roy’s work, but at the same time part of me wants to keep it to myself, which is fueled by my inherent selfishness, which isn’t the vibe. Roy is generous. His work is generous. And his capacity and imagination to distill the weird, stupid, awful, wonderful, extraordinary fact of being alive into three- and two-dimensional forms is astonishing.

I will tell you that in his house, right now, there is a room in which there are eight dressers, four for Mike and four for Roy, all slightly different. On one of the dressers—one of his—is a series of objects he has collected, silently resting there. They made me think about conversations we’ve had about his work and how little there often is to say, because there is just so much to feel.

For instance, in 2008 he made a piece called “Untitled (a small chest of drawers with one drawer that doesn’t fit).” It’s a maple dresser, with five drawers, and one of them doesn’t fit so it sits on top. The piece, to me, is wrenching. It reminds me of all the times I didn’t fit, and also all the times I assumed I didn’t fit but maybe actually did.

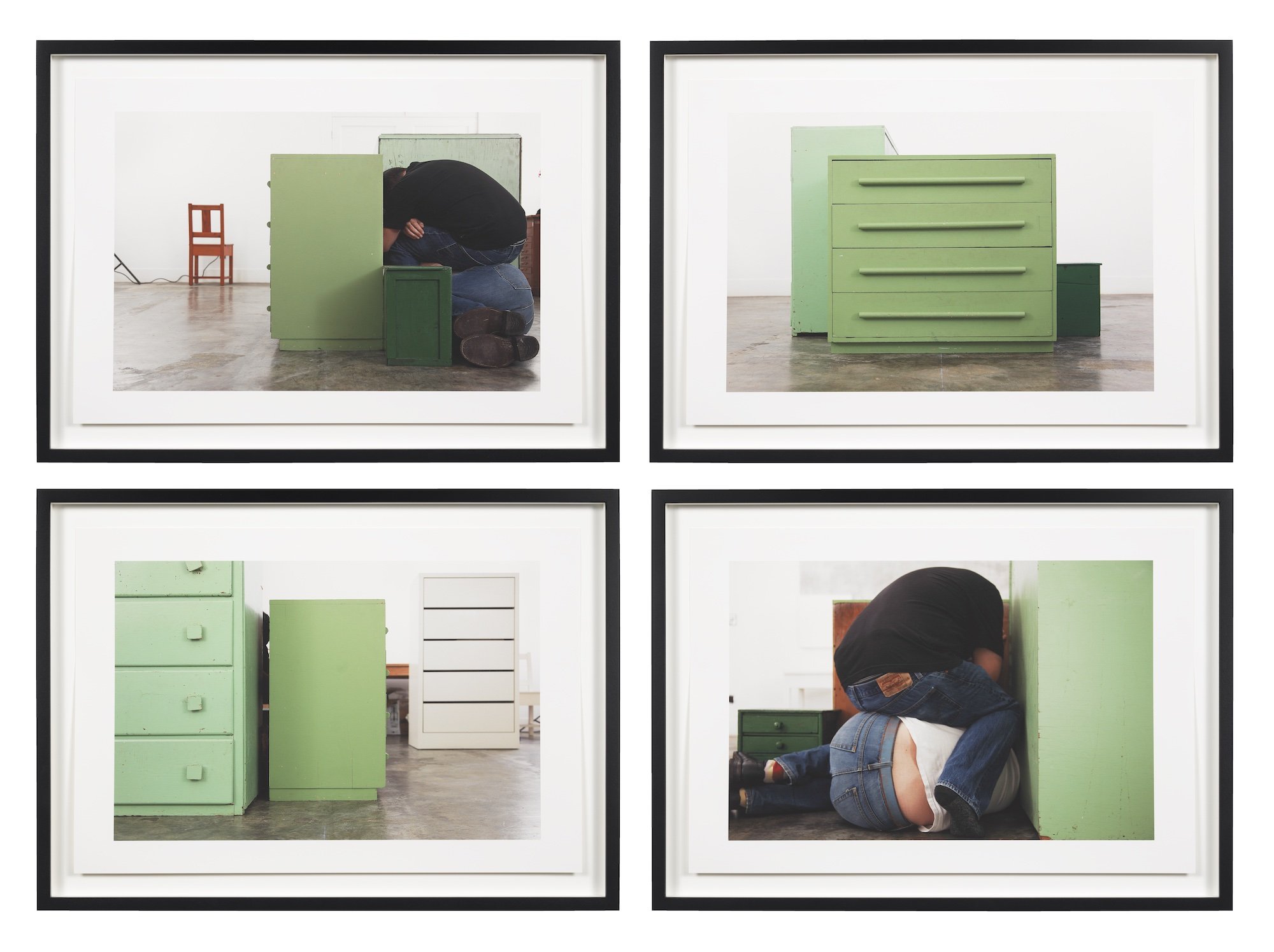

He made another piece, called “4 photographs of 4 sides of a green chest of drawers (cameras the same distance from each side) with Mike, and another green chest,” in 2011, which is a grouping of four photographs, two featuring himself and Mike, crouched together behind chests. To me, it’s about Mike’s love for Roy, and Roy’s love for Mike, and Roy’s desire for other people to get to feel the kind of love that he feels for Mike and Mike feels for him, and also the way in which dressers, for him, became love. The dressers are central to these photographs; Mike is central to these photographs; Roy is central to these photographs. That’s why I keep thinking about his work.

Another piece, “Untitled” (this one with no parenthetical subtitle), from 2018, and from the same Garth Greenan Gallery show as the photographs, is an enameled maple dresser, white, six drawers. At first blush, it’s plain, and I think maybe it’s about the craft of maple or the process of enameling. Then I realize that there are no pulls on the drawers, that I don’t know if they can open, and that it’s unlikely that they’re push drawers. And so the functional dresser becomes a sculpture and the object asks me to look at it differently, to consider volume and form and ridge and edge line. That is another trick of Roy’s heart: to invite us to glance, and then to look, and then to really, really look.

By now you have probably realized that dressers, and chests, are a large part of Roy’s work. When I asked him why that is he said that, when he was younger, he found solace in dressers. Furniture became an object onto which he could imprint his love: the love he came here with, the love we all show up with, the love that gets torn out of us or slowly leached out of us, the love that maybe we want, or at least, that I want.

When I asked him a few years later to talk about that again, because I felt like I was the opposite—I have lost so much physical material in my life; I have decided not to care—he talked about his work being more than a chance for him to imprint his own love. It’s a chance, he said, to give some of that love to someone else.

The way he sees it, or maybe it’s just the way I see it and have imprinted onto him, is that it isn’t only about the dresser he loved. It’s about how he loved that dresser and getting someone else to love a dresser, too. Or it’s about feeling loved by a dresser, by the fact of it having been made by someone. We are all alone and we are all loved.

Roy’s work is what they used to call “deceptively simple,” though there is nothing deceptive about it. Actually, it is so honest and so direct and so straightforward that it is almost too much to process, too hot to handle. To be honest, I thought about how simple I could make this story. Part of me thinks that I have not told you enough about Roy. But when I told him I was writing this and asked if he wanted to be involved, he said maybe for fact checks, sure, but that this was my thing, and that’s the thing. One of the things.

Roy performs very little on the surface and accomplishes multitudes beneath it. He talks about love, and collecting crap, and art, and how much he loves Mike—he loves Mike, so much—and within that simplicity and that clarity comes the oceanic feeling. When I talk to Roy, and when I think about his work, I am often overcome because there is so little to hold on to that I am overwhelmed. His work reminds me of all the pain that I have experienced and all of the love that I have been given next to that pain. It shows me that even in my solitude, I am not alone. That particularly in my loneliness, I am not alone.

I love Roy’s work and I love Roy. Sometimes people say they love someone when what they really mean is that they think they’re fine, or that they met them one time, or that they know they’re supposed to say that about them. But really, I love Roy. And maybe in many ways this whole essay is just an attempt, by barely glancing across the surface of what I could say, to show what this one love has looked like. How it has felt.