“We don’t receive many awards,” says Pier Vittorio Aureli, taking to the lectern at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) alongside Martino Tattara, with whom he founded the architecture practice Dogma, in 2002. Dogma was the recipient of the 2023 RIBA Charles Jencks Award, which is named after the late influential theorist and architect Charles Jencks and that is awarded annually to architects for making a significant contribution to theory and practice in architecture. Alongside a £3,000 (about $3,800) cash prize, the winners are invited to give a lecture.

And a Dogma lecture is a hot ticket. The partners have built almost nothing in their 22 years of practice, yet can pack the institute’s auditorium with thirtysomethings in technical sneakers and trendy workwear, as they did on a rainy evening this past May.

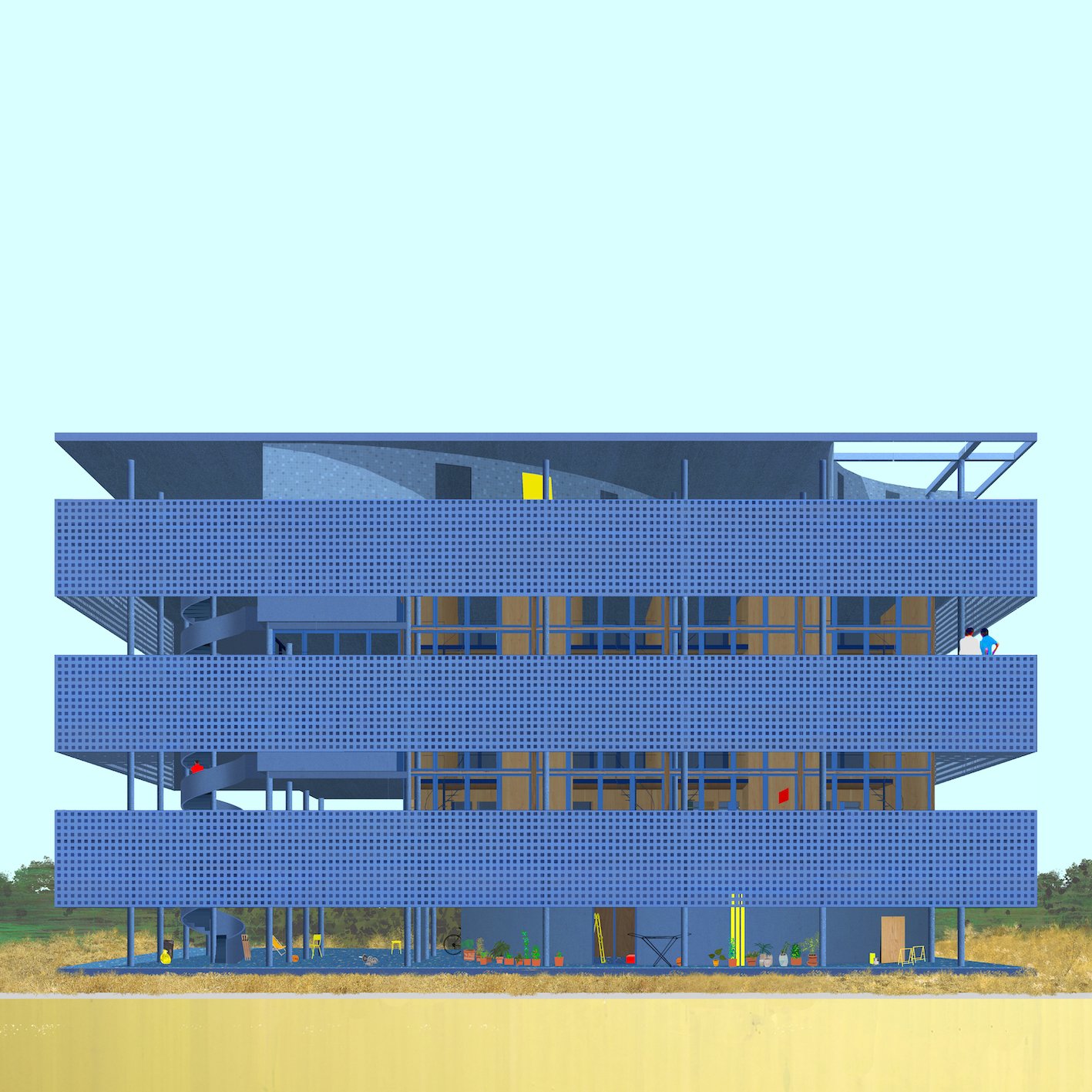

The lecture flows out of them like an impassioned exhale. Rather than a career retrospective that might befit such an awards ceremony, the pair give an in-depth analysis of the urban villa— and its history as a multifamily housing typology—leading to Faux Corbu, their own reinterpretation of a Le Corbusier project, produced for an exhibition in Tunis. Historical research folds seamlessly into Dogma’s design proposal, its technical details (floor plans across six floors, wall and structural core placements) comfortably explained in relation to the building’s social implications (shared spaces that will bring together the villa’s various imagined social groupings). Aureli is full-faced and animated; Tattara, tall and slender, is more nonchalant. He leans back and checks his watch while waiting his turn to pick up the narrative thread. Both speak from memory; there’s not a note in sight.

“Everything we do, we do always together. There has never been a division of labor between us,” Aureli says via video call a week or so after the RIBA lecture. The pair met in Venice in the late 1990s before moving to Rotterdam and later Brussels, where the office is still based.

Today Dogma occupies a peculiar place in the European architecture scene. Its principals are well known and well liked—they are rigorous researchers, politically forthright, and produce projects steeped in architectural history. Yet the vast majority of their work exists in the form of drawings and texts in books, exhibitions, and online. “We never thought, and we don’t think, that Dogma is a paper architecture practice. In our projects, we really think architecture is about building,” Aureli says. “We don’t want to build at all costs, though.”

If not uncompromising, then Dogma’s approach to architecture might best be understood as unflinchingly critical. All of their dozens of works seem to take seriously the meaning of the word project as in “throw forth”—in the sense that they propose ideas that critique an architectural, urban, or otherwise built status quo. Characteristically precise in his choice of words, Aureli describes this as “a tension with what exists and what goes on,” but is reluctant to describe the practice as explicitly political, citing the limited impact an architect can have on “serious structural problems.”

Housing is the serious structural problem that has most consistently occupied the attention of Dogma, as evinced in projects exploring various housing typologies in considerable depth, including the single room (Loveless, from 2018) and cooperatives (Do you hear me when you sleep?, from 2019), up to megastructures for 16,000 inhabitants (Live Forever/The Return of the Factory, from 2013). That European cities face multiple scales of housing crisis does not need repeating, yet Dogma’s engagement with the specifics of the problem—unaffordability, social isolation, lack of green space—reflects both a respect for residents and the limitations of the role of the architect confronting these concerns.

For example, Do you hear me when you sleep? and Do you see me when we pass? (2019) are collaborations with community land trusts in London and Brussels, respectively. The projects are materially lightweight, with simple engineered timber structures to allow residents to self-build and to accommodate “all the seasons of life”—meaning that they are easy to internally reconfigure according to the needs of various domestic groups. Similarly, Faux Corbu features a communal kitchen and rooftop terrace, as well as generous balconies extending from each floor. All three serve as prototypes, not just as what Dogma’s website describes as “beautiful one-off villas,” but as case studies “towards a more general idea of housing.”

What use are these projects, you might ask, if they exist only on paper—if no one can live in them?

There is a considerable gulf between what an architect can imagine and what can be built in an economic system that is market-led but that treats housing as a commodity rather than an inalienable right. And yet Dogma’s persistent, rigorous work may well play a role in narrowing that chasm.

Aureli describes “incredible efforts in the field of housing” over the past five years, naming two Barcelona-based practices—Lacol and H Arquitectes—as ones that have managed to construct exemplary social and sociable housing projects. (Aureli is too humble to claim any direct influence from Dogma on these projects, but it’s not hard to at least see the spirit of Dogma in Lacol’s La Borda or H Arquitectes’ Social housing 1737.)

“It feels good that what we thought ten years ago, which sounded very counterintuitive, now is becoming something which also produces real stuff,” Aureli says. “Ten years ago, even to mention the words ‘public housing’ would put people in a disbelief mode. Now I see politicians, not even radical politicians, considering that commodified housing has been a major failure. So I think we are part of a movement that is a major political change in architecture, and I hope it can be acknowledged as such.”

Back at the RIBA hall, Aureli and Tattara round out their lecture with a Q and A, chuckling about how they were not trying to be influencers and declaring the “importance of protecting students.” Despite their critical stance, Dogma are far from po-faced or solemn. There is a warmth to their approach that can be hidden beneath the surface of their sober project drawings, but that is quickly apparent in their demeanor and their popularity with students. Both Aureli and Tattara have taught extensively and schools are arguably where their influence will have the strongest ripples, even if it is hard to discern.

There may not be many awards and there may not be many buildings, but a look back at Dogma’s career might trace a route for the future of building homes. “The benefit of history is [in] putting things in a continuum,” Aureli told the rapt audience, “giving you a sense of what to do next.”