In 1959, the year Barbie became the first adult-figured doll in America to stick an arched foot into the world of child’s play, a graphic artist named Leo Lionni reached a different benchmark of sophistication. He created a children’s book called Little Blue and Little Yellow out of nothing but torn-paper blobs.

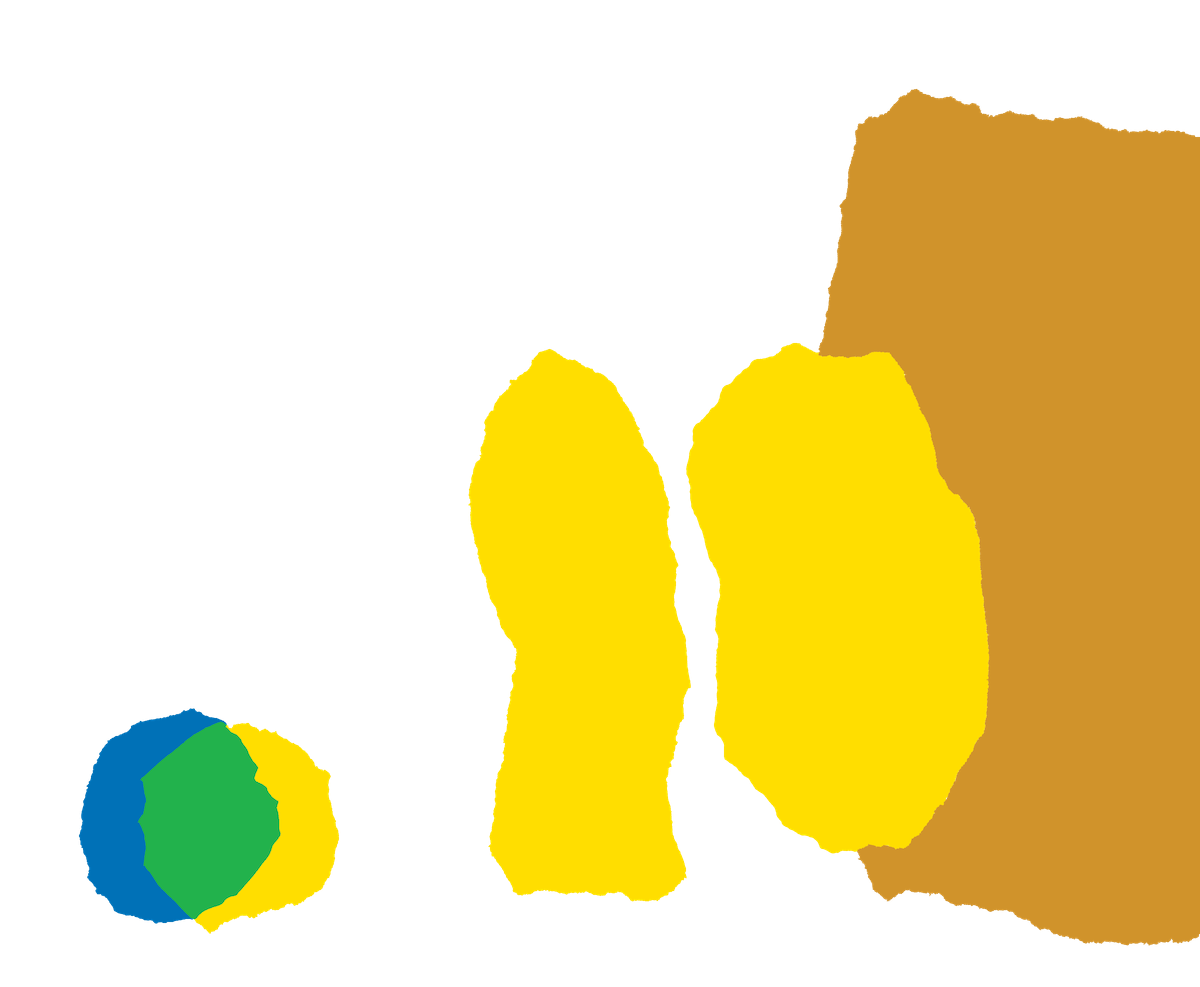

Lionni’s book, which remains beloved to this day, tells the story of two children represented as a blue blob and a yellow blob. Together, they roam a world made up of other colorful shapes that comprise family members and friends.

When Little Blue and Little Yellow hug, they turn into a single mass of green. This green blob is rejected by both sets of bewildered parents. Weeping, it dissolves into blue and yellow tears that are reconstituted into the characters’ former selves. At that point, everyone hugs and changes color.

If there is a children’s book more minimal than this, I defy you to find it. Charles G. Shaw’s It Looked Like Spilt Milk (1947) is certainly minimal, presenting rough white silhouettes of objects and creatures reversed out of blue backgrounds. But the images are still recognizable as squirrels, trees, and ice-cream cones. Shel Silverstein’s The Missing Piece (1976) is also minimal; its protagonist is a pie shape that rolls along a line representing the earth. But that character has a pinpoint for an eye. There are no eyes in Little Blue and Little Yellow. There are only lumpy forms that somehow convey through their contours and composition buildings, landscapes, joy, animation, anxiety, protectiveness, and love.

In 1959, such simplicity hit the market like a thump in a pillow fight. Ellen Lewis Buell, the late children’s books editor of The New York Times, wrote, “Lately it has seemed as if grown-ups were divided into three groups. The first, generally artists, are those who think Leo Lionni’s Little Blue and Little Yellow wonderfully clever and handsome. The second group sees it mainly as a haphazard collection of color blobs and the third, which at first included this reader, admired its ingenuity but wondered if it weren’t a sophisticated tour de force, too subtle for children.”

Buell changed her mind when she saw youngsters responding delightedly to the story and asking for colored construction paper, which they tore into shapes. “That they had just had an elementary lesson in color recognition and mixing was incidental,” she wrote. “They were having fun.”

But Buell herself oversimplified what Little Blue and Little Yellow brought to the table. It wasn’t just a lesson in color theory, but a work of avant-garde modernism that made an extraordinarily effective use of collage—the same instrument by which cubists, Dadaists, Russian Constructivists, and surrealists expressed their revolutionary aesthetics.

“Collage is the art form of the twentieth century because it’s about putting back a world in pieces,” says Leonard Marcus, a children’s book historian and co-organizer of “Between Worlds: The Art and Design of Leo Lionni,” an exhibition opening at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, on November 18.

Lionni was not the first to introduce abstract collages to so-called children’s literature, Marcus says. That distinction would probably go to the Russian artist El Lissitzky, whose About Two Squares (1922), which he dedicated to “all kids,” offers a dynamic interplay of block-printed geometric shapes and letterforms. But the narratively sparse title, with its patches and shards of color, is hardly what most readers would think of as a children’s book. Lionni was an undisputed children’s book artist who used torn paper to push abstraction further than anyone.

“He was trying to get a certain effect and he wanted to preserve the handmade quality; he didn’t want it to look cold and machine-made,” Marcus says. “He may have been the first children’s book artist in the U.S. to do it that way.“

Little Blue and Little Yellow “certainly changed the way people thought about presenting content to children,” says Steven Heller, a design historian, educator, and former New York Times art director who is collaborating with Marcus on the exhibition.

How Lionni arrived at his torn-paper medium—he would go on to publish more than 40 children’s books before his death in 1999, but would never duplicate the style—is a story with a few layers.

Born in 1910 in the Netherlands, he was an only child in a cultivated middle-class household that included a mother who was an opera singer with Dutch Christian roots, and a father who followed his Sephardic Jewish forebears in working as a diamond cutter and who later became an accountant. The large extended family included two uncles who collected avant-garde art.

“Between Worlds,” which is the title of Lionni’s 1997 memoir as well as the coming exhibition, refers to his cultural vicissitudes. He moved from Amsterdam to Brussels to Philadelphia to Genoa, all before completing high school. In each country he picked up a new language. When Hitler invaded the Sudetenland, in 1938, he resolved to leave Europe. Returning to Philadelphia, where he had spent a teenage year, he found work as an art director at the N.W. Ayer advertising agency. His wife, Nora, and their two young sons joined him once they had visas.

The phrase “between worlds” also relates to Lionni’s straddling the domains of fine and applied art. The 1940s and ’50s in America was a golden age of corporate modernism. Companies lavished huge budgets on sophisticated design campaigns to construct what was then described as their “corporate identity.” Logos such as the CBS Eye, designed by William Golden, were considered the gold standard—clean, recognizable, powerful, evocative, and abstract enough to be applied at any size to multiple environments, from business cards to billboards to television screens.

Lionni “was on both sides of the street, between commercial art and fine art, back and forth,” Marcus says. He kept a New York studio for his own artistic pursuits, while commissioning advertising and magazine illustrations from artists including Andy Warhol, Alexander Calder, Saul Steinberg, and Ben Shahn. (He also mingled with many of these people socially.) Josef Albers invited him to teach one summer month in 1945 at Black Mountain College, where he fraternized with the Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and the Harlem Renaissance painter Jacob Lawrence. In 1948, he became the art director of Fortune magazine, part of Henry Luce’s Time-Life publishing empire. He still had that job 11 years later, when Little Blue and Little Yellow came into being.

As the much-told story goes, Lionni was shepherding his two restless grandchildren, Pippo, 5, and Annie, 3, on the commuter train from New York to Greenwich, Connecticut. To distract them, he pulled a fresh copy of Life magazine from his briefcase and tried to interest them in the ads. When that failed, he happened on a blue-and-yellow page from which he ripped shapes and improvised his tale.

At home, Lionni and the children transferred the fragments to a book dummy. The next day he showed it to Fabio Coen, a friend and neighbor who happened to be the children’s book editor of a publishing company called McDowell, Obolensky.

“I didn’t take him seriously at first,” Lionni wrote about Coen’s immediate offer to bring out the book, “because I couldn’t imagine any publisher would have the courage to publish what looked like a defiant object designed to épater le bourgeois.”

If Lionni suspected that Little Blue and Little Yellow looked like a deliberate effort to shock the American middle class, he went out of his way to suggest that it was just a creative lark. In his memoir, written 38 years after the book emerged, he made the origin story canonical, and the tale of the train is now reprinted in every copy. Though an outspoken advocate for human rights throughout his life, he never dwelled on the fact that Little Blue and Little Yellow is a story of children of different colors who experience and teach their parents about harmony, literally, in the chromatic sense. Or that it was published five years after the 1954 Supreme Court decision that desegregated America’s schools, and five years before the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Is it conceivable that the book can be read as anything but a parable about racial tolerance?

Probably not, says Annie Lionni, who is now 66 and wants it known that the reports of her and her brother’s misbehavior on that train are somewhat exaggerated. The most convincing evidence that Leo had more of a political agenda than he was willing to reveal, she says, is a photograph of children of various races holding hands in a circle, which hung prominently in an exhibition that was an adjunct to the American pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair.

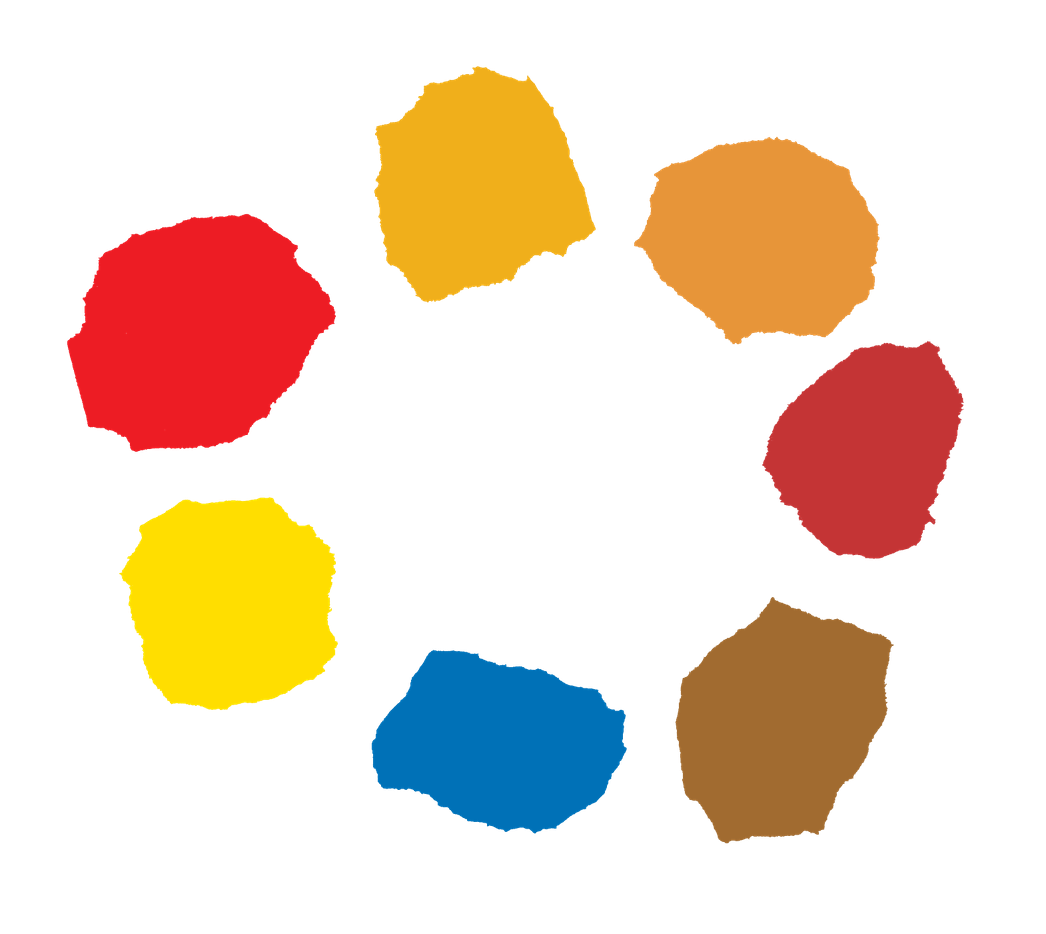

The show, called “Unfinished Business,” amounted to an admission on a global stage that the United States had, and was seeking to overcome, social problems such as segregation. Lionni designed it, and his photo of children unified in play symbolized what the country ought to aspire to. According to Annie, who supervises her grandfather’s legacy, this particular image stuck in the craw of Southern Congressmen, who found the exhibition offensive and quickly had it closed.

In 2014, Annie’s attention was drawn to an installation photo of the show that included the image of the children, and she noticed a resemblance to a page in Little Blue and Little Yellow featuring a circle of multicolor blobs. Both exhibition and book identified the game in exactly the same way: as “Ring-a-Ring-O’Roses,” a British variation of the American “Ring Around the Rosie.” She knew from a postcard her grandfather wrote to Ben Shahn that Lionni had been enraged by the senators’ interference. It seemed reasonable that, a year after “Unfinished Business” was shut down, Lionni got his sneaky revenge with a half-buried subtext in the book, celebrating racial diversity through abstract shapes. “But I made that connection,” Annie says. “This is something he didn’t articulate, at least not to me.”

Even if the parallel images represented “some kind of unintentional link in Leo’s head,” Annie went on, he was consistent in his theme of “getting along in a group.” All his children’s books—including Swimmy (1963), Frederick (1967), and It’s Mine! (1985), which he produced at a rate of at one or two almost every year for 40 years—are about “identifying a problem and making a better world,” she says. But none would ever be as suggestive of race relations as Little Blue and Little Yellow (though color is a frequent identity shaper of his characters), nor as abstract and minimal.

What seems certain is that the book was a hinge between worlds. Shortly before the train episode, Lionni produced a large-format, almost wordless publication for Fortune’s advertisers called Design for the Printed Page, which featured abstract shapes and textures presented in arresting ways, to show off the magazine’s prowess in displaying advertising. “Design is form,” he wrote in the brief, accompanying text. “Sometimes it is decorative form and has no other function than to give pleasure to the eye. Often it is expressive form, related to conceptual content, to meaning. It is always abstract but, like a gesture or a tone of voice, it has the power to command and hold attention, to create symbols, to clarify ideas.”

One can imagine Lionni putting together this modernist manifesto—um, manual—surrounded by paste-up artists gluing type to boards to prepare them for printing the old-fashioned way. It’s easy to see why he reached for the rubber cement months later when he was arranging the collage elements for his first children’s book.

But just beyond Little Blue and Little Yellow lay another country. In 1961, Lionni left New York with its modernist buildings and modern artists and returned to craggy, ancient Italy, where he devoted himself for the rest of his life to making painting and sculpture. He continued to use collage in his children’s books, but pattern and texture predominated in the figurative designs, and his characters now represented the little animals he had loved and collected in his youth.

“I found myself digging deeper and deeper into the memories of my childhood,” he wrote of this development, “and I learned to distinguish within myself that which was peculiar to my own feelings and experience and that which was universal to children everywhere. I became ever more conscious of the problems children face and the importance of the messages we send to them.”