The original sin of the vintage car “hobby” is that many owners don’t drive their cars. Survey auction house catalogs and you’ll discern an inverse relationship between how brilliantly a car was engineered and how many miles it’s traveled. The tendency to treat such automobiles as a diaper-buffed asset class rather than a singular means of transportation poses an existential threat to the pastime: If younger generations don’t see these cars on the road, they won’t be inspired to learn about them. Poof! No more car culture.

That’s why collectors like Steven Harris are viewed, both within and outside the hobby, as downright heroes. The New York–based architect, 72, maintains a fleet of vintage Porsches that are gassed up and ready to run at a moment’s whim. He’s also something of an éminence grise of high-performance 911s. His extraordinary collection of race-bred RS models has been displayed at upstate New York’s Saratoga Automobile Museum, where Harris is a trustee, and features in the new book Air & Water: Rare Porsches, 1956–2019 (Schiffer Publishing). And though his peers may content themselves by watching their toys’ valuations skyrocket, Harris would sooner ship a rally-prepped, 60-year-old Porsche to rural Asia or South America and beat the scheisse out of it.

His obsession took root in childhood, taking sensory-overload trips in his uncle’s 356 A Coupe. But over the years, Harris developed an appreciation for Porsche’s purity of line, particularly that of the 911. That quintessential sports car, with a lineage traceable to the Type 64 of the 1930s, has acted as a muse for Harris throughout his career: His namesake architectural firm, known for its pared-down yet exacting work that invariably respects its context, has designed prestigious residential and commercial projects around the globe, and Harris has taught at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, a Manhattan nonprofit architecture studio and think tank, as well as at Harvard, Princeton, and the Yale School of Architecture, where he has sat on the faculty since 1984.

Such a trajectory, it turns out, pairs well with an appreciation for rare 911s. For Harris, that model—which the German automaker has meticulously tweaked, not overhauled, since developing its streamlined design decades ago as new needs and technologies have arisen, without compromising its look and feel—doubles as a vessel for knowledge in work and in life. The 911 has taught him about the value of making perpetual, iterative improvements, and of taking the time to determine the perfect balance of power and place, resulting in elevated experiences marked by ease, efficiency, and even joy.

Here, Harris discusses how he stumbled into collecting, the intersections between his cars and his craft, and the lessons a fussy, rear-engined, analog machine like the 911 may yet hold for a culture obsessed with speed, newness, and novelty.

“My obsession with cars is probably more emotional than rational. When I was very young, my grandmother’s housekeeper taught me the names of all the cars on the road. My first contact with Porsche came at age 8, when my uncle purchased a 1958 356 A Coupe. I remember what it sounds like, what it smells like. That’s what really sparked the obsession. My dad later bought a 911 S, the car I took my driver’s test in. Around ten years ago I found a car almost identical to my dad’s car, right down to the smell. Like I said, obsession.

At the risk of sounding like George Romney, I don’t know how many Porsches I own. Let’s say it’s more than fifty, fewer than sixty. It was never my intention to collect them; after taking my dad’s 911 S to college, I didn’t buy one for another forty years. Couldn’t afford to. But coinciding with around the time I—ahem—bleached my hair white, I decided it was time to have a Porsche. The more I learned about cars like my uncle’s 356, the more interested I became in racier versions like the 356 A Carrera and 356 GT Speedster. So I got them.

The thing is, most people can’t tell which of these is super expensive or which is cheaper, which is something I absolutely love about Porsches. They don’t bling themselves out. No gold chains in the glove box. It’s only with study, and with use, that you learn what’s truly special about them.

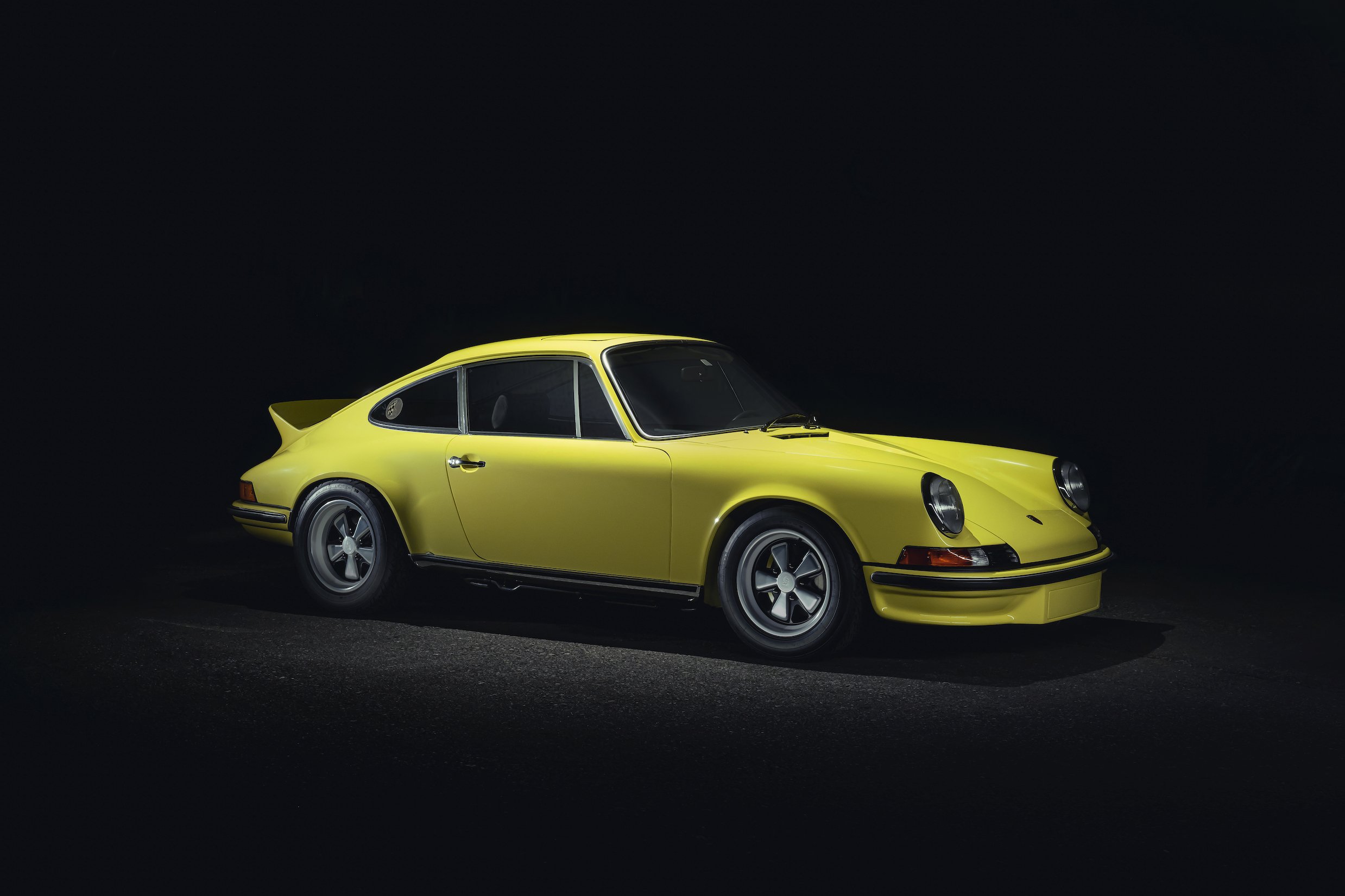

That’s what attracted me to the RS models. They’re regarded as the ultimate 911s, and the ’73 Carrera RS is the holy grail. It’s not the fastest car, but there’s a magic about it. The brilliant thing about a ’73 RS is that the chassis and the power are in perfect balance. That notion of getting the power appropriate to the chassis extends to architecture, believe it or not. There’s the balance you have to strike between accommodation, the site, and the scale of gesture. Some architects make buildings that look like exquisite pieces of sushi on a platter. There’s another approach that positions the house in appropriate scale to its site and landscape. That’s Porsche at its best: balancing power to the chassis.

Some people count sheep at night. I count cars. And because I have a [fastidious] mind, I collect things in series. They made [around] sixteen versions of the Carrera RS, and I have them all the way through. Probably the rarest of them is a 1984 SC RS. That was the model made famous by the Rothmans Paris-Dakar Rally [now Dakar Rally] car. Eleven of them were sold to teams for rallying, and nine weren’t. I have one of those nine. It has some eleven hundred miles on it.

Most people who buy these cars wrap them in plastic and never drive them, treating them as an asset class you flip. That’s a game I’m no good at. You can get into any of my cars today and drive it cross-country. I really enjoy rallying. It’s why I drove a 356 in the Peking to Paris [Motor Challenge]—though we fitted a huge metal skid plate to the bottom of the car to protect it from rocks. And boy, did it get beat up. Yet despite all the special prep and abuse it took, I can jump in that car right now and drive it to the A&P.

Another example of my fastidious mind: I’m a big fan of misremembering things, because sometimes the misremembering—the misunderstanding—is more provocative than the real thing. I remember reading Foucault. I’d read thirty pages, then I’d have an idea. It wasn’t whether I got Foucault right; it’s that it sparked a thought. That extends to my relationships with rallying and with architecture.

Turning south from Santiago, Chile, toward Ushuaia, Argentina, you drive through what feels like a petrified landscape, like everything’s been dead for fifty years. But if you get a sprinkle of rain, everything turns electric green. When you’re rallying, you don’t see features of the landscape individually or anecdotally. They string together into a continuum.

That same notion can inform how you make a building. I tend to think of a residential project starting at the curb, then there’s a piece of land, then the building, then the courtyard. But if you turn around and walk back the way you came, it’s totally different. How it unravels, the progression … that’s where the spark comes from.

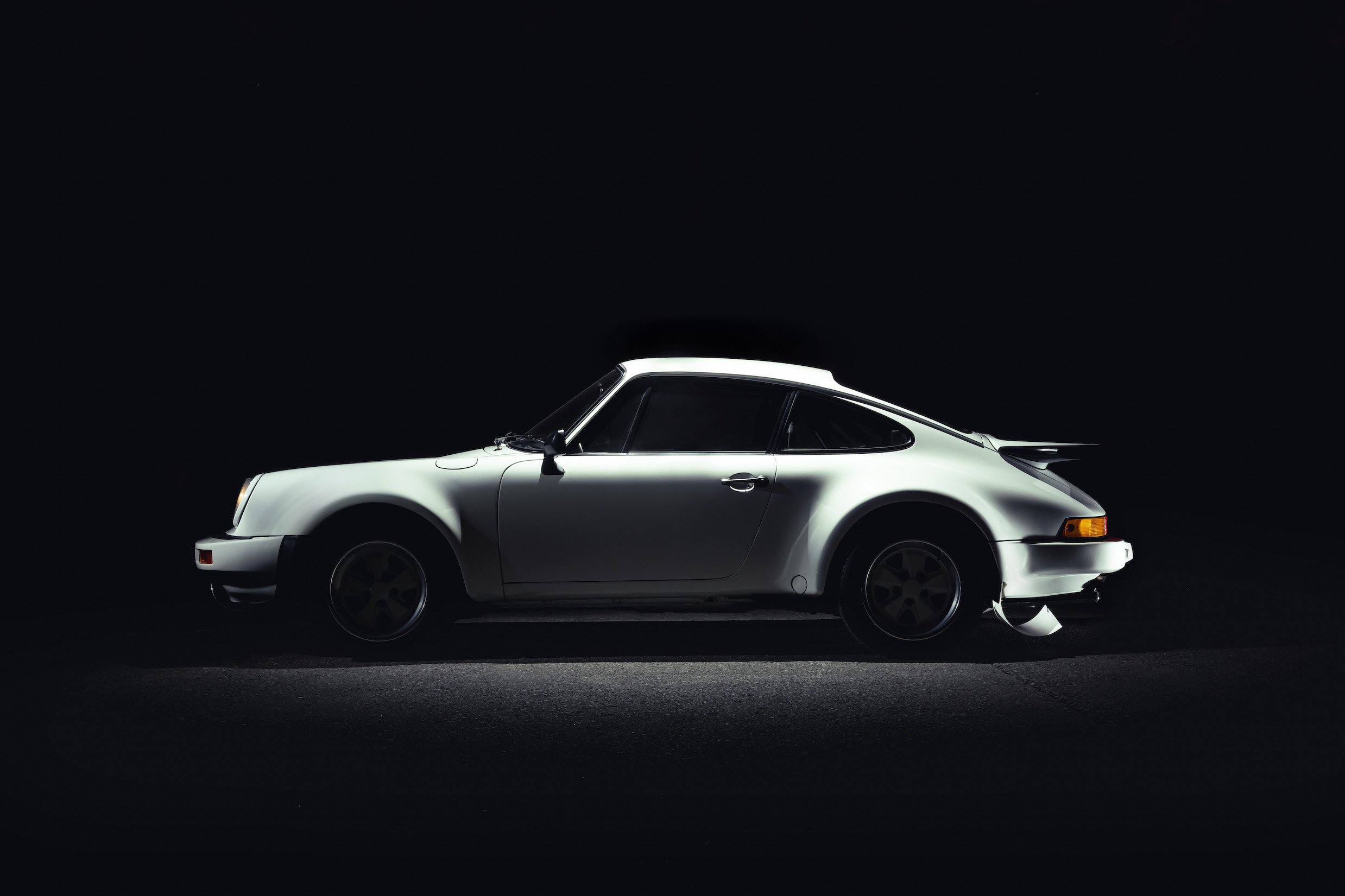

Part of what keeps me interested in these cars and these experiences—and what I think distinguishes my attitude from other collectors—is that, even though I prefer the older cars, I accept that things evolve. The purists got upset when, for example, the 1998 RS shipped with power steering instead of hydraulic steering. Well, the future has been coming for a long time. How you meet it is what makes the difference.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.