JEB (Joan E. Biren), “Self-portrait with Sharon” (1970)

“This is what I call my ‘first lesbian photograph,’” JEB says. “I wanted to see a picture of two lesbians kissing and I could not find one. So I borrowed a camera. From looking at this picture, I learned how much I wanted to see more pictures like this. That’s what inspired me to become a photographer of lesbians—a photographer, period.”

In the late ’60s, Joan E. Biren, best-known by the moniker JEB, wanted to see a picture of two lesbians kissing, but could not find one. This acute desire to see herself portrayed in an image—what the artist now calls “representational justice”—prompted her to take a photograph of herself with Sharon Deevey, her lover at the time, smiling as they engaged in the oral act of affection. It would become the first picture in her long career as a photographer of women-loving women, labia, and other totems of lesbian life.

“Self-portrait with Sharon” (1970), along with other images of lesbians kissing, sleeping, mothering, protesting, and embracing became Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians (self-published in 1979; reissued by Anthology Editions in 2021), the first book of lesbian photography ever published. JEB’s documentation of the reality of lesbian life in the United States—away from the male gaze, beyond the beauty standards of the time, and in very close community and collaboration with her subjects—articulates an idea of beauty born out of authentic representation.

In her research of queer imagery, JEB began to cobble together a conception of herself within a lesbian art-historical lineage, though one that was totally invisible, if not willfully obscured, by an exclusionary art and academic world. Wanting to bring this vision to her community, she amassed more than 400 images, taken by herself and others, compiling them into an ever-evolving slideshow she informally called “The Dyke Show” (and formally titled “Lesbian Images in Photography: 1850–The Present”) that she carted around from 1979 through 1985 in her unreliable VW Microbus, showing it at colleges, community centers, lesbian bars, and feminist bookstores, to mostly female audiences.

With each screening of “The Dyke Show,” which the photographer, now 78, describes as a “unique mixture of history, art history, stand-up comedy, and activism,” JEB serves as a live narrator, locating her lesbian audience in a lineage that, like her, they sensed but had likely never seen. “The interesting thing about knowing you come from somewhere is that it gives people an idea of what the future might look like, and how to move into it,” JEB told me. “It’s very hard to explain that. But I know it’s true.”

Although “The Dyke Show” has retained a level of cult fame among lesbians in and outside of the art world, until four months ago, it hadn’t been shown in its entirety since 1984. The occasion for its screening (complete with JEB as its host) at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center in New York, which I attended along with hundreds of excited queers, was an extraordinary exhibition, titled “Images on which to build, 1970s–1990s” and curated by Ariel Goldberg. It was first presented at the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati last fall and is now up at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art in New York, until July 30.

With the exception of a recently added introduction and epilogue, and some elisions for accuracy, JEB performs “The Dyke Show” exactly as she did nearly 40 years ago. And yet, when she gets to the introductory slide for lesbian photographer Berenice Abbott, which indicates that she was born in 1898 and “lives and works in Maine,” the whole audience gasped. (“Abbott died. Now we can say she was a lesbian,” JEB chides in the epilogue.) If she were alive today, I thought, she’d be 125!

“The Dyke Show”’s immediacy and relevance connects so powerfully to present-day queer audiences that it’s easy to forget that it’s decades old. Indeed, JEB says the most surprising aspect of the present-day reaction to “The Dyke Show” is how similar it is to how audiences reacted all those years ago. “I did not expect that,” she says. “Back then, there were no images like this in mainstream media or accessible within the community. And now we have a surfeit of images. I think that speaks to the power of knowing your history. Seeing images of queers from the nineteenth century allows people to really believe that we have always existed. That grounds people.”

I can attest that it also makes people hoot and holler, and laugh and cry, in a kind of identification-cum-futurist ecstasy. As JEB says in “The Dyke Show,” “We needed to connect to a past so that we could see a future.” In this way, the work of “The Dyke Show,” JEB says, has a lot in common with the comparison Black scholar-activist adrienne maree brown makes between political organizing and science fiction in her book Pleasure Activism: “I believe that all organizing is science fiction—that we are shaping the future we long for and have not yet experienced.”

With “The Dyke Show”—from which a selection of images are shown below—JEB and her audiences engage in a kind of science fiction that “materialized a queer world where one had not existed before.” Still, JEB is quick to point out that, although representation can create confidence and solidarity, it does not amount to material justice in the world. “It can move us towards liberation,” she says. “But it is not liberation.” “The Dyke Show” may be an unfinished gesture, but it is thrilling, and certainly beautiful, nonetheless.

Found photographs; photographers and dates unknown

“When you’re looking at a photograph, how do you know if the people in the image are queer?” JEB says. “With the introduction [for ‘The Dyke Show’ screenings in 2023], I had the chance to introduce a new visual to that discussion, and these are the two photographs I picked. The art world didn’t pay attention to found and vernacular photography like this. Curators and academics are finally beginning to acknowledge that there’s a lot of beauty in these kinds of representations, which were formerly not considered art.”

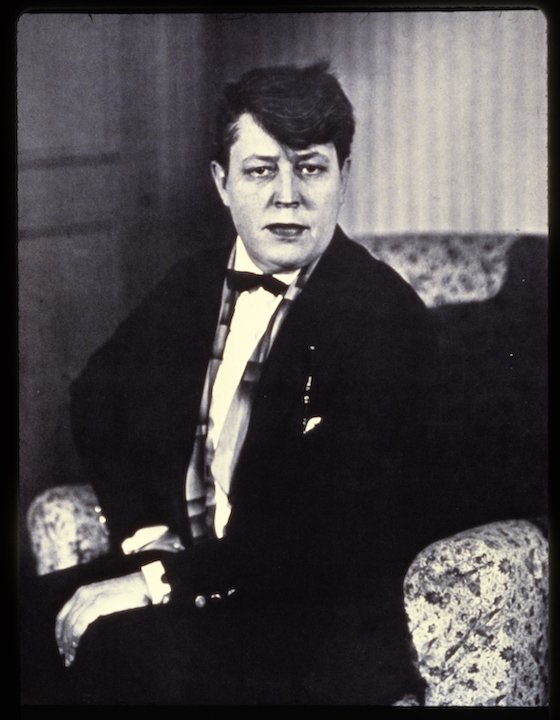

Berenice Abbott, “Jane Heap” (1928)

“This is Abbott’s photograph of Jane Heap, who, with her lover, was one of the editors of The Little Review, a very influential literary magazine,” JEB says. “What’s wonderful about this one is the direct connection between the photographer and Jane; you can feel her intensity. What is beautiful to me about this representation is, between the clothing, the posture, and the expression, that is what I would identify as a butch lesbian. And as a butch lesbian myself, that is a beautiful thing to see.”

Alice Austen, “Julia Martin, Julia Bredt and self dressed up, sitting down” (1891)

“Alice Austen is one of the favorites, then and now, of ‘The Dyke Show,’” JEB says. “I have this photograph on the wall of my home and I look at it every day—I love it. First of all, the cross-dressing speaks to how that has always been a part of queer lives. The group of friends is clearly having fun, and the umbrella shows what a sense of humor they had! People love Alice because there is no doubt she was a lesbian.”

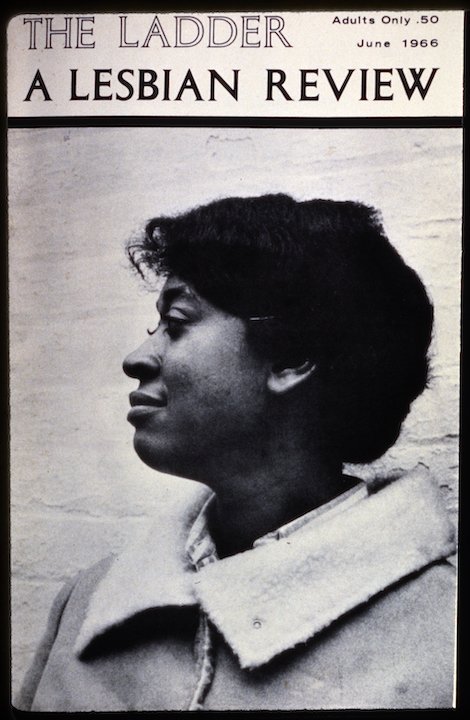

Kay Tobin Lahusen, “Ernestine Eckstein” (1966)

“Kay was the first openly lesbian American photojournalist,” JEB says. “She was responsible for putting photographs of real lesbians on the cover of The Ladder, the first nationally distributed lesbian publication, such as this one of Ernestine Eckstein, in 1966. In her interview in the magazine Eckstein said, ‘Homosexuals are invisible, except for the stereotypes, and I feel homosexuals have to become visible and to assert themselves politically. Any movement needs a certain number of courageous people; there’s no getting around it. They have to come out on behalf of the cause, and accept whatever consequences come.’ So she was clearly aware of what she was doing, and was doing it for political reasons. I thought Kay was an important person to represent, but I also wanted to include a Black lesbian from the 1960s, as an affirmation that queers and lesbians of color existed way back into history.”

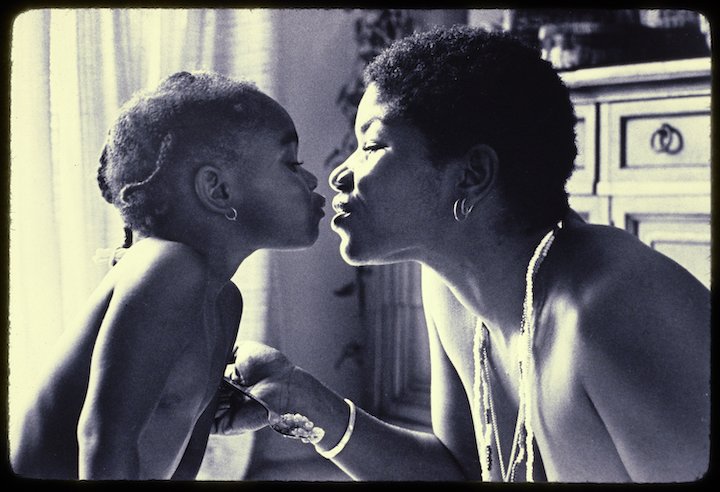

JEB (Joan E. Biren), “Darquita with her mother Denyeta” (1979)

“Several people have said to me, ‘Until I saw this photograph in Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians, I thought that if I was a lesbian, I couldn’t be a mother,’” JEB says. “That’s the power of art. That’s the power of representation. It makes it possible for people to imagine what they have been told is not possible. When you make something visible, it opens up worlds to people.”

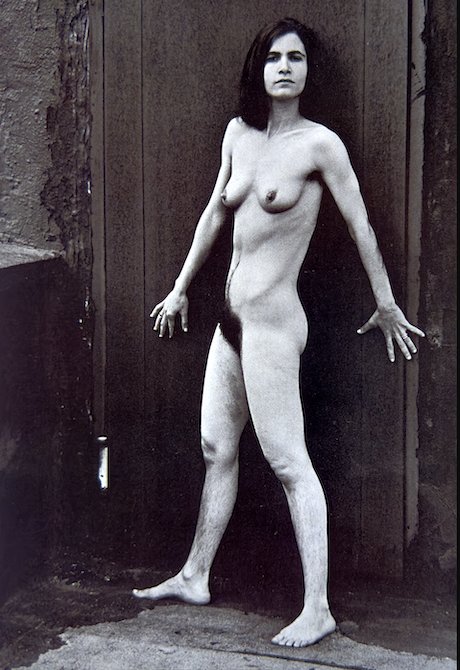

Cynthia MacAdams, “Joann Schmidman” (1976)

“In ‘The Dyke Show,’ I was trying to show how between women, between queer people, how the gaze was different from what we now identify as the cis male gaze,” JEB says. “This image was made in 1976—people weren’t talking about the male gaze the way they do now. I was trying to show how it was possible to photograph a nude woman and not sexually objectify her. Cynthia has successfully done that here: This woman is completely naked and still totally in possession of herself. She’s not presenting herself to you for your pleasure. You see her as a whole person, not as just a body, and that’s what makes her gorgeous to us, right?”

Tee A. Corinne, “Sinister Wisdom Cover/Poster” (1976)

“This photo has been called one of the best-loved images in Dykedom,” JEB says. “In the seventies and eighties, you would go into a lesbian house and this image would be on the wall. It was the most reproduced, most recognizable lesbian image for years. These are real lesbians making love—Tee used a process called solarization that not only protected their privacy but captured the uniqueness of lesbian sex. Tee’s work was a huge influence on me and many other women artists. It was so radical and revolutionary at the time. To be able to make an image of lovemaking that is tender but also sexual is not easy. Tee was an amazing photographer in her understanding of what was erotic. She wanted her photographs to be beautiful in a big and powerful way. She understood that explicit sexual imagery like this made lesbian existence undeniable.”

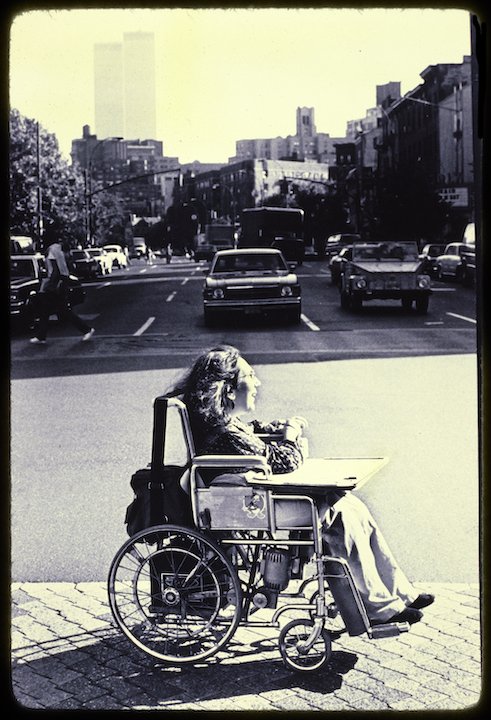

JEB (Joan E. Biren), “Connie Panzarino” (1979)

“This is Connie, whose quote for the book was, ‘There is a disabled closet, as well as a lesbian closet,’” JEB says. “What I love about this picture is you can see she’s under her own steam, her own power. That’s how I experienced Connie: as a mover, joyful—going somewhere.”

Laura Aguilar, “Plush Pony #2” (1992)

“I included this one in the epilogue,” JEB says. “Laura Aguilar, another photographer who was not recognized in her lifetime, described herself as a fat, brown, working-class butch. She photographed within her own communities, which allowed her to build trust with people. In this photograph, again we have a butch lesbian, in the foreground, looking right at you. Let me tell you: There is no way a butch lesbian is going to stand there being herself looking at you in this way if she does not trust you. It’s a combination of what was going on with the Berenice Abbott and the Alice Austen images above. You can see how all the influences make something I consider a queer sensibility. This queer sensibility does not exist without trust between the photographer and the muse. If you share community—be it race, class, gender, sexuality, or multiple identities—that is a foundation for trust which creates a different energy exchange. I believe that the trust, energy, and love show up in the image.”