Abraham Burickson remembers when it all started to click. The sometime poet, sometime writer, and sometime performance artist took a break from architecture school and traveled to Istanbul to study Sufism. There, he visited famous destinations such as the Hagia Sophia and the Blue Mosque—spaces that are known for their intricate tile mosaics and spectacular scale—but also smaller mosques outside the tourism circuit.

What he remembers most is how all the details imparted a sense of transformation, from passing through thresholds to seeing ritual washing areas to being in a prayer room where he was oriented toward Mecca along with dozens of other worshiping people. The architecture helped him feel deep spirituality in an embodied way. “The building was absolutely engaged in some crazy mojo,” he says. “It seemed like a superpower, like magic.” But this wasn’t how he was learning about architecture in school, nor was it like what he saw while working in architecture firms both large and small. So he created his own niche in the profession: a practice that he defines as “experience design.”

Burickson’s philosophy leads him to design experiences, not things. What this means is that the end result of his creative work is at least a budge, and at best a shift, in someone’s worldview. It’s not about bringing another user-friendly object into the world. Burickson has achieved this through The Long Architecture Project, a studio he runs that makes homes that reflect the values of the people who live in them, and through Odyssey Works, an artistic collective he co-founded in 2001 that stages elaborate performances, some lasting several weeks, each for a single person. These events have included creating a temporary utopian community, writing a “lost” book by an early 20th-century Argentine author for a literature buff, and producing a radio talk show for an NPR fan.

These performances offer moments of wonder, fear, tenderness, and empowerment—a full spectrum of emotions that afford someone a deeper understanding of who they are as an individual. “I was driven to look more carefully at my life and live it more carefully, and that’s transcendent in the actual sense of the word,” said the novelist Rick Moody after participating in an odyssey that sent him to a remote field in Canada to hear a cellist perform.

When Burickson began describing his work as “experience design,” in the early aughts, it wasn’t the buzzword that it is now. The concept has since been mainstreamed by UX designers, the entertainment industry, and (especially) marketers. Amid this boom, Burickson has shifted his attention from an audience of one to an audience of thousands by writing Experience Design: A Participatory Manifesto (Yale University Press), a book out this month complete with illustrations by Erica Holeman and a foreword by Ellen Lupton.

It lays out how this approach to making is relevant for anyone, not just designers. Like George Nelson’s How to See, Burickson’s Experience Design is about adopting a new perspective. He invites readers to host dinners for their friends, muse on artworks such as Walter De Maria’s “The Lightning Field,” and even rip out the book’s pages in order to get to a place of “more sensory engagement, more liveness, and more connection,” as he writes. I recently spoke with Burickson to learn more.

In simplest terms, how do you define experience design?

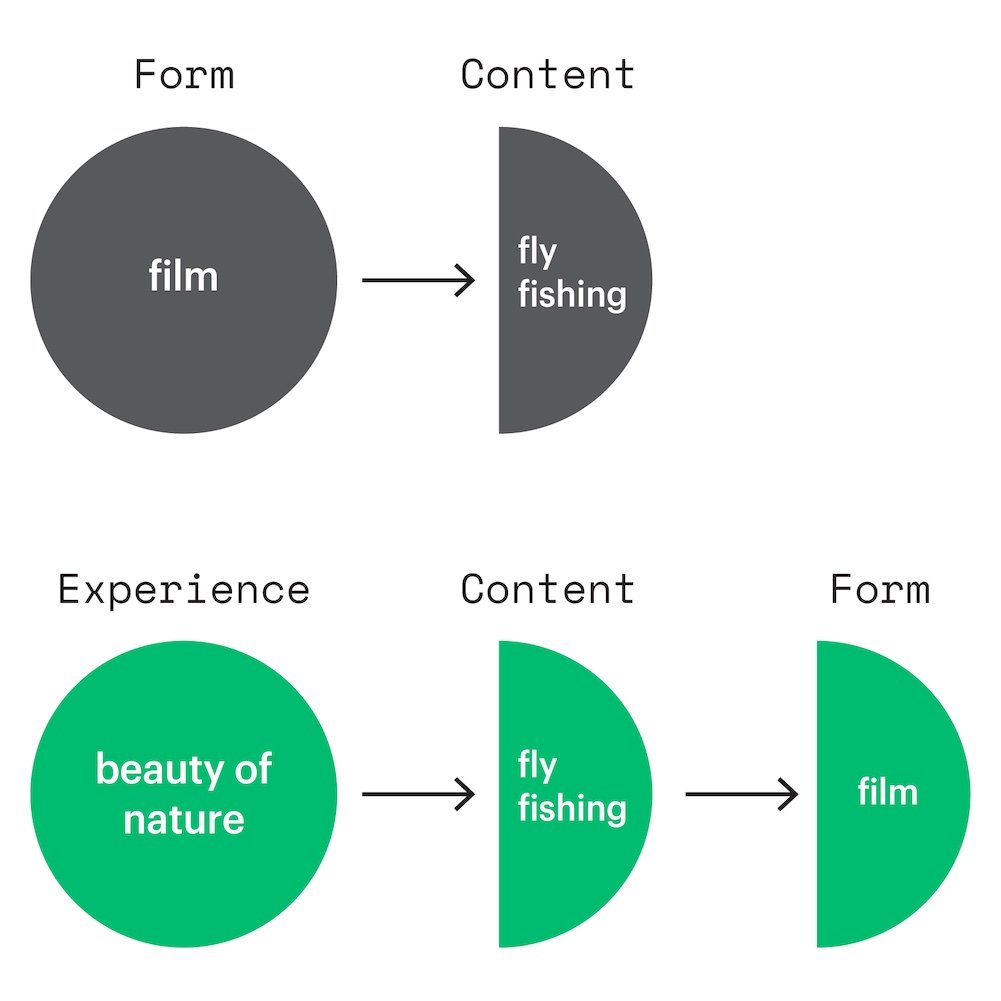

Experience design is the practice of making the human experience the product of the design practice. An experience designer first identifies the experiential aim then decides what approach will be necessary in order to achieve that aim. This can be applied to any creative process, from theater to architecture, from HR to political activism, from journalism to science. Experience design is not about categories of practice; it’s about relationality and how something is received in the end. We can use any tools we want—including designed objects—to achieve that.

You view experience design as not merely solving problems or making life easier; rather, it’s about making someone feel something and changing their lives through interactions. It’s not about the thing, but how the thing impacts a person. Tell us more about this perspective and what brought you to it.

So much of what I call “thing-based” design is creating the “thing” and putting it out in the world—sort of like how the Voyager probe is searching for alien life to listen to the Golden Record. We design a spec house or chair, but do we ever meet the person who’s going to live there or sit in it? There’s something very “gods up on Mount Olympus” about most design processes, which is, We’re casting down the solution to you from a hole in the sky. It’s a modernist vision.

This kind of industrialized design process is not old. Before, design happened through a community of engaged people. How else could a cathedral get built over a course of one hundred and fifty years? Design was always relational. On a personal level, I think that being in relationship with other people is what makes life great and if I’m making things, I want to be in relationship [with one another].

For much of my life there was no role of “experience designer” to lean in to, so I always felt at odds with the design practices I was involved in. I often felt like an outsider. The way I was trained in architecture, [was to] largely sit in front of a screen and move a mouse around to make a projective visualization. It’s sort of like the architect in The Matrix Reloaded: thinking through something but not actually living it. We begin in this intellectual space.

But everywhere I went, I was encountering this question: How is design affecting me and those around me? I remember going to a Tennessee Williams play and walking out with my eyes crossed and seeing the world differently. Or watching Playtime by Jacques Tati and understanding the world as a space of absurdity. I’m not that interested in the film Playtime; I’m interested in the fact that this French filmmaker was able to change the way I engage with my world.

Through Odyssey Works, you design these elaborate, highly personalized experiences for people that sometimes last for months. This work is similar to what you do in The Long Architecture Project, where you design homes for clients that facilitate experiences they want in their lives. How do you figure out what to create for people, and what they really want and need?

We spend time with the client. Sometimes we go on walks with them. Once we started the interviews at the Russian and Turkish Baths, in New York.

So you’re getting to know people in an intimate and vulnerable way.

Absolutely. And I’ll also add that I was in the sauna, too.

After learning all this information about somebody, we ask ourselves and our collaborators, What do you wish for this person? It’s a question that is structured by what’s at the essence of relationality, and perhaps, of loving somebody. It’s a wish for them on a life level. And we as artists have a wish to create a new experience. We’re not asking ourselves, What do you think this person needs? Or, What do you think this person wants? It’s not that interesting to simply realize someone else’s wish. Like, if someone says, “I want to jump out of an airplane and learn how to fly,”—that’s great; go do it. People should realize their own wishes.

One of our clients was a teacher and the odyssey we designed for her was a pilgrimage. We wanted her to engage with this from a place of empowerment, so an experience we designed for her was leading a workshop. We wanted to create a scene for her of going into her strong place, of embodying her intelligence. The next part was this wild self-interrogation and then a long journey quite far.

It would be very different to engage with that from a place of surprise. Surprise makes us open, delighted, and receptive, but we don’t become empowered. Delight isn’t good preparation for an analytical understanding of your life. So much of experience design is preparing conditions so that a person can move onto the next stage of what you’re creating in an appropriate way.

When you started discussing design as an experience, you were defining what that meant. Now, as your book is published, it’s widely discussed. How do you feel about the mainstreaming of this concept?

I feel extremely hopeful that experience design is entering into the vernacular, but it is an emergent moment. There isn’t an orthodoxy right now, and that’s really exciting. That means that we’re in a time where we can debate and develop and advocate for the proper application of what I believe is an incredibly powerful, culture-changing approach to making.

At its core, experience design invites us into an ethical starting place for design—because what is ethics if not the effect we have on other people? We have an opportunity to rethink the ways we approach all of the huge, seemingly intractable problems we face. Experience design isn’t really about designing interfaces or immersive spaces. It belongs in so many places and in asking how we address problems of loneliness or our relationship to the environment.

I’d like to explore the ethical side a little more because we see experience design play out in a lot of unethical ways, like making it difficult to cancel a subscription or terms and conditions that are too long for anyone to read, among other so-called “dark patterns” that incentivize specific actions. What are your thoughts on this?

Any tool can be used for good or evil, and I think it’s really instructive to look at the ways experience design has been used brilliantly for evil. For example, Vladimir Putin basically has been rethinking what Russia is in order to defend his actions in Ukraine. It’s an enormously extensive world-building effort: he’s rewriting history, he’s restructuring education in schools, he’s changing language. These are all experience design projects at a very large scale. We’ve seen similar things happen throughout history because these efforts can be effective and powerful. At the same time, in Ukraine, you see another kind of world building going on. This is all experience design.

An ethical activity means it’s about the effect we have on others, and your ethics could be on the good side or the bad side. Just because you understand you are having an effect doesn’t mean you’re doing the right thing with the effect. If we put out these tools and say, “Do what you want,” things can be rendered to the lowest common denominator. These tools can be used to get more eyes on a social media account as your anxiety jacks up and your loneliness increases.

But what if we say that the most important questions to ask are: What is the real effect you wish to have on the world? What is your ethical purpose as a designer? And then, How does that render down from career, to job, to project, to design moment?

Much of so-called “good design” has been created from an experience of “user friendliness,” which often translates to removing pain points. But what is there to gain from pain?

Pain is movement away from comfort, and we can put things on a comfort-pain spectrum. To bring it back to the notion that every design move has a set of affordances, we can re-ask the question: What is our reason for designing for ease and comfort? What is our reason for moving away from that?

I recently had a conversation with a group of experience designers about how nothing can change without breaking habits. That seems pretty obvious. But when you think about design, it’s mostly about building comfort around the habitual and making things more efficient. Pain points are the problem, right? We never ask if it’s actually a good thing to be making everything about comfort. But if you add pain points, there is a break with the ordinary. If we want to change things, we need these pain points. And if we’re smart about them, pain points aren’t just things to cause reactions; we’ve designed a way to prepare our audience or user to be affected by those pain points in a positive and attentive way.

This makes me think of the chapter in my book about empathy. As a practitioner, empathy may be what you gain the most from pain. Empathy forces us to project ourselves into the understanding of another person who may have pain. The only way to really have empathy for that person is to really go into that pain—and you might not be ready for it. Empathy, when rigorously engaged with, forces us to recognize our own limits. I can have empathy for you, but I don’t know that much about you. The risk is for me to make a whole bunch of assumptions about you and call that empathy.

Then we get into this problematic, arrogant mode of empathy that makes us feel great about ourselves and makes us disregard the realities of others. There’s a kind of painful humility that needs to be applied in order to say, “I need to step back, do some research, ask some questions,” and also ask, “Am I the right person to do this?”

These are painful moments for a designer. But this is the real work of real empathy. And without the real work of empathy, how can you presume to have any role in designing an experience for another person in an effective or ethically rigorous way?