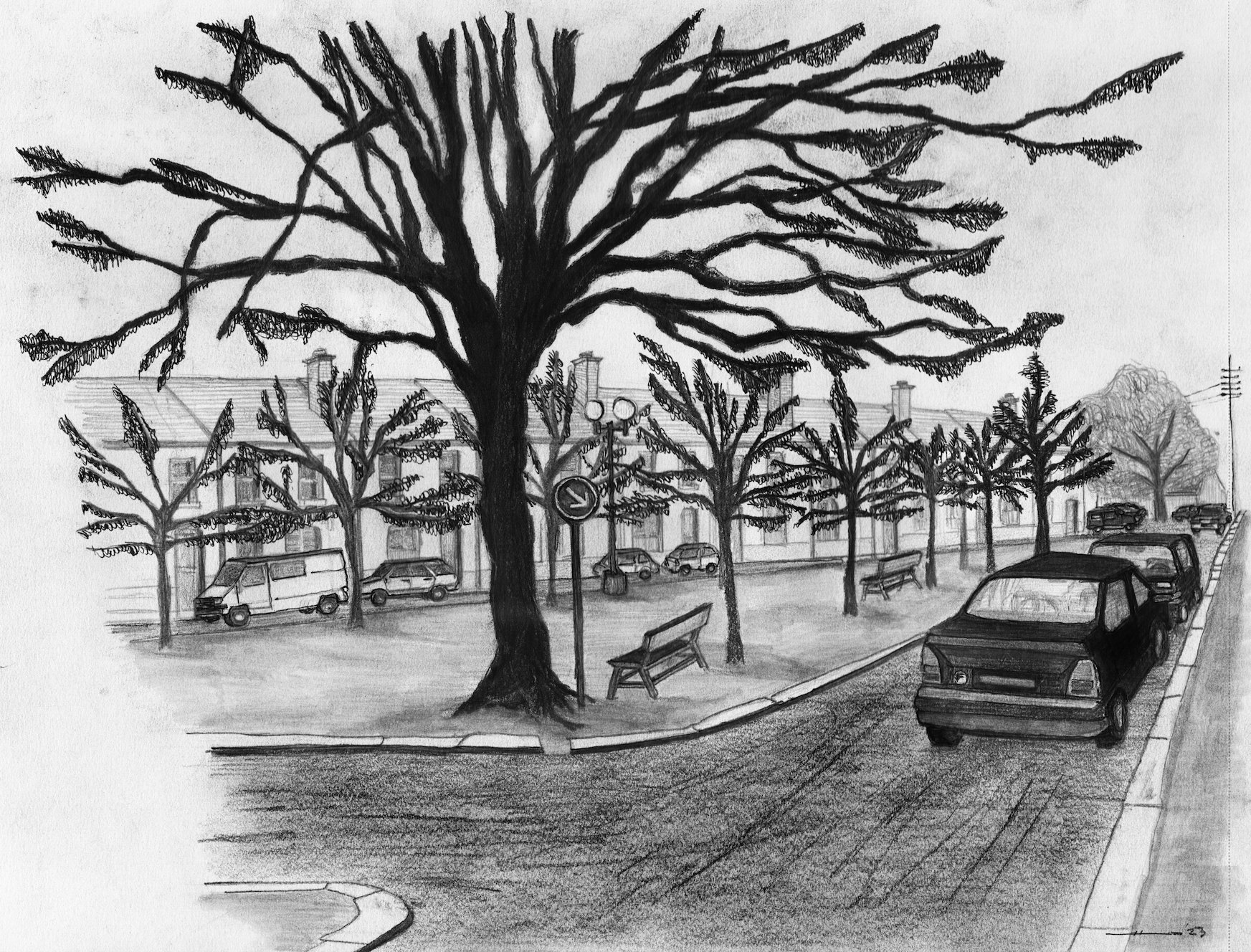

Place Léon Aucoc is the kind of small square that characterizes classic French neighborhoods, exactly the kind of thing one might think of when envisioning everyday life (albeit idealized) in a quartier. It is in a big city, Bordeaux, but it feels like it could be in an old village. It is near the huge rail yards and the dense tangle of tracks behind the Saint-Jean train station, but these feel somehow distant. It is not beautiful and it has no real landmarks, yet it has a coherence. It features a few sparse benches, an edge defined by some modest lime trees, and a place where a handful of locals, mostly older men, play pétanque and while away the seemingly pleasant afternoons of the long French retirement under the shade of trees and against the gentle rustling of leaves.

In 1996, as the city was going through a flurry of speculative proposals to redefine itself as a modern metropolis through the medium of architecture, Paris-based Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal (who had both studied in Bordeaux) were commissioned to redesign the little square or, in the terms of the English translation of the transaction of the brief, “to embellish it.” They spent some time studying Place Léon Aucoc, talking to local inhabitants and observing how it was used throughout the day and over time.

Their response to the brief has become a kind of urban legend among architects. It is fine, they suggested, just as it is. Their proposal was, effectively, to do nothing. Well, it was a bit more refined than that: The architects recommended that the trees be better cared for, the gravel be replaced, and the square be cleaned more regularly and better maintained.

You might argue, counterintuitively perhaps, that this, from an architectural firm, is the most radical response imaginable. It is an extreme irony that what might appear as extreme conservatism—a laissez-faire notion of a situation not needing improvement—is also an extreme and almost revolutionary proposal. That irony stems from a late-capitalist worldview based entirely on growth and myopic about any other possibilities. Change, churn, and productivity have been at the heart of capitalism’s drive for most of its existence, and have been supplemented in recent years by the Silicon Valley mantra of disruption, of moving fast and breaking things. Moving slowly, or not really at all, and leaving things unbroken is rarely considered or admired.

The idea of doing nothing is seen as synonymous with decline. Something always has to be done. Lacaton & Vassal’s response to that brief, then, marks a hugely significant point of departure for architecture, a new understanding that sometimes the answer really is “no.”

This might have been a story lost in the obscure annals of architectural culture were it not for Lacaton & Vassal’s subsequent incredible success. Awarded the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s most prestigious award, in 2021, they are among the world’s most influential and admired architects, yet they have remained doggedly—and admirably—committed to their work in social housing and to a philosophy they have simply defined as “never demolish.” They work with existing structures, often leaving residents in place during construction so as not to damage the intricate and delicate webs of community and relations while ensuring, of course, that the embodied carbon is not wasted and that insulation and environmental performance increases in the process.

Lacaton & Vassal came to prominence in 2002 with their transformation of the Palais de Tokyo, a bold design that stripped back the interiors of the grand art deco building to its raw bones, exposing concrete, rebar, rusting steel beams, and cavernous Piranesian basements that were never meant to be seen, creating from the unadorned structure an almost industrial sense of space in one of Paris’s grandest 20th-century set pieces. This subtractive, rather than additive, design became the Parisian riposte to London’s Tate Modern, completed a couple of years earlier by Herzog & de Meuron. (Lacaton & Vassal also oversaw the museum’s renovation work and refurbishment, in 2012.)

But it was the pair’s transformation of social housing in Paris and Bordeaux that cemented their reputations. Rather than demolishing the 1960s concrete slabs and decanting their residents, as was being done all over France at the time, Lacaton & Vassal essentially wrapped the blocks in cheap polycarbonate, creating a new layer of space—terraces, conservatories, and rooms that were as much outside as they were in—hugely expanding the footprints of the apartments while keeping the residents in their homes. Their sense of place was left intact while their actual physical accommodations were transformed, expanded, and given extra insulation in a modernist mold. The effort is now among the most cited and studied projects in social housing and one that began to point the way not only to adaptive reuse, but to a more delicate sense of care for existing homes, in both their physical and psychic dimensions.

In France in particular there has long been a movement toward a new sense of care for the already-existing. Perhaps in reaction to a tradition of Haussmannian destruction and grand visions that led to the wholesale demolition and rebuilding of central Paris, Corbusier’s (unrealized but hugely influential) grand plans, and the vast public housing developments that define the Banlieues beyond the Périphérique, an alternative tradition has emerged. It is rooted in part in a Situationist notion of subverting the existing conditions through aimless drifting (the famous dérive) and using the city without consuming, subverting its capitalist intent. It is an approach that pays attention to the quotidian—what novelist Georges Perec referred to as “l’infra-ordinaire,” as in the opposite of the extraordinary—and attempts to derive pleasure from everyday ritual and repetition, from the processes of the everyday life of the city itself. That appreciation, the legacy of Guy Debord, Henri Lefebvre, and Raoul Vaneigem, created a body of work dedicated to dissent from the commodification of public space and architecture (a deep concern with Marx’s ideas on commodity fetishism) and a wariness of the notion of the spectacle on which Debord wrote so dazzlingly.

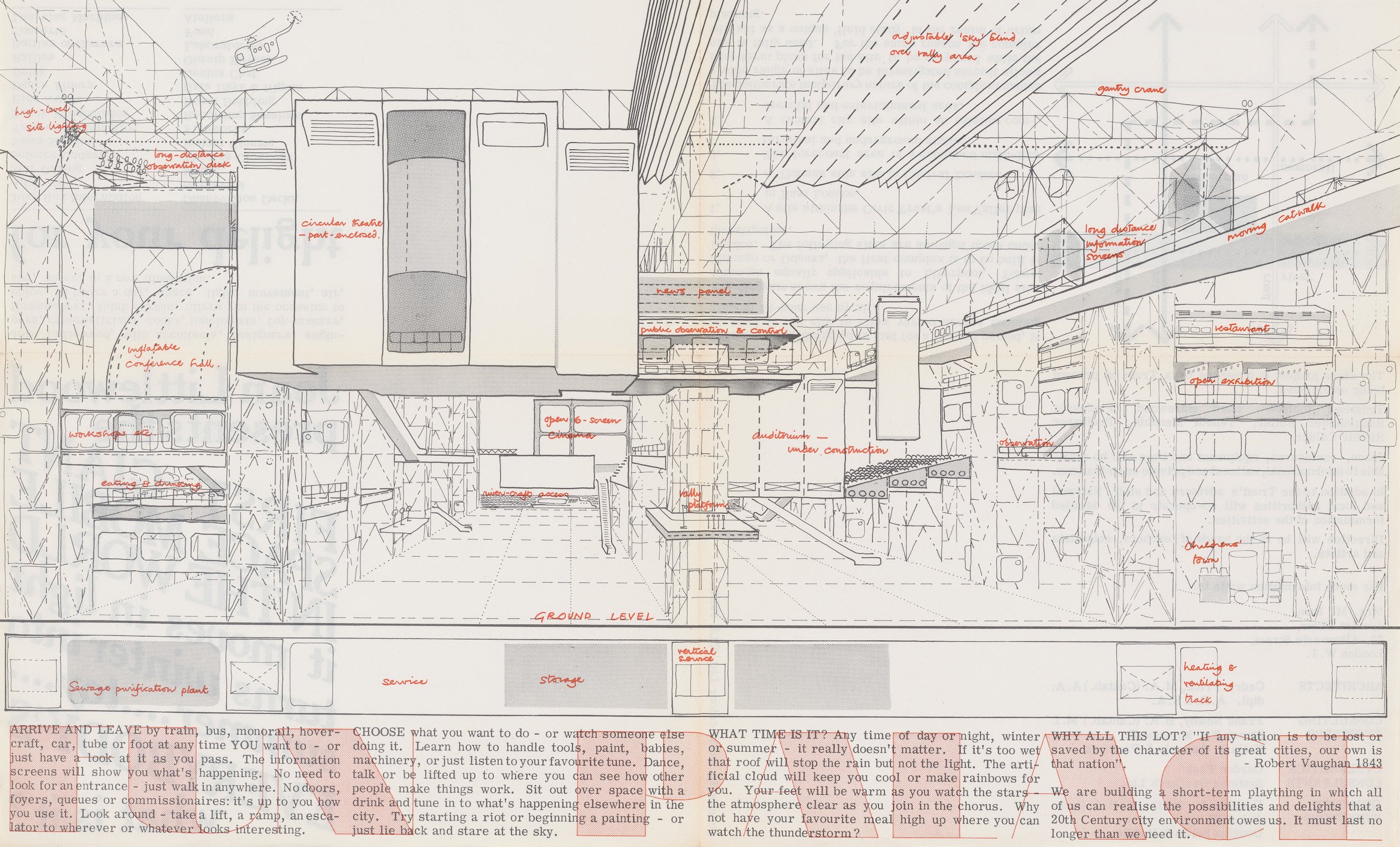

But there was also a vein of resistance over the channel in Britain, with it every different culture of ad hoc-ism rather than grand plans. And no one characterized it better than Cedric Price, whose oft-quoted suggestion that the best solution to an architectural problem may not necessarily be a building haunts the practice, even two decades after his death. Price was a remarkable figure whose built output was almost negligible yet whose influence has loomed over contemporary architecture since the 1960s. His design for the Fun Palace (1959–61), a structure capable of accommodating varying cultural needs over time, an infrastructure rather than an architecture of culture, was a huge influence on the Centre Pompidou by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano. But while the latter has ossified into heritage, the former remains an idea, undiluted and innocent.

For Price, the building was secondary—the ideas were the thing. Late in his career, he proposed a wetland habitat in Hamburg for migrating birds. Now, that sounds visionary; back then it was dismissed as nuts. He was once famously commissioned to design a house for a sparring couple. He suggested that what they needed was not a house, but a divorce. Architecture, he said, is rarely the answer.

That both Price and Lacaton & Vassal become so widely admired (though not, unfortunately, much emulated) is a sign that architects are shifting their gaze, or at least that they are feeling guilt at their profligacy with resources and energy, their complicity in climate catastrophe. Architecture today is riven with a sense of insecurity. Architects have become painfully aware of the indefensibility of a position that is liberal enough to acknowledge the crisis yet utterly contingent on a panoply of toxic and polluting materials as well as a global supply chain over which they have little control. The increasing propensity of biennales, exhibitions, publications, and academic courses to concentrate on the resource-poor Global South and on social and political activism, addressing racism and decolonization is, in part, a reaction to this complicity and the efforts being made by academia and the media to distance themselves from the traditions of the profession.

It is easier to focus on the world’s obvious injustices than it is to address them through building with its inevitable contingencies, capital, compromises, and carbon-intensive processes. When this last happened, in the 1980s, it led to a moment of paper architecture, visionary designs which were meant to provoke rather than be realized. Now it does not even dream in visionary terms, but rather dwells on the intractable realities on the ground and on an array of small-scale, craft-based interventions.

Arguably the acknowledgement that most problems cannot be solved by more architecture is in tune with Lacaton & Vassal’s position at the Place Léon Aucoc. Elsewhere in France, Patrick Bouchain—best known for his cultural architecture often made from waste materials, cheap timber, reusable elements, scaffolding, and a kind of stage-set material improvisation—has been quietly reimagining a once-condemned street in Boulogne-sur-Mer into colorful, smart social housing complete with infrastructure but with very little architectural change. Bouchain’s work has been facilitated in the past by his closeness to influential political figures and a reverence in government for culture that is wholly alien to Anglo-Saxon politics. It has allowed him to cross effectively from the stage to the street.

The British collective Assemble are nevertheless attempting something similar in Liverpool with their Granby Four Streets project, an attempt to resuscitate the last four streets in a once-thriving neighborhood by reviving the existing houses in a community-led project that involves reintroducing public amenities, workshops, and creating a remarkable (and theatrical) winter garden in the brick shells of a pair of derelict houses. One of their first projects, the Cineroleum, has stuck in my mind as a brilliant intervention on the site of a former London gas station. They added a set of curtains made of silvery Tyvek insulation, and ruched them and arranged them as walls that would descend to envelop the space. Dramatic and striking, it was a quite brilliant piece of urban theater.

Beyond these are countless examples of cooperatives, squats, occupations, community projects, and innovative and socially conscious spatial practices that fall outside the margins of more conventional architectural practice. The responses to the pandemic saw the widespread adoption of “urban acupuncture,” usually reversible measures by the wealthy cities of the global north that included traffic-calming strategies and bench/planters that were often, in the manner of capitalism, immediately co-opted and commodified by commerce in the drive to effectively privatize public space using outdoor restaurant seating and sheds. Sustainability itself has been co-opted by a new “green industry” that is commodifying the climate crisis so that even the responses to catastrophic conditions become about “green growth,” often losing sight of the primary problem, which is the implicitly capitalist idea of perpetual growth itself.

Architecture is, arguably, being understood by a younger generation less as a profession and more as an expanded field of practices that exploit architectural understandings of the complex web of relationships between the economic, environmental, spatial, social, and intellectual underpinnings of the built environment and the territory. It also, perhaps, constitutes a reaction to the star system in architecture in which a few global practices dominate the discourse, becoming role models for younger architects and workhouses for ambitious new graduates, their labor exploited in an extractive manner that echoes the excesses of the construction industry and the making of blockbuster architecture.

The unspoken problem is that young, passionate architects, in choosing increasingly to vacate the world of big construction in protest against these extractive practices, labor abuse, neoliberalism, and environmental damage, are leaving the floor open to yet more mercenary and ruthless actors who do not even have those modicums of guilt and self-doubt that characterize the architectural profession. In refusing to participate, they might themselves be doing less damage—but are they also abdicating responsibility? Architects need to be able to accept the commission and question the brief, asking, “Is this really necessary? Might we do less? Or nothing? And how?” It is a question hugely at odds with a system that values output and a commercial expectation based on extensive previous experience and turnover. But it is humility that will begin to compensate for the enormous damage that has been done, and is still being done, to the planet by construction.

Or we could say it is, in fact, hubris rather than humility. Like Bartleby the Scrivener, architects have to be able to take the job and only then suggest they’d prefer not to. Architecture perhaps needs a code akin to the Hippocratic of the medical profession: Their first responsibility should be to do no harm.