For most visitors, a trip to Hiroshima centers on the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, anchored by the ruins of the Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall at one end, and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum at the other. Designed by a team led by Kenzō Tange beginning in the early 1950s, the park is now home to numerous monuments that honor the roughly 140,000 people who died after the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the city nearly eight decades ago. Transfixed visitors to the museum move silently among displays of charred and disfigured fragments of everyday objects and building materials left in the bombing’s wake. They behold the concrete, brick, and steel shell of the hall, built from 1914 to 1915, which was rechristened as the Genbaku Dome, or Atomic Bomb Dome, after the war.

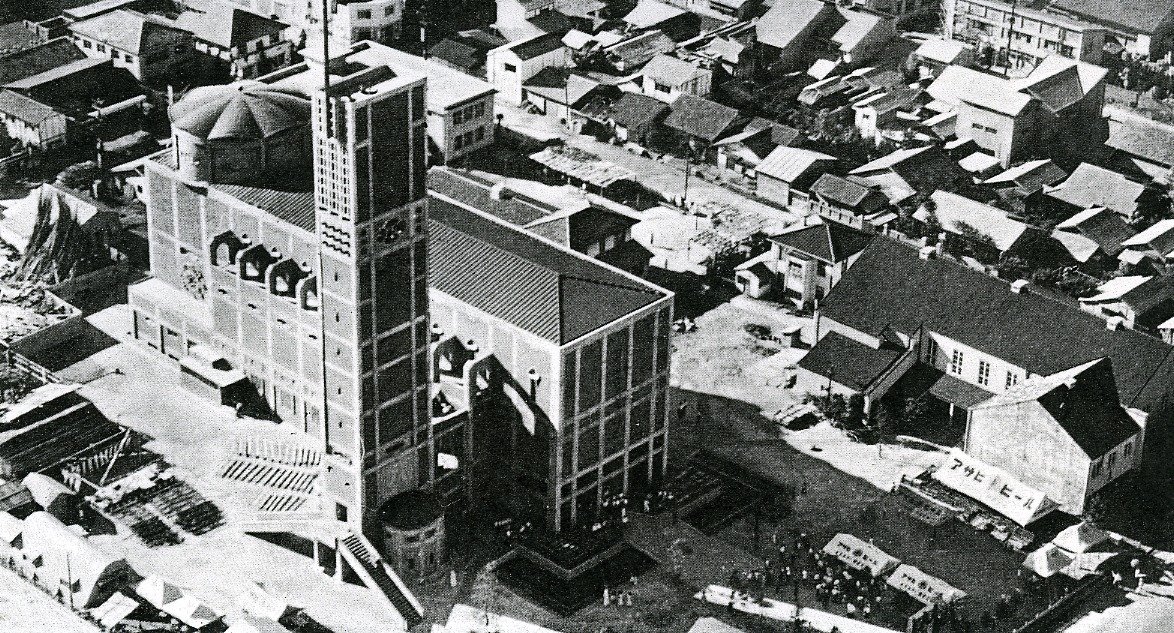

But there is another, much less-visited site, about a mile east of the park, also dedicated to ending war and built to commemorate the dead: the Memorial Cathedral for World Peace, completed in 1954 by Togo Murano, one of Japan’s most inventive 20th-century architects.

Most immediately striking about the basilica-plan church and its tall belltower is the expressed concrete frame and brick infill on the exterior. In the insistent rectilinearity of the façade, observers have recognized Murano’s absorption of the principles of both traditional Japanese wood-construction techniques and the articulated rationalism of French architect Auguste Perret, one of the first in his field to use reinforced concrete frames expressively. Indeed, during Murano’s formative years and early career, many Japanese architects sought to integrate aspects of Japanese and Western modes of building. But in Hiroshima, this façade means much more.

I visited the cathedral one afternoon this past spring. I had come to study Tange’s work as part of my research on modern architects’ responses to ruins. I quickly discovered that being in the city as a scholar and a U.S. citizen requires a kind of psychological balancing act, as I simultaneously processed architectural evidence in the dispassionate mode of a historian and grappled with feelings of abject sadness and an amorphous sense of culpability connected to the passport I carried.

In Hiroshima, where the world is implored to make peace and where history is measured relative to 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, the past and present, the done and the undone, collapse into one another. In this place, everyone is a time traveler. The what-ifs and if-onlys swirl in the mind, intermingling with intimations of the impending and unfolding preventable tragedies of today, from climate change to war. Facing the historic pain of Hiroshima sharpens the pain of the present by disinterring a latent fear that we will fail to muster the will or marshal the resources to forestall mass suffering in the future.

When Murano designed the cathedral, much of the city lay in ruin, its wood buildings devoured by fires ignited after the detonation. But even close to the bomb’s hypocenter, some structures partially withstood the blast and conflagrations. These were almost uniformly concrete-frame buildings.

In retaining the shell of the Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall as the foremost landmark of Hiroshima, the city symbolically transfigured the ruin into a kind of material stand-in for the bomb. By the beginning of the 1950s, atomic tourism had begun. Then, as now, visitors came to mourn and to comprehend. But, consciously or not, many also came longing for sensuous contact with the bomb, which the ruin, along with objects in the museum, provides.

Murano seems to have understood this desire. Yet rather than risk trafficking in a potentially grotesque, fetishistic commemoration, he created an architectonic memorial whose power lies in its materiality, dualism, and associative meanings.

In the Hiroshima of the late 1940s, when Murano began designing the building, brick-filled, concrete frames were the city’s foremost, concurrent symbols of survival and destruction. Murano’s building poignantly summons the ruins, yet also seems somewhat unfinished. On each panel, a few bricks are advanced, as if they have slipped out of place, as some did on the remaining partial walls of the Atomic Dome. Cathedral masons intentionally left the mortar messy in many places, and it appears to drip over the rough gray bricks, which were formed using the ashes of incinerated objects. With the material remains of things the bomb destroyed physically embedded in the walls of the building, the cathedral is fragment and phoenix at once.

Murano’s walls invite us literally to touch and metaphorically to hold absence and presence—death and resurrection—together in our minds, as we perceive them tactilely and visually. To probe the joints (to lay a finger on the side of the building) and behold the ash-infused brick is to come closer to death in Hiroshima, but also to confront pain-laced doubt about whether we can turn back the forces of destruction in our time.

The cathedral challenges us to consider the ethics and dynamics of sensory satisfaction, material allusions to devastation, and architecture’s potential to awaken politically charged empathy. In balancing material roughness with tectonic refinement, and with the associative play of past and yet-to-come implied by the ruined/unfinished dichotomy, the building materializes Hiroshima’s symbolic status as the preeminent inflection point in human history. It is architecture as linking device and cathartic catalyst.

Unlike many modernists, Murano resisted the lure of wholeness, with its implication of totality. His dueling expressions of meticulous craftsmanship and roughness remind us that there are some things that can never be smoothed out. The building’s anti-wholeness manifests further in the disjunction between the façade and interior, with its evocation of Romanesque churches, and in the disquieting mosaic of the Second Coming above the altar. Installed in 1962, this ambivalent Christ presides over the nave, a huge gold beam slicing unsettlingly through the body, as if to blur conventional depictions of divine light with the memory of the blinding flash that accompanied the blast. It is heaven and hell at once.

Amid the human and ecological violence of our time, can material evocations of pain past and present help us create an architecture that promotes healing and fortifies us for action? Murano’s building provokes us to look on the landscapes of the present as ruins and orient our work toward rebuilding, reusing, and resignifying—not for the purpose of forging new utopias, but as an act of contrition rooted in an ethic of reparation and committed to an aesthetic of hope.