Echo Park, Los Angeles, where the artist and designer Peter Shire was born, in 1947, is a quiet enclave which, around the time of his childhood, was colloquially known as “Red Hill” for its reputation as a haven for left-wingers. (Shire’s parents were both card-carrying Communists.)

In 1972, when he was 25 years old, Shire founded Echo Park Pottery, which he has described as “a simulacrum of an art pottery.” At the time, artists like Peter Voulkos and John Mason were advancing the idea of clay as a heroic, large-scale sculptural medium; in contrast, Shire made cups and teapots, which he glazed in jazzy color combinations and sold at affordable prices. They quickly became cult items.

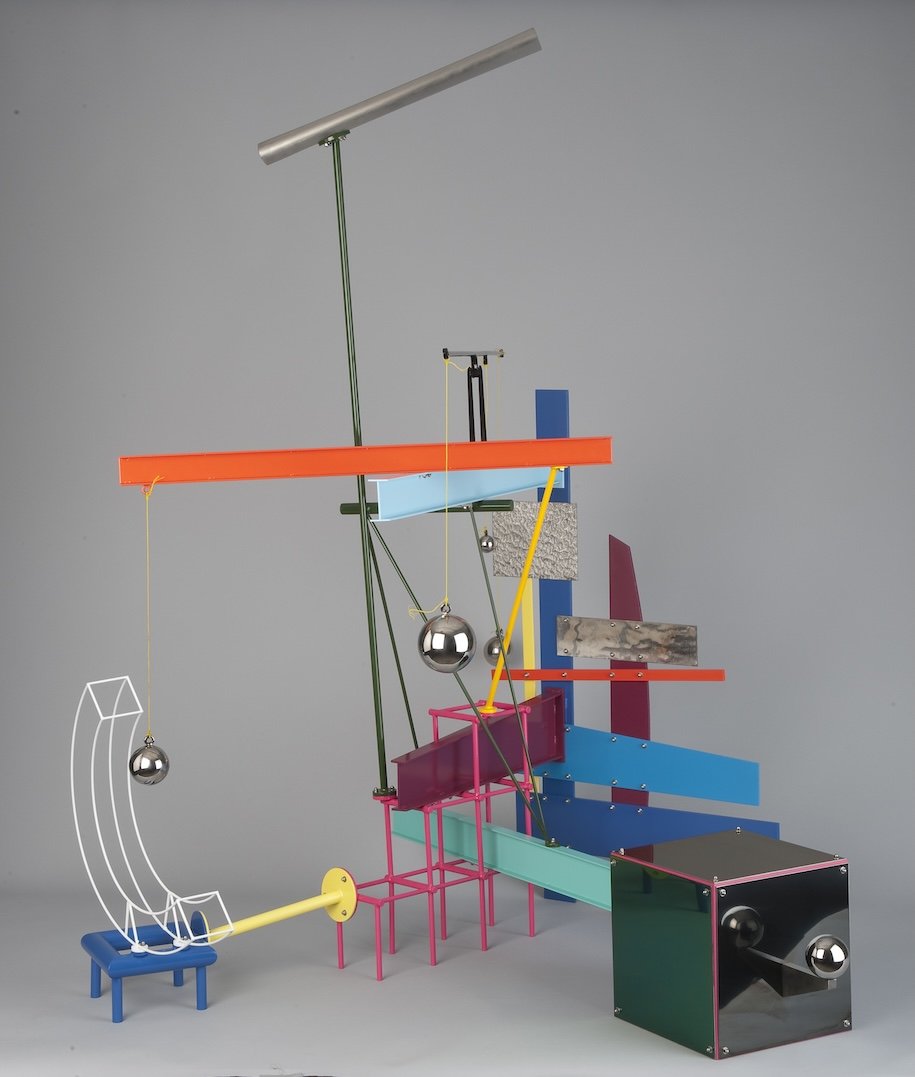

The Italian designer Ettore Sottsass saw Shire’s work in the uber-hip Los Angeles magazine WET (the journal of “gourmet bathing,” as it described itself). When, in 1981, Sottsass established the design group Memphis Milano, he invited Shire to join. He was the group’s only American member. For Memphis, Shire designed outlandish pieces of furniture: the triangular Brazil table, covered in green, yellow, pink, and black lacquered wood, and the asymmetrical Bel Air armchair, whose shark-fin and beach-ball shapes made it an icon of ’80s design, instantly recognizable even today.

Memphis dissolved after just a few years, but Shire continues to make furniture, household items, sculpture, and ceramics in his Echo Park studio. In recent years, the ceramics of Echo Park Pottery (or ExP, as it’s often called, in reference to the tag of the local street gang) have experienced a resurgence of popularity, in part due to the L.A. gallerist Ryan Conder, a tastemaker who sold Shire’s cups at his design store cum gallery, South Willard.

It was Conder who introduced Shire to the young artist Ryan Preciado, sometime around 2015. Preciado was born in 1989 and raised in Nipomo, on California’s Central Coast. He had trained as a carpenter in San Luis Obispo, and was looking for work in Los Angeles. For three or four years, Shire employed him as an assistant in his studio. (He has a regular staff of around four, most of whom work on Echo Park Pottery.)

Meanwhile Preciado was developing his own artistic practice, which builds on his training in furniture production but also draws on various diverse cultural influences, from Chicanx custom automotive finishes to Native American symbols and artifacts to Italian postmodernism. Preciado credits Shire as a formative influence, but he has used his own identity and heritage (Mexican American and Chumash) to establish a viewpoint that is distinctly his own.

In 2023, several pieces by Preciado were included in the Hammer Museum’s “Made in L.A.” biennial. Currently on view at the Palm Springs Art Museum is “So Near, So Far” (through April 13), an exhibition that brings together Preciado’s work with that of Manuel Sandoval, a Nicaraguan American carpenter who worked with Frank Lloyd Wright, Rudolph M. Schindler, and Alvin Lustig, but whose contributions were little recognized until Preciado recently began working to raise his profile in the historical record.

I recently met with Shire and Preciado at Shire’s studio to talk, over cappuccinos and popsicles, about their work and its relationship to history, and how they think about permanence at the different stages in their lives and careers.

Ryan, what did working with Peter teach you? What did you see in his practice that you thought could be applicable to your own?

RYAN PRECIADO: I’d never seen how to run a studio before. A lot of it is just how to problem-solve, while still trying to maintain whatever vision you have, and stay honest to yourself. There was comfort in seeing that you could do that and still not give a fuck. Peter really just makes whatever he wants to make.

How do you think about the long-term endurance of the things you make? I would imagine that part of the appeal of being an artist is that you’re making stuff that will outlast you on this planet. You’re leaving a material footprint.

RP: I think your work can outlast you in the sense of its ideas. I don’t know if anything I make will outlast me. I guess it could. If I thought that far ahead, I’d go a little nuts.

PETER SHIRE: Why?

RP: Instead of just getting something finished, I would constantly be thinking, How can I make it better, and last longer?—and maybe it’d change into something different. So right now, for better, for worse, I’m not thinking about that.

But you’re also now working in a system where things you make, because they are unique and cost a bunch of money, will be looked after by the people who own them. Maybe—even better—they’ll get looked after by museums. There are not many places in the world that are as protected as art museums, materially speaking.

RP: I just did my first restoration on one of my older works. The damage to that piece took place in a museum! I feel like, in most cases, it’s art handlers rather than the owners that cause the damage. It got fixed and now it’s as good as new. I suppose it’s inevitable. If it gets used, it gets used. But even if it doesn’t…. I mean, paintings sometimes need to get repaired too.

Another way of looking at this is that there’s safety in numbers. Your ExP cups, Peter, go all over the world, and they’re very recognizable. But they’re also not so expensive that you can’t use them. So people like me own them. I use mine every morning.

PS: As far as I can tell, in the last ten years, ExP has probably done sixty thousand cups. Six thousand handmade cups a year. They’re in people’s homes. It warms my heart.

As makers, we’re in two or three worlds. We’re in the craft world. We’re in the design world. We’re in the art world. Interestingly, we’re in a world where we may not be of the same economic bracket as the people that we’re directing our work toward. Sometimes I get in trouble for stating that in very bald terms. People get upset.

So what appeals to you about making something affordable that can be used, rather than something so precious that it’s untouched by human hands?

PS: For me, what we’re talking about is the human activity of making things, which is less and less common. If you need a cup, you can go to IKEA. You can go to [the supermarket chain] Vons, and get a [mass-produced] Chinese cup for a few bucks. But how do you want to live? When I was in high school, we had shop classes.

RP: I had the last shop class available in my continuation high school, and then they dropped it after that year.

PS: Half of the machines I’ve got in my studio were dumped out of L.A. City College.

So you’re saying that all of this, your practice, is just a way for you to have an outlet for making things with your hands?

PS: It’s part of the human condition to want to make things, to be productive, to be part of the community, to interact with your fellows and provide for them and for them to provide for you. To be a person of value.

Both your work seems to me to be not only about the impulse to make, but the impulse to live in a certain way. The difference between buying a mug from IKEA and buying an ExP mug, or a teapot even, is the idea that the ordinary things we use every day can have the potential for beauty and grace.

PS: People love IKEA because it’s almost design. It’s a baby step on from somewhere like the ninety-nine-cent store or Costco. I both adore and dread going to IKEA, because it’s heartbreaking to me to see these young couples shopping together to realize the aspiration of their future lives together with this junk they bring home.

I walk a lot. One of my great fascinations is all the stuff you see sitting out on the curb. I always tell my wife, when she’s thinking about buying something, “Squint your eyes and ask yourself, ‘Can I visualize it in a garage sale?’ If you can, don’t get it.”

My mom had one suit, a tweed ensemble she bought from I. Magnin, the department store. Because that’s what she could afford. Not a load of shit from Forever 21, the sort of plethora of just impossibly awful garments that people buy almost simply to buy them, to have the experience of shopping.

So what makes someone use something over and over? Is it just about the quality of its production?

RP: Maybe a sort of sentimental attachment? I have to do my best not to wear the same jacket every day. I have a bunch of jackets, but I really love this particular Dickies jacket I’ve had since I was 17. There’s no real reason for me to keep it except sentimental value.

PS: I don’t agree with that. I mean, sure, it’s got sentimental value. But I don’t agree there’s no other reason.

What’s your thesis?

PS: Well, there’s all kinds of social pressures. I mean that everything has meaning within its context.

So there are two things we’re talking about here: One is the relationship the user has with an object, which makes him keep returning to it, wearing the same jacket, whatever. And the other is the impression that it makes on other people. So what’s special about the Dickies jacket?

PS: That’s the one! If you could break it down into a reproducible formula, you know, everybody would do it! But that jacket has it.

Bohemianism is a reaction. It’s about wanting quality, of wanting something real. That’s what a lot of Memphis was about: finding something real. I later found out that most of the guys I was involved with over there in Milan were, you know, pretty upper-class kind of cats. Memphis was a reaction to Italian design of the time—the chrome and leather, which they took to be a very haute bourgeois banality.

So they were looking for something real, but that, ironically, was these postmodern synthetic laminates and veneers.

PS: Well, that was the current technology.

A lot of Memphis design is either somewhat contrary or hard to use. It was more about the style than about direct functionality. Neither of you make work according to ergonomic or economic efficiency.

RP: Sometimes I’ll do the opposite. I’ll make the drawers of the cabinets smaller, so you have to be more intentional with what you’re going to put inside there. I like the idea that it may force you to make a decision, rather than just filling it with clutter.Although ultimately it may just end up as a junk drawer.

PS: I love my junk. I have more junk than most.

Ryan, do you collect things?

RP: My collection is just art by friends. I’m lucky that most of what I have has some kind of story behind it. My favorite thing to do when anyone comes over is to talk about everything my pals have made.

Peter, I want to ask about your gear fetish and the stuff that you collect: the kitchen knives, the bikes, the canoes.

PS: It’s not a collection, it’s an amassing.

It’s a very good case study in the success of certain objects through time.

PS: There was a time when I was always very interested in the next thing. Then, I came to realize that the next thing isn’t really ahead of the old thing. I started to appreciate the value of the older technology.

Bicycles are a great example. The ones I’m really intrigued with are put together with what they call “lugs,” which offer an opportunity to create a decorative embellishment as well as a strength factor. These bikes really have a different feel. And that’s the question, right? When you hold one of my mugs, how does it feel? How does it feel when you use one of Ryan’s cabinets?

Is that only about ergonomics? Or is it something more imaginative, something more about the mind and the body together?

PS: Sure, that’s the spark. A lot of our engagement with objects is subliminal, so quick you don’t even think about it. It’s like wood versus plastic. How does it feel to touch? Is there an atavistic connection?

RP: You mix plastic as well as wood.

PS: Yeah, and that’s what Sottsass and company really loved: when materials were so gross, so low. The difference between a refined object and a coarse object. They claimed to love that brown line at the edge of laminate, where it’s glued.

What do you think is your most successful, enduring thing you made?

PS: The Bel Air chair definitely hit it. It’s an iconic image.

I got to know the photographer Julius Shulman before he died, and I went up to see him one day. He had these banners all over town advertising an exhibition of his work, featuring his famous photo of the Case Study House Number 22, with the girls with the petticoats sitting there.

He kept saying, in his thick Brooklyn accent, “You gotta have an iconic image!” I thought to myself, How can I tell him it’s a chair?

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.