Roughly a decade ago, I interviewed an engineer named David Winter about the trio of newly constructed hills on Governors Island. Today the hills, thick with vegetation, look like they’ve always been there. But they’re designer hills, conceived of by Adriaan Geuze, a founder of the Dutch firm West 8, and constructed from scratch on the southwestern shore of a designer island—one that was dramatically enlarged early in the 20th century—with dirt left over from excavation of the Lexington Avenue subway and dredge from the New York Harbor. These hills fascinate me because they’re 21st-century landforms, artificial constructs that we accept as nature.

Winter told me that, because the Governors Island shoreline couldn’t support a hill made from heavier materials like rocks and dirt, his team had to find something lighter. They initially considered Geofoam—“big blocks of Styrofoam,” as Winter put it, though the company swears they’re two distinct materials—but it was too light. “Hurricane Sandy came through while we were in the design phase,” he continued. “So we had to think: Would a hurricane blow the hill away?”

The idea of a hill so insubstantial that it could be launched by a hurricane altered my understanding of the world. I began to look more critically at the urbane interpretations of nature that have become a hallmark of early 21st-century design. I became aware that, lurking somewhere inside, say, Brooklyn Bridge Park’s expanses of greenery or the upsy-daisy landscape of Little Island, is a material resembling that of picnic coolers and boogie boards. But my concern was less about the possibility of flying hills and more about simple wear and tear. How long can this stuff possibly last?

“Since it is resistant to moisture and environmental damage, including insect infestation,” the Geofoam International LLC website says of its product, “its performance won’t be diminished over its long lifespan of approximately 100 years.” Predictably, this somewhat reassuring answer raises more questions. For one thing, Geofoam has only been used in the United States since the 1980s, initially in highway construction, so its longevity hasn’t been fully tested. And I know for a fact that using new building methods and materials can sometimes lead to unpleasant surprises. (Google “synthetic stucco” and you’ll see what I mean.)

But let’s say Geofoam really does last 100 years. Is that long enough? If not, what should the lifespan of a designed landscape be? The one I know best, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s Prospect Park, in Brooklyn, has been around for more than 150 years … meaning that, if its hills had been constructed of Geofoam, it might have already crumbled.

Of course, geologically speaking, a century or two is a brief existence. And non-designer landscapes—the natural kind, if human beings don’t interfere—can last an eternity. Kinder Baumgardner, a Houston–based managing principal at SWA, a large international firm mostly known for landscape design, has wrestled with this conundrum. “Everyone expects this stuff to be permanent,” Baumgardner says of his work. “That’s the heavy thing that we have to bear as landscape architects: everyone wants it to last forever.” But usually, it doesn’t.

Charles Birnbaum, founder of The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF), has long promoted landscape longevity. Prior to starting his organization, he spent 15 years at the National Park Service, where he authored the Secretary of the Interior’s Guidelines for the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes. The landscapes TCLF is most concerned with are of value not because they were the scenes of momentous events or had historically noteworthy owners, but because they’re important works of design.

Significant landscapes, however, rarely get the same respect as significant buildings. We seem to lose them more easily. I’m not talking about lightweight hills flying away. More often, Birnbaum says, we let them fall apart. “Landscapes are a whole lot less forgiving when it comes to deferred stewardship,” he says.

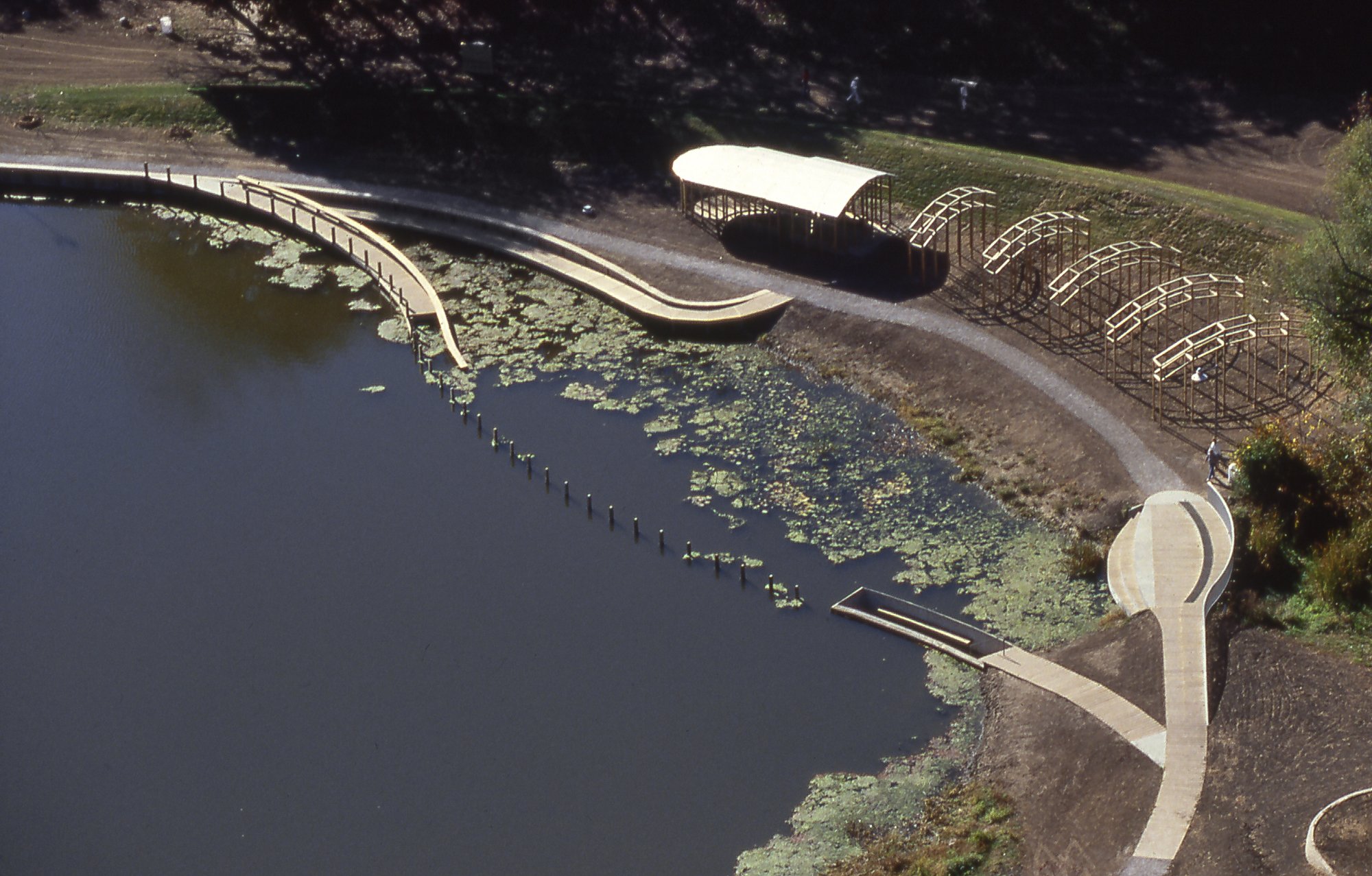

He’s referring to the impending destruction of an artwork by noted environmental artist Mary Miss called “Greenwood Pond: Double Site” (1989–1996), a supposedly permanent part of the Des Moines Art Center’s collection. The work, which connected Iowans to one of their remaining wetlands, was a precursor to the current generation of reinvented waterfronts. “Ninety percent of the wetlands in Iowa had been drained for farming,” Miss recently told me. “What if I could give [people] the direct experience of going into a wetland, and a sense of what lives and grows there?”

Her piece consists of a boardwalk that traces the water’s edge and dips down into a trough so that visitors can encounter the water at eye level. Created in collaboration with a local garden club, it became a template for the way Miss works today, tackling issues of resilience and sustainability through her non-profit City as Living Laboratory in conjunction with community members, scientists, and other artists.

In Des Moines, the museum’s director, Kelly Baum, says the piece requires $2.7 million in repairs—money it doesn’t have. “From what we can gather,” Birnbaum says, “they’ve done very little over the last nine years to take care of it. So now they’re blaming the artwork.” TCLF announced last month that Miss had filed suit in federal court to save the work. A judge in Des Moines has imposed a temporary restraining order, halting the demolition that was scheduled to commence on April 8.

While it’s unusual for a museum to destroy a work in its permanent collection, the loss of designed landscapes is beginning to feel all too commonplace. In New York City, we’ve lately dismantled two of them. First, there was the highly controversial 2019 decision by New York City’s Department of Design and Construction to bury the East River Park (opened in 1939, it almost made it to to 100) in eight feet of dirt, effectively transforming the entire park into one huge berm, intended to protect the neighborhoods directly inland from future storm surges.

And last year, Wagner Park, at the south end of Battery Park City—a grassy enclave designed by landscape architect Laurie Olin with Hanna/Olin, Lynden Miller, and Machado and Silvetti Associates—disappeared. The 3.5-acre oasis with stunning views of New York Harbor opened in 1996 and was demolished a mere 27 years later because, although it was designed to survive flooding, that’s no longer enough. “Now it’s been destroyed,” Birnbaum tells me, “because a park is now going to have to harden and protect lower Manhattan. There’s going to be these big gates and sea walls.”

So achieving that 100-year lifespan of a landscape, with Geofoam or otherwise, turns out to be quite difficult for modern humans. The natural world is falling apart all around us, largely by our own doing, and we have the hubris to think that we can find ways to replace it. But our needs and desires change too fast, and our attention spans are too short. Most of the work done by Baumgardner’s firm, he says, is “going to get torn out in ten years.”

However, as any visitor to the newly remade stretches of the Brooklyn and Queens waterfronts will attest, we’ve gotten very good at reinventing, or replicating, the natural landscapes that earlier generations methodically destroyed. We can conjure up salt marshes and rolling meadows that look like they might have during the millenia before the Europeans showed up. And these fabricated landscapes are not just there for pleasure, but to help mitigate the damage increasingly inflicted by un-designed nature, so-called acts of God.

But if this sleight of hand is to work, we need to invest in these fabricated landscapes, to build and maintain them as if they were culturally and historically significant. We need to take care of them as if we need them to last, not for a decade or even a century, but much longer. Because, practically speaking, we’ll only survive if we learn to think—now and then—in terms of forever.