A Pattern Language is about the size of a romance novel, but hardback, thick and dense, with 1,170 pages of thin-leaf paper and a distinctive yellow dust jacket. The cover features an ambiguous red circular emblem which, on close examination, appears to be the silhouette of three carpenters high up on a beam.

Its full title is A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction; the authors listed are Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa, and Murray Silverstein, with Max Jacobson, Ingrid Fiksdahl-King, and Shlomo Angel—though in common parlance, it is most always attributed solely to Alexander, who died in 2022. Its core idea, as stated on its dust-jacket flap, is that “people should design for themselves their own houses, streets, and communities […] and that most of the wonderful places in the world were not made by architects but by the people.”

First published in 1977, the book’s text is dense, with about 100 small black-and-white photos of notably bad quality accompanied by some diagrams. The pages are conventionally designed, but laid out with multiple typefaces: bold, italic, small caps. It is unlike most if not all other architecture books: It is not large-format (nothing coffee table here) and has no color photographs, almost no plans, sections, or elevations, and almost no known architects cited. There is no indication that the book emanates from Berkeley, California, the epicenter of countercultural U.S.A.

There is something encyclopedic-feeling about it, and also vaguely ecclesiastical, that reminds me of the Church of Ireland hymnal and psalter from my childhood. The book is complex, in its reception, its usage, and its underpinnings. Despite its simple and often poetic prose, it has had contradictory influences, being taken up by disparate fans from King Charles III to computer programmers and user interface designers. I applied its teachings to my Masters thesis, and in many ways, to my practice ever since.

I heard about A Pattern Language long before I saw the book, let alone read it. It was lurking in the background of my architecture education in University College Dublin, in the late 1980s and ’90s, mostly unspoken of, somehow oppositional, subversive. The “cool” professors, who swept across our department’s quadrangle in long black overcoats and round glasses, were Rationalists (“the Rats”), named for an earlier Italian mid-century movement, and showed us the buildings of Aldo Rossi, O.M. Ungers, and Josef Kleihues. When they did talk about Modernists, it was Louis Kahn, James Stirling, and post-modernists. They were, and are, deeply invested in and very serious about architecture at all levels: intellectual, historical, tectonic, and material, but not vernacular or at the scale of society.

I loved my architecture education, and it was very formative in many ways. But I had huge skepticism about how it related to the actual business of building and to the world at large, and I was looking for a way around what I perceived as an intellectual orthodoxy. That there was an architecture book that dissed, or upended, the gatekeeping of architectural design was very appealing to a disgruntled and disillusioned, idealistic young person.

The first section of the book explains how to use it, because, unusually, it is best read in a nonlinear manner. It features 253 patterns covering the built environment, from the scale of urban regions to towns, buildings, and ultimately furniture, trim, and door handles. Each pattern addresses a problem and proposes design solutions, drawn from existing built examples. The patterns cross-reference each other, so as a reader, one is quickly transferred to other pages, sometimes multiple other patterns at other scales.

For example: Let’s say I’m interested in putting a new deck on my house, so from the table of contents, I choose pattern #163, Outdoor Room, as that sounds nice. There is a smallish photo of a veranda-like room surrounded by dense lush foliage and mismatched comfy chairs, with Persian rugs on the floor. In a few pages, in beautiful prose, the need for an outdoor room is extolled, and then, in bold, are instructions for making such a place.

Short paragraphs at the beginning and end of the pattern refer to related patterns, including Common Areas at the Heart, Farmhouse Kitchen, Sequence of Sitting Spaces, Public Outdoor Room, Half-Hidden Garden, Private Terrace on the Street, and Sunny Place. And, just like that, I am flittering my way back and forth around the book, fingers acting as multiple pageholders, down rabbit holes and out again, as each of these patterns will refer to at least half a dozen others, in the state that we are now familiar with through hyperlinks and hashtags. This format allows for an individualized reading and branching accumulation of patterns, but also to a slight feeling of overwhelm, and a FOMO that somehow one missed an important pattern somewhere in the heat of pursuit.

Despite its prescient method of nonlinear use, and its reserved and arcane design, the book is very much of its moment, published after a decade of research centered in Berkeley, California, by Alexander and his team of other architects and a city planner. And so it follows on the civil rights movement, the questioning of authority, hippie idealism, alternative lifestyle, the counter culture in general, including a distrust of Modernist architects as the shapers of the built environment, and a desire to place the design of their spaces in the hands of the people. The irony is of course that the book was researched and written by professionally trained architects, to document their own failure as a profession!

According to the authors, Modern buildings fail to create human, beautiful, liveable environments, and vernacular building methods—buildings of the people by the people—are a way of making spaces that feel good and work well. The book, they write, offers “an entirely new approach to architecture, building, and planning, which will we hope replace existing ideas and practices entirely.”

These beliefs share some founding principles and ideology with Lloyd Kahn, who published Shelter, in 1973, just up the road from Berkeley in Bolinas, in Marin County; and the Whole Earth Catalog, published by Stewart Brand between 1968 and 1971 (and a couple of times after that), in the south Bay Area. All three provide an abundance of information in terms of examples, diagrams, photographs, products—everything one might need for the American agrarian movements of the 1960s and ’70s.

Alexander and Co.’s text could also be regarded as something like a cookbook—which was having its own countercultural moment at the time, including the Moosewood Cookbook (1974) and The Commune Cookbook (1972)—as recipes, or rules of thumb, are tried-and-true methods of getting to a known outcome. Cookbooks package and disseminate information, as well as encapsulate a cultural moment, an attitude toward food and health and hospitality, just like Alexander has embedded cultural ideas about what makes a good life at the various scales of building.

In other ways, Alexander could not have been more establishment. He was born in Vienna, grew up in England, studied chemistry and physics, then mathematics, and finally switched to architecture at Cambridge University, before getting a Ph.D. in architecture at Harvard. He then taught there and at M.I.T., and became professor of architecture at U.C. Berkeley.

He sought an objective, rigorous, even quantifiable way of creating beauty in the built environment. His methods were rigid, scientific, and prescriptive, especially in an earlier book, Notes on the Synthesis of Form (1964). By the time of A Pattern Language, and particularly its lesser known companion volume, The Timeless Way of Building (1979), Alexander had started to use less engineering and technical vocabulary, and instead wrote of the “quality without a name.” In various aphoristic, Zen-inflected and gnomic sentences he attempts to explain what this quality is: he tries “freedom from inner contradictions,” “alive,” “whole,” “comfortable,” “exact,” “egoless,” and “eternal,” but none of them satisfactorily capture the trait, so he returns to the quality as nameless (or the acronym QWAN, for short).

I used the idea of patterns in the Alexander sense when I was doing my Masters thesis at the National College of Art and Design, in Dublin—or at least that’s what I thought I was doing. I wanted to ask questions about craft, among them how craft uses the patterns of the past as a basis on which to create new forms. To quote myself: “The contemporary craftsperson is self-consciously using the unselfconscious patterns of tradition.”

Looking back on the work now, I am less certain that I fully understood Alexander’s work, but it served my purposes at the time. I was using an historical local chair type known as the Sligo chair as part of my thesis, and I was trying to distill the chair to its essence.

Here are drawings of historical Sligo chairs:

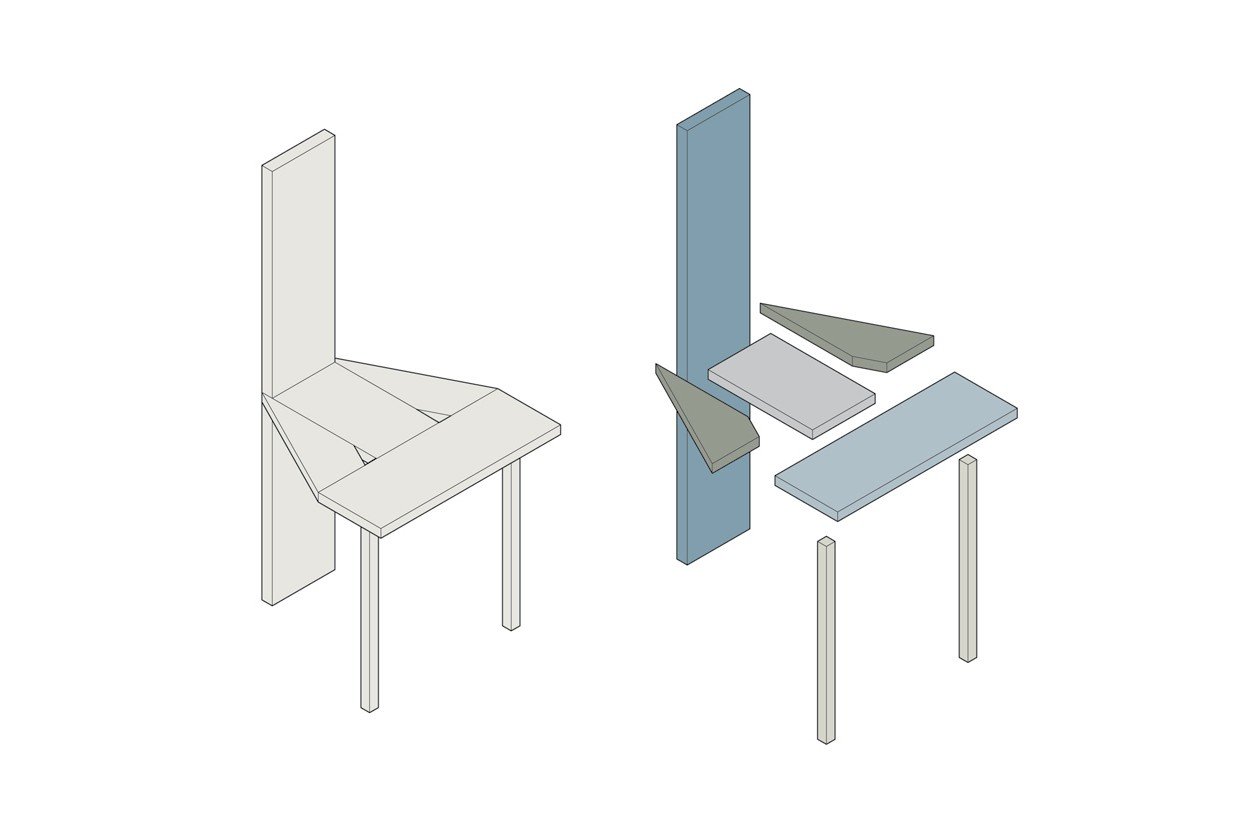

A breakdown of the simplest Sligo chair into components:

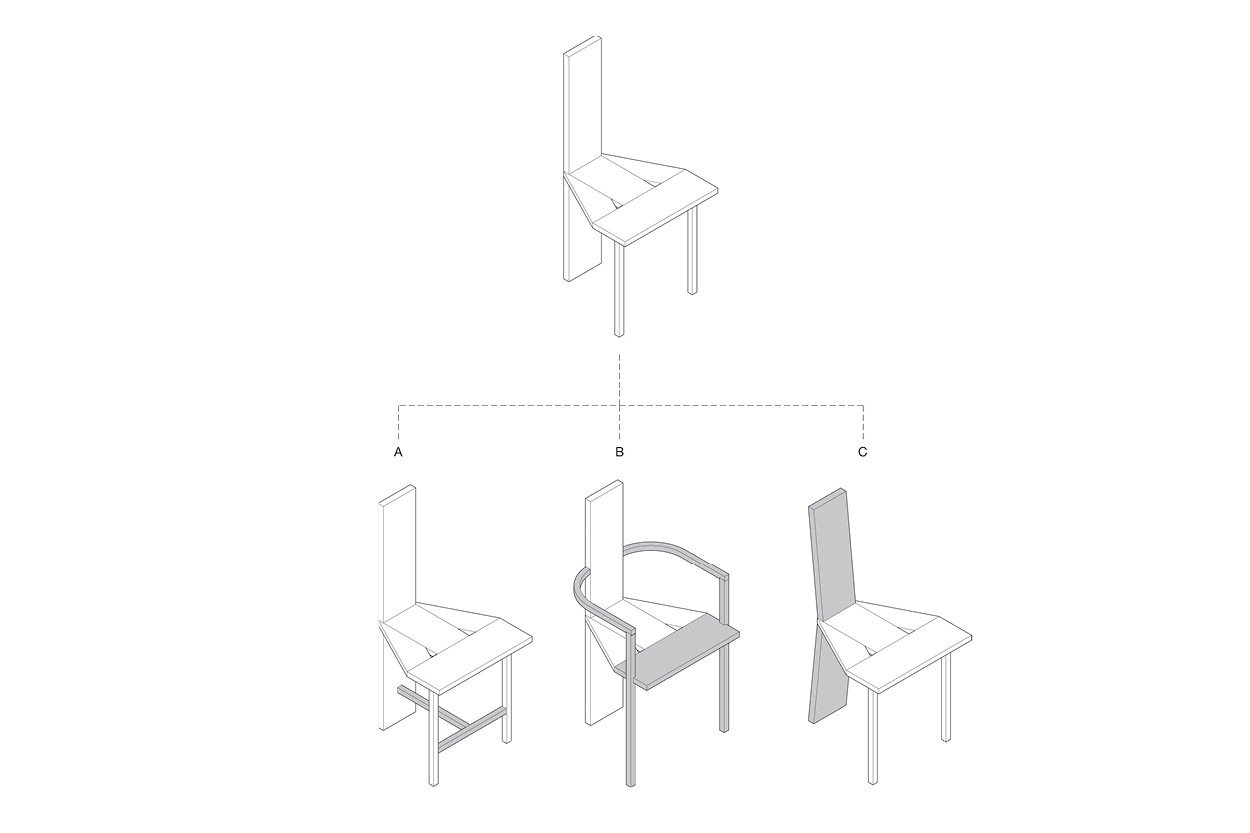

Other components added to historical Sligo chairs:

And my first rendition of a modern Sligo chair:

In retrospect, I might have been attempting to rationalize—or over-rationalize—my design methodology for the sake of a thesis in an academic setting. I have not used such a rigorous, or pseudo-rigorous, approach since. Perhaps my experience is not relevant, as the design problem is exceptionally small in scope compared to buildings. Yet the attempt to bring an archetype from the past into the present in a non-romanticizing, non-pastiche way is, I think, still valid.

Many designers would likely disagree. Alexander’s work has been taken up most enthusiastically in the computer science community, particularly in the field of software design and object-oriented programming, and perhaps least by architects themselves. Architects in particular are, in my experience, reluctant to assign qualities like beauty or timelessness to a building, and find the search intellectually distasteful, if not absurd. (I would note that in real life, I for one am much more likely to call something “beautiful” or “pleasing,” or the opposite, while being intellectually opposed to such definitions. This is possibly a hypocrisy of the professional adult world.)

It doesn’t help that Alexander’s own buildings, at least as depicted in photographs, are not inspiring in the least, do not convey the time-tested universality or beauty he sought, and will not be his legacy. His analysis of patterns in the built environment may work best when applied through metaphor or analogy, rather than directly.

But Alexander’s desire to devolve power outwards, to understand building as a group endeavor that is best understood through doing, is compelling. One anecdote encapsulates this: Alexander was being interviewed for a position as head of the architecture department at Cambridge University. The interview panel asked him who his first new hire would be, as a way of placing him within the various schools of thought in the academic architecture world. Alexander said he’d hire a carpenter. The panel objected: “No, no, no. Which named architect?” Alexander persisted. Annoyed, the panel obliged, and asked who he’d hire after the carpenter. ”A mason,” Alexander replied. He did not get the job. Such persistent pushing back on architectural orthodoxies, and focus on the reality of building as being at the core of the practice, is very appealing, and the world needs more of it.

In the end, Alexander’s work is important and influential precisely because of its complexities and inherent contradictions. It is simultaneously a toolbox for practical use, a romantic anti-Modern system for devolving power to people and thus control over their own lives, a methodological scientific rigorous theoretical framework for solving all kinds of problems at all scales, and a gnomic semi-spiritual search for eternal beauty.

It is easy to skim the book, to misunderstand. That allows it to be constantly reinterpreted in different contexts and by different people for their own purposes—therefore, perhaps unwittingly, preserving its relevance into the future.