In a postwar Vienna still reeling from the grip of fascism, the Austrian artist VALIE EXPORT gained international fame for staging confrontational works meant to address the lingering toxic masculinity in the city’s public spaces. For EXPORT—always rendered in capital letters; at 28, the artist changed her name in an act of radical autonomy, refusing both her father’s and former husband’s surnames in favor of the moniker of a popular brand of cigarettes—these provocative performances often meant situating herself in physically vulnerable positions.

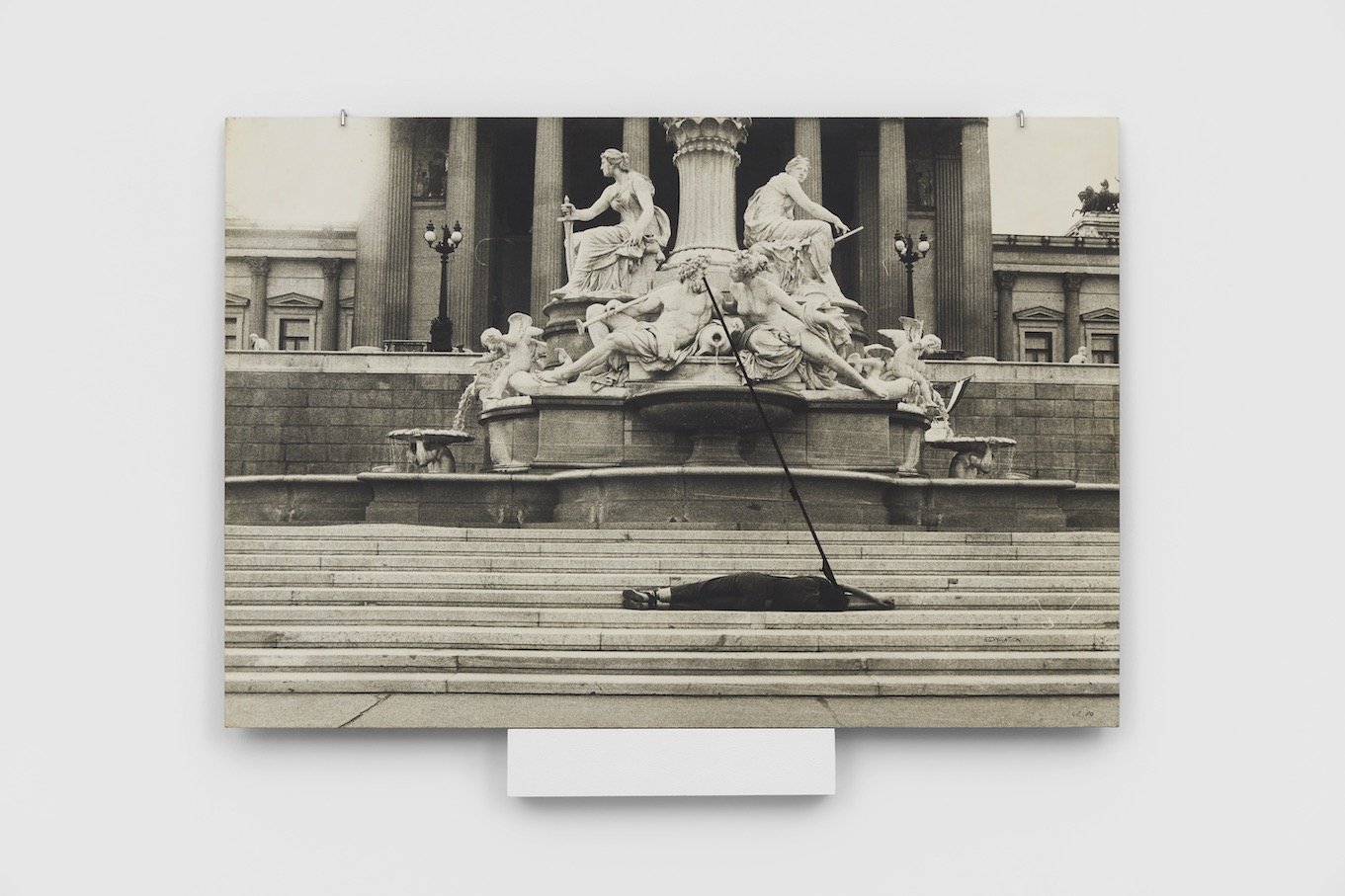

Consider “Body Configurations” (1972–1976), a series of photographic experiments EXPORT made in her thirties. She contorts herself into the urban landscape: crouched beside a steel bollard, inverted over a sidewalk vault, arranged midway down a set of marble steps as if she’d rolled to a stop there. While her body often appears lifeless or crumpled, it’s not submissive; the soft geometry of her posture is designed to specifically defy the rigidity that surrounds her. As The New York Times described the project two decades ago, during the artist’s first solo show in New York: “EXPORT seems to be haunting Vienna, inserting herself into places that are overpowering and by definition male. In the end her protest strikes the viewer as anything but passive.”

“Body Configurations” is currently back in the United States—a timely meditation as women are being forced to turn their bodies into a type of public square—with works from the series, including two of EXPORT’s films, exhibited at West Hollywood’s Schindler House, the California satellite of the MAK — Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, in a show called “VALIE EXPORT: Embodied” (through April 7), curated by the space’s director and curator, Jia Yi Gu. Complementing the photographic and cinematic pieces is a one-day performance program, slated for March 23, during which local artists will respond to EXPORT’s output, curated by Chloë Flores of the nomadic art organization homeLA.

“Her work is this strong, first-wave feminist political statement about gender inequality,” Flores says. “Inserting the female body into patriarchal structures—in this case, the urban planning and public spaces of Vienna—she creates these beautiful sculptural lines and curves with her body that brings forth what’s visible and not visible, and what’s present and absent.”

There is a way to view “Body Configurations” as a form of tactical urbanism, a woman’s body annotating the hostile gaps in the built environment. This disparity is particularly stark throughout the Los Angeles region, according to a pair of groundbreaking gender and mobility studies commissioned by Metro Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Department of Transportation in 2018 and 2019: Understanding How Women Travel and Changing Lanes.

Nationwide, women make up the majority of transit riders. This is also true in L.A.—although data from 2022, when all ridership dipped during the pandemic, shows those figures had been reduced to around half—where women transit riders are overwhelmingly low-income people of color. Women also make more trips as well as more complex trips, according to the studies, with dynamic care-giving and errand-running schedules that require them to reach multiple destinations during off-peak hours. Yet virtually every aspect of L.A.’s transportation infrastructure has been designed for the needs of the 9-to-5 office commuter, who has traditionally been whiter, more affluent, and male. (And who is, honestly, probably not even in the office anymore.)

In the studies, women riders expressed concerns about long wait times, physical peril, and dangerous walking conditions, all of which could be addressed with simple interventions such as more bus shelters, larger shade trees, brighter street lighting, and wider sidewalks that offer better protection from cars. But in L.A., these interventions rarely materialize as physical infrastructure. Such investments are not prioritized. That’s because, to the city, the pedestrians who use them are invisible.

Which is why it’s so important that EXPORT arranges herself in the gutter for “Einkreisung” (1976), named for the German word for “encirclement,” first exhibited at the 1980 Venice Biennale. Her face here is exposed but her eyes remain closed, her pose caryatid-like as she girds the curb, a female support structure holding together the entire city, even if doing so clearly might kill her.

The bright red U traced by her spine—EXPORT often annotated her gelatin prints with colors or graphics—echoes a traffic-safety intervention known as “daylighting,” in which a curb is painted red at a place where people cross, in order to make pedestrians more visible to drivers. In my day-to-day life, as a woman trying to keep my own family alive as I move them around L.A., that blood-red curb represents the thinnest buffer between my children and a speeding driver, the place where I hold my breath as I hold their hands, stepping into the void.

While EXPORT was producing “Body Configurations” in Vienna, Dutch parents were laying their own bodies down in the streets. Led by a young mother, Maartje van Putten, who was later elected to European Parliament, the action group Stop de Kindermoord—literally “stop the child murder”—staged demonstrations to protest the growing numbers of kids killed by what had become an increasingly driver-centric postwar society. Bit by bit, leaders carved out car-free space in their cities and funded safer ways of getting around. Deaths plummeted.

The U.S. is trending in the opposite direction. Each year, a “dying-in” is held here in L.A., where traffic fatalities have risen for the third year in a row, despite a citywide goal of zero deaths by 2025. This year, 330 volunteers were needed to visualize the number of deaths in 2023, the highest in two decades, nearly one person killed per day on the city’s streets. It is a statistic that feels abstract until you see family members silently holding up photos of their children as they lie among the white roses and votive candles, 330 bodies draped across the cold marble steps of City Hall.

If our paths through the city are not made visible, can we really be protected? One spring morning, before dawn, I was invited to observe the work of Crosswalk Collective LA, a group of anonymous volunteers who paint crosswalks in the city’s dangerous unmarked intersections. To watch the collective in action is like municipal-services performance art, with headlights bouncing off neon reflective vests in the darkness, silence except for the wet slaps of paint rollers.

In order to lay down their stripes, the collective must also simultaneously direct traffic around themselves: They hold a sign that reads STOP and trace over a stencil that reads STOP, their bodies protecting other bodies. Many of the crosswalk requests prioritized by the collective come from frustrated parents who have begged the city for safer pedestrian infrastructure around their schools. The transportation department sometimes takes the hint and formalizes the crossing, but more often buffs out the collective’s work, returning the street to its blank state.

Recently, the collective has turned its attention to the plastic bollards the city sometimes uses to create what are called curb extensions, where a few more feet of asphalt is painted to demarcate extra crosswalk-adjacent road space for pedestrians. This is, of course, only a mere suggestion, as drivers can flatten the flimsy poles as easily as they can flatten the pedestrians they are meant to protect.

In one video posted by the collective, a garden gloved–hand fills the yellow tube of the bollard with rocks, then adds soil, then gently tops it with a succulent. Beyond fortifying the bollard—which it does, a little—the action draws attention to L.A.’s lopsided traffic safety policies. The city’s financial workers have metal bollards installed outside their banks, while elementary school students get the infrastructural equivalent of a Wiffle bat.

The rest of the city’s pedestrian infrastructure is similarly broken. The same year I began pushing a stroller over L.A.’s sidewalks—40 percent of which are estimated to be in need of repair—the largest class action lawsuit in the country was filed on behalf of 280,000 disabled Angelenos who could not navigate them. In 2015, a $1.4 billion settlement to repair the sidewalk network, including installing new, ADA-compliant curb ramps at intersections, was lauded as heralding a new era for the city’s pedestrians. But six years later, only one percent of the city’s sidewalks had been fixed, with a backlog of 50,000 requests. Resources aren’t necessarily the issue: City data confirms that pothole requests for the roadways where cars drive are usually fixed within a week.

L.A. artist Fiona Connor spent two years piecing together “Continuous Sidewalk” (2023), which shows just how far the city has to go. After giving up her car during the pandemic, Connor reproduced 23 sections of Downtown L.A.’s sidewalks, which she assembled like a concrete patchwork quilt in her studio. (She couldn’t install it in the gallery that exhibited her work because it would have been structurally unsafe to introduce what is effectively a new floor to the 10th-floor space.)

In the piece, the very worst sidewalks to navigate become the most aesthetically compelling: ruptures smoothed with chunky asphalt patches, crumbling utility covers threaded with tiny rebar skeletons, brick seams running through cracked concrete like a mineral deposit, the diagonal accents of bright red curbs. “When you imagine a city, you don’t imagine it as a linear path,” Connor told the Los Angeles Times. “It’s a cacophony of different moments.” Despite the irresistible allure of Connor’s graffitied and gum-dotted panels, the project reveals a profound civic neglect; cacophony is exactly what we don’t want underfoot.

It’s important to remember that L.A.’s pedestrian paths were once, in fact, linear. One of my favorite Instagram accounts, @stampedsidewalks, posts photos of the information that contractors stamped into the city’s wet concrete slabs as they dried. These stamps consist of a name, sometimes a company, and usually a year, arranged into a tidy and utilitarian wordmark: Boock Bros., E. Schelling, C.W. Sparks. (In the pre-internet era, the stamps provided free advertising for the services rendered but were sometimes required by the city to assure accountability.)

Each stamp posted includes a mini-biography of the contractor, and I’ve come to root for some recurring characters as they compete for sewer-line and street-lighting jobs. These contractors not only built the sidewalks, they also built the local schools and surrounding blocks of Craftsman bungalows, a vast, smooth pedestrian network that existed long before the cars arrived.

But what’s most alarming about these dates pressed into concrete is how many of them are more than a century old. As I walk my kids to school over pavement jackknifed by ficus roots, I think about the time when the stamps were fresh. Perhaps, instead of waiting months (or years) for a response to a 311 request, a quick inquiry to Fairchild Gilmore Wilton Co. might have resulted in an immediate repair.

And perhaps the proposed fix would be better than the city’s current strategy, which is this: If sidewalk is damaged by tree roots, and the sidewalk is eventually repaired, the offending tree is often simply cut down. Last year, a judge ruled that the city’s plan to remove 13,000 mature trees in order to repair sidewalks failed to consider the benefits of those trees to pedestrians, forcing L.A. to forge a still-to-be-determined strategy for saving trees, fixing sidewalks, and guaranteeing freedom of movement for the Angelenos who rely on both.

EXPORT’s work shows one way forward. The celebrated modernist residence of Austrian-born American architect R.M. Schindler, the one that houses the MAK Center, sits behind a screen of bamboo on a quiet residential street in West Hollywood, a 1.9-square-mile city surrounded by L.A. It is an ideal location from which to view “Body Configurations” for many reasons, particularly for the opportunity to see EXPORT’s work juxtaposed against the home’s concrete walls, the ultimate urban canvas.

When I ride the bus there from my house—off-peak waits average 20 minutes, with no bus shelters at either end—it deposits me a few blocks away but still in L.A., giving me a chance to participate in one of my favorite pastimes: tracking the transition in the built environment from a city that has tried to pretend walking doesn’t exist, into one that has enshrined pedestrian paths into physical monuments.

As I cross West Hollywood’s city limits, the change in sidewalk quality is instantaneous. I immediately think to myself that Fiona Connor would have a difficult time here finding panels cacophonous enough to reproduce.

But it’s not just the sidewalks that are different. Just outside the Schindler House, I’m stopped in my tracks by a large, glossy-leafed oak tree fitted with a bright yellow crutch. It’s anchored and bolted to the ground in the tangle of roots, cradling a limb like a giant compass, a triangle of support offered and accepted. The sidewalk, instead of unsuccessfully continuing over the ground where the roots have surfaced, jaunts casually into the street, then resumes its original path.

The entire intervention—known in sidewalk terminology as a “meander”—occupies exactly one parking space. In one elegant move, roadway is reclaimed from cars, a tree is saved, shade is preserved, and the pedestrian’s route is never interrupted. Encircling it all, like a sassy hip thrust, is a bulbous, bright red curb: what a city looks like when it truly sees its walkers.